Chinese Power Plant Develops Advanced Coal Technology

China’s clean energy ambitions.

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

TIANJIN, China—Though Chinese workers this week celebrated the 61st anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, a holiday season as significant as July 4 in the United States, a swarm of construction laborers at China’s GreenGen coal-fired gasification power plant were busy welding pipes, fitting massive joints and bending steel for forms to be filled with concrete.

Since construction on the $1 billion project began in June 2009, said Li Liangshi, the deputy chief engineer, the dusty construction site has been a nonstop 24/7 hive of activity for 2,100 workers. Next year, the consortium of companies financing the project — five of them Chinese, plus Peabody Energy, the world’s largest private-sector coal company — plan to start operations.

GreenGen’s principle purpose is demonstrating advanced Chinese technology to burn coal much more efficiently than conventional power plants, and to prove that its climate-changing carbon emissions can be safely stored deep underground, said Deborah Seligsohn, the principal advisor of the World Resources Institute’s China Climate and Energy Program, who joined a tour of the plant on Thursday. Another of its innovations is the plant’s cooling system, which will use seawater instead of fresh water.

“China has a lot of coal,” Seligsohn said. “This project deals with efficiency and pollution abatement in a fairly clean way.”

Outside Stalled Negotiations, Promising Steps

This week the U.N. climate negotiations inside the expansive Meijiang Convention and Exhibition Center were stymied, in large part by a dispute between China and the United States over which country is doing enough to combat climate change. But outside the closed negotiating sessions, a series of side events, convened by NGOs and governments, have described in detail the progress China is making to advance clean technology and energy efficiency, which are intended to simultaneously build economic vibrancy while lowering carbon emissions.

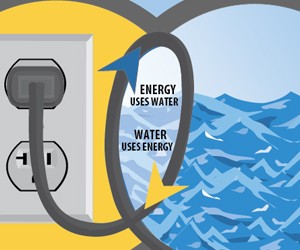

The effect of those new energy technologies is also to address the gathering momentum of a tightening choke point between rising energy demand and diminishing supplies of fresh water that threaten to bring China’s economic growth to a standstill.

China, the world’s third driest country, has roughly 163 trillion gallons of water available for all uses, according to a study released in December 2009 by McKinsey’s 2030 Water Resources Group. About 63 percent is used by farmers, down from 85 percent in 1980, according to China’s Water Ministry. Municipal and domestic use has been stable at around 12 percent, and industry uses 23 percent — 80 percent of which is used to operate and cool China’s 10,000 coal-burning generating units at 550 power plants.

Water-Energy Choke Point

But by 2030, according to the McKinsey study, the demand for water in China’s rapidly growing economy will reach 215 trillion gallons, 52 trillion gallons more than is available. The increase in coal production and consumption accounts for most of the increase. The amount of water consumed by China’s energy sector will reach 70 trillion gallons, or 32 percent, while agriculture’s share will fall to 51 percent, according to McKinsey.

In part because of its concerns about freshwater supply, China’s government and its manufacturing sector have embraced wind power and solar photovoltaic energy, neither of which uses much water in manufacturing or energy production. In 2005 the government passed a renewable energy standard requiring 10 percent of the nation’s power to be generated from alternative sources by the end of this year. It also backed the standard with public financing to assist developers in tapping new business.

From a slow start a decade ago, Chinese wind and solar manufacturers have rapidly developed the national solar and wind markets into the world’s largest, said Steve Sawyer, the secretary general of the Global Wind Energy Council. China now produces 26,000 megawatts from the wind, second only to the 35,000 megawatts that wind generates in the United States.

China is devoting just as much attention to modernizing its coal-fired energy production and reconsidering how much water that sector uses. China recently built and opened the Shenhua Direct Coal Liquefaction plant in Ordos, Inner Mongolia, in the north central region, a first-of-its-kind facility that employs a Chinese-developed technology to convert 6,000 tons of coal a day into more than 1 million tons of liquid fuels per year, according to the World Resources Institute. The plant, paid by Shenhua, the country’s largest coal company, will also be one of the largest point sources of carbon dioxide in the world.

Though Chinese engineers are experimenting with tools and equipment to dispose of some of the plant’s carbon emissions underground, the government has grown alarmed at how much water it takes to operate. The program to build more such plants has been curtailed, said Jennifer Turner, director of the China Environment Forum at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C.

The need to develop more efficient ways to use coal, and to lower requirements for water, is keener in China than any other nation. China’s economic development agency projects the demand for coal will reach 3.15 billion tons this year, more than three times production in the United States. More than 70 percent of all of China’s energy is produced by coal, and the government forecasts the demand for coal will rise over the next decade to more than 4 billion tons annually.

China To Develop Advanced Coal

Meanwhile, coal’s influence on climate change, which is steadily diminishing the country’s freshwater reserves, is significant. In China, coal accounts for most of the 6.3 billion tons of carbon emissions, nearly 10 percent more than the United States produces, and about a quarter of all the climate-changing emissions globally.

In sum, China and its utilities and manufacturers see the need to reduce coal’s influence on global warming and freshwater scarcity, and an opportunity to build economic strength in reaching that goal.

Here in Tianjin, the GreenGen project is at the head of a pack of Chinese power plants designed to burn coal more efficiently, use less water, and develop and prove carbon capture and storage (CCS) techniques. China has built more than 20 supercritical and ultra-supercritical power plants that operate at extremely high water temperatures and pressures, and use half the water of a conventional coal-fired plant, said Fuqiang Yang, a scientist and director of Global Climate Change Solutions for WWF-International’s office in Beijing. They do so, Yang said, by producing much higher efficiencies, generating more power with less coal, and thus lowering water consumption, as well as emissions per megawatt of power generated.

According to the World Resources Institute, China has developed and approved a number of new energy projects to demonstrate more efficient energy generating and pollution control practices. They include the 845-megawatt Huaneng Gaobeidian Co-Generation plant in Beijing, the first in China to fully test carbon dioxide capture and feature a full suite of environmental controls. During winter months, steam from the plant is used for district heating, and efficiency can be as high as 84 percent. Engineers estimate the plant uses about 400,000 tons less coal annually, and thus less water, than a similarly-sized conventional plant.

GreenGen Could Be Big Advance

GreenGen represents the next step in China’s drive for higher efficiency and lower pollution in generating power from coal. When the first of three phases opens next year, GreenGen will be the first utility-scale IGCC power plant in China, and one of the few operating in the world.

When fully operational in 2014, Chinese officials say, GreenGen will generate 650 megawatts at 60 percent to 80 percent efficiency—about twice the efficiency of conventional coal-fired power plants—and dispose of its climate-changing emissions through CCS technology. Some of the emissions will be pumped into wells and used to increase oil production in one of China’s older oil fields, which is close by.

If the plant is a success, said Jiang Kejun, a director of research for the Energy Research Institute, a unit of the National Development and Reform Commission, China is prepared to build 20 more such gasification and CCS power plants. “We want to make sure it works,” he said.

Keith Schneider is Circle of Blue’s senior editor. Contact Keith Schneider

Read more about the United Nations’ first climate conference in China on Circle of Blue.

Connor Bebb assists in daily operations, aids in research, oversees social media outlets and develops social media strategies at Circle of Blue.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!