Karoo Uranium, Fossil Energy Development Defies Water Scarcity and Reason

Renewable energy flourishes while South Africa leadership pursues risky, costly conventional fuels path.

It is fitting that the Karoo, a spectacle of light and land so central to South Africa’s geography and history, is now the stage for another of the momentous choices about energy confronting the nation at the bottom of the continent. Photo © Keith Schneider / Circle of Blue

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

GRAAFF-REINET, South Africa-– A contentious idea to use billions of gallons of scarce water to develop natural gas brought Stefan Cramer, a respected German-trained groundwater scientist, to settle in a 19th-century cottage with stucco walls and a reed and mud roof near the center of South Africa’s desert Karoo.

A well-regarded hydrogeologist with decades of experience in some of the world’s important oil and gas fields, Cramer was dispatched to the Karoo two years ago by the Southern African Faith Communities Environment Institute. His assignment: add scientific rigor to the Cape Town-based organization’s campaign to block fracking in a spectacular landscape of eroding basalt and unrelenting sun.

Map © Codi Kozacek / Circle of Blue

For a brief few years, largely as the result of a 2011 U.S. government estimate of potential reserves, South Africa entertained the idea that the 450,000 square-kilometer (174,000 square miles) Karoo might become a world-class natural gas field. Cramer, who is 64 years old and lives in this historic and lovely Afrikaans desert town with his wife, Erika, did not need to do much to help dispel South Africa’s flirtation with shale gas.

Though SAFCEI and other groups remain vigilant, fracking the Karoo is an idea that is slipping away. It has been more than a year since Royal Dutch Shell dropped its program to frack the South African desert. Plunging fuel prices, the complete absence of an expensive pipeline transport network, scarce water, faint understanding of the Karoo’s deep geology, and fierce public opposition has turned the South Africa Department of Energy’s fracking division into a quiet repository for an approach to fossil fuel production that is unfit for its place and time.

It is another improbable energy pursuit, though, that Cramer tripped over last year that keeps him grounded here. South Africa, which has operated the 1,800-megawatt seawater-cooled Koeberg nuclear plant along the Atlantic Ocean coast near Cape Town since 1984, wants to build six new nuclear power plants. Its senior leaders see in the Karoo’s billion-year-old geology, expansive valleys, and table-top summits fertile territory for supplying uranium, and perhaps hosting a new uranium enrichment plant.

“We were taken by surprise when we accidentally learned how far the uranium exploration had progressed in the absence of any public debate,” Cramer explained. “Perhaps because of the public perception that fracking was such a huge threat, activists and scientists simply overlooked the potentially much wider and more damaging threat emanating from uranium mining. We have been on this topic only since August 2015, when we attended an information session by the mining company.”

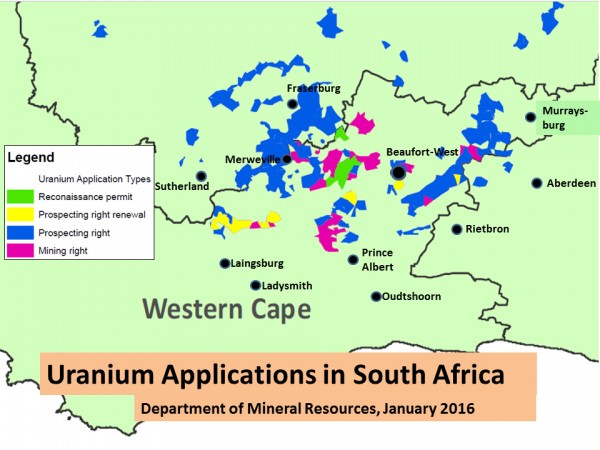

Peninsula Energy, an Australian mining company backed by Russian financiers, has gained control of 750,000 hectares (1.85 million acres) of desert and grazing lands for mining. Cramer calculates that uranium development will consume 1.3 million cubic meters (343 million gallons) of water annually. Like all of the canvas of color and the banquet of quiet that is the Karoo, the region 200 kilometers (125 miles) west of here, around Beaufort West where much of the development is centered, has meager existing water reserves.

“We were taken by surprise,” said Stefan Cramer, a well-regarded hydrogeologist. “Perhaps because of the public perception that fracking was such a huge threat, activists and scientists simply overlooked the potentially much wider and more damaging threat from uranium mining. We have been on this topic only since August 2015 when we attended an information session by the mining company.” Photo © Keith Schneider / Circle of Blue

“The Apartheid government closed mining and uranium enrichment in 1992 before the black government came to power,” said Cramer in an interview with Circle of Blue. “South Africa now plans to restart the entire nuclear cycle. That includes mining, uranium enrichment, and power generation. First it’s using millions of cubic meters of water to frack shale gas in the Karoo. Now it’s millions of cubic meters for uranium. None of it makes sense to me.”

Cramer is a tall, sturdy, bearded scientist whose public interest instincts are keen. His manner, welcoming and direct, is much like the 230-year-old Dutch-style high desert town that, because of him and his wife, has become a center of anti-uranium research and organizing. Opposition headquarters is a cool and airy cottage with a glorious garden that rests in the lee of Sneeuberg Mountain.

The irony of South Africa, certainly the irrational feature of South Africa’s headlong pursuit of risky gas and uranium reserves, argues Cramer, is that the Karoo also hosts one of the world’s most fruitful new wind and solar energy sectors.

Map courtesy South Africa Department of Mineral Resources

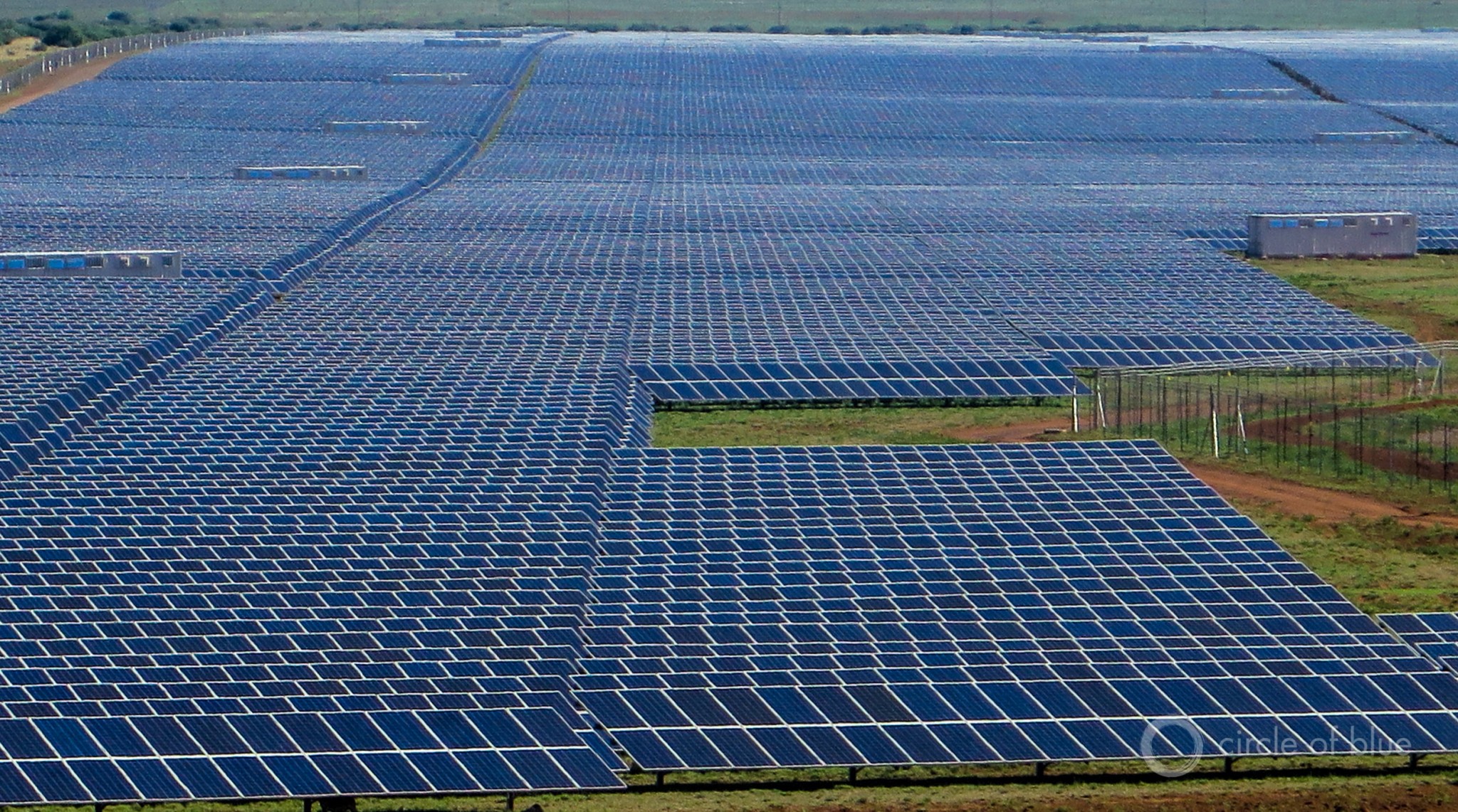

Wind farms are tucked into mountain passes and spread across open desert in all three Cape provinces that form the Karoo. A solar corridor has opened in Northern Cape province. In the desert between Kimberley and Postmasburg, in a dry valley surrounded by low hills, SolarReserve opened the 96-megawatt Jasper solar photovoltaic power station and its sister 75-megawatt Lesedi solar station in 2014 at a cost of nearly $US 500 million. The expanse of electricity generating panels installed by the Santa Monica, California-based company reflects the sun and the sky, and is so large that from a distance both stations look like shimmering blue lakes.

“South Africa put the right people in charge of its renewable development. The program has good management and it’s working,” said Kevin Smith, the chief executive of SolarReserve, which is scheduled to start construction of a 100-megawatt, $US 750 million concentrating solar station with energy storage capacity at the same desert site later this year. “They are conscientious and they want the program to be successful.”

Magic and Import of the Karoo

There is not a better place to ascend South Africa’s mountains of clean energy production and descend its unfaltering slopes of ill-conceived fossil and uranium energy convention than the magnificent Karoo. Encircling a third of South Africa’s geography, the desert starts in the east close to the mountains of Lesotho, heads north nearly to Johannesburg, reaches south almost to Cape Town, and west to within 100 kilometers (62 miles) of the Atlantic Ocean.

Millions of years ago the Karoo was the bottom of a teeming sea. Over the last 170 years herds of cattle and flocks of sheep grazed its grasses and woody desert shrubs, and trampled the thin and rocky soils. Here and there hard rock mines opened to exploit underground mineral seams.

Thinly populated, with towns hours distant from one another, the Karoo’s hot desert extends to the sides of mammoth tabletop ridges that turn purple at dusk. This canvas of color and light, of rock and mountain and glorious sunsets, has inspired generations of South African poets and artists. Photo © Keith Schneider / Circle of Blue

Thinly populated, with towns hours distant from one another, the Karoo’s hot desert extends to the sides of mammoth tabletop ridges that turn purple at dusk. This canvas of color and light, of rock and mountain and glorious sunsets has inspired generations of South African poets and artists.

Its seared ground, relentless sun, and temperatures that can change 25 degrees Celsius (45 degrees Fahrenheit) from day to night have driven countless Karoo settlers to despair. The ageless desert has been called the ruinous landscape between heaven and hell.

It is fitting that such a region so central to South Africa’s geography and history is now the stage for another of the momentous choices about energy and the economy that confront the nation at the bottom of the continent. If facts and outcomes were the sole factors, the choice would seem straightforward.

Clean Energy Works

Since construction started in 2012, 13 wind power plants and 31 solar generating stations have opened in South Africa. They generate nearly 2,300 megawatts of electrical capacity, according to the most recent published tally by the South Africa Department of Energy. To date, $US 6 billion has been invested in South African clean energy. The Karoo hosts nearly three quarters of the renewable plants constructed so far.

Another 45 sizable wind and solar plants are in various stages of construction, financing, and permitting in the Karoo and nationally. A new round of government bids for building renewable energy plants, the fifth since 2011, is expected to begin later this year.

South Africa’s renewable sector is putting 1,000 new megawatts of generating capacity online annually, according to the Department of Energy. Plants are being built in 24 to 30 months on average, and coming online on schedule and close to budget. The country appears well on the way to reaching the national target of 6,000 new megawatts of renewable generating capacity by 2020, and 18,000 by 2030. No South Africa industrial infrastructure project in the 21st century has come close to this level of achievement.

A solar corridor has opened in Northern Cape province. In a dry valley surrounded by low hills near Postmasburg, Chinese solar panels unloaded from a ship in Port Elizabeth arrive at SolarReserve’s 96-megawatt Jasper solar photovoltaic power station. Photo © Keith Schneider / Circle of Blue

One of the primary reasons is that none of the new plants, according to government summaries, come with the inordinate expense, technical challenges, severe environmental damage, and fierce public resistance that are the proven consequences of developing conventional sources of energy in South Africa.

The issue raised in the Karoo, and in academic circles across South Africa, is why, despite the glittering achievement of wind and solar development, senior government leaders are so intent on devoting the majority of government capital and focus to old and polluting fuel sources?

The answer is not forthcoming from the Department of Energy. As with all South Africa agencies, the agency declares openness and transparency as vital operational values. But like all but one South Africa department encountered in Circle of Blue’s Choke Point: South Africa project, the Department of Energy’s senior officers declined repeated requests to be interviewed for this article.

Kevin Smith, though, offers an explanation.

“They are not so different than a lot of countries,” said Smith, who is developing SolarReserve’s concentrated solar generating plants around the world. “If you talk to the utility side of the market in the United States, not all, but a number of executives consider renewable energy to be a flash in the pan. They don’t see it as an economically sustainable model. They are more comfortable sticking to the model they are comfortable working with – large gas and coal facilities. Meanwhile there is a burgeoning global renewable market. The fossil guys view it as a strange younger brother.”

If familiarity, and not actual performance, helps explain South Africa’s reluctance to shift more aggressively from conventional fuels to renewable energy, then at least part of the reason may be found in psychology. Cognitive psychologists seek to predict a person’s motive, or a nation’s pursuit of its goals, with the “theory of planned behavior.” The central tenet is to understand and forecast human motivation, which is principally driven by a person’s expectation that the outcome will be successful.

The expanse of electricity generating panels at the Jasper solar photovoltaic power station in the Northern Cape reflects the sun and the sky, and is so large that from a distance it looks like shimmering blue lake. Photo © Keith Schneider / Circle of Blue

South Africa’s planned behavior following the end of Apartheid in 1994 was to build a society of freedom, mobility, and prosperity for all. Essential to that vision was the recognition that South Africa’s economy needed to be rebooted to reflect the economic turmoil and dire ecological conditions developing in the 21st century. By the time South Africa elected Thabo Mbeki as its second black president in 1999, academics and government authorities recognized that a good deal of the country’s success depended on replacing the dirty coal-fired power sector with a much cleaner energy supply.

Under the Mbeki government, South Africa published a stream of formal 21st-century national strategies that laid out the steps to shift the energy industry away from coal, conserve water, restore rivers, reclaim contaminated land, and invite advanced technologies. The documents were meant to form the foundation of a new South Africa that would employ hundreds of thousands of people in productive jobs, and be recognized at the forefront of the world’s most sustainable and technically savvy nations.

The Karoo encompassed a fair measure of that vision. The desert’s isolation and seismic stability, for instance, compelled South Africa to build KAT-7, one of the world’s most advanced radio telescopes. The universe-scanning instrument helped South Africa become the designated site for the much larger $US 1.1 billion Square Kilometer Array, planned as one of the most advanced scientific instruments on Earth, that is under development and being financed by South Africa and nine other nations.

Trail of Dismay With Coal Power

Planned behavior, however, comes undone when external factors blow up the best intentions. The result is a cognitive crisis, like the sort now unfolding across the Karoo and almost all of South Africa.

In Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces, South Africa is years and billions of dollars away from completing two mammoth 4,800-megawatt coal-fired power plants, Kusile and Medupi, that are draining the national treasury and may not have sufficient water to operate at full capacity when they are finished, perhaps in the early 2020s.

In KwaZulu-Natal province, which borders the Indian Ocean, citizens and some of the country’s most influential environmental organizations are battling the government’s effort to open new coal mines and start construction of a new coal-fired power plant, arguing that they are too dirty and not needed.

A wildebeest grazes in a broad valley west of Graaff-Reinet in the Eastern Cape. Photo © Keith Schneider / Circle of Blue

Because of climate change, South Africa’s hydrological cycles have been disrupted. The country, one of the world’s driest, is getting still drier. A deep drought, now in its second year, is battering South Africa’s farm and energy sectors. But the country’s allegiance to its coal mining and coal combustion industries produces more climate changing gases than all but 13 other nations.

Such details do not bear nearly enough consequence for President Jacob Zuma, whose son owns a significant portion of one of South Africa’s largest coal mines, and whose African National Congress party has held financial interests in two coal-fired power stations.

Last August, Eskom, South Africa’s government-owned utility, started commercial operations at the first 794-megawatt generating unit at the coal-fired Medupi power plant. President Zuma spoke at the opening, praising the big new plant and emphasizing the need to meet the country’s demand for electricity.

“The energy shortage is a serious obstacle to growth,” said Zuma. “In this regard, the opening of Unit 6 is a significant achievement for the country.”

But three months later, in a speech at the G20 gathering of heads of state in Turkey, Zuma could not remember how much money is being invested to develop the first 6,000 megawatts of renewable energy in South Africa, more than eight times as much generating capacity as Medupi’s single operating unit. He told the meeting it was $US 14 million. The accurate amount is $US 13.4 billion.

The Orange River, drained by a deep drought, is one of the Karoo’s primary sources of fresh water. Much of the river’s water is devoted to desert agriculture. Photo © Keith Schneider / Circle of Blue

“We have a model of supplying electricity with coal that pollutes, causes climate change, and is so outdated it is hurting our development,” said Saliem Fakir, a renewable energy specialist at the Worldwide Fund For Nature office in Cape Town. “We have another model to supply energy with wind and solar power that is producing just the opposite results. It’s clean. Doesn’t add to climate change. It uses almost no water, and it’s working. But we aren’t moving nearly as fast as we need to in that direction.”

“What’s happening in this country on energy does not make a lot of sense to me,” added Stefan Cramer, in an interview with Circle of Blue. “There are places where mining is reasonable and where it isn’t. Mining uranium in the Karoo should be off limits.”

Uranium Mining in Play

The Department of Mineral Resources is close to evaluating Peninsula Energy’s applications to mine uranium in the Karoo. The applications have galvanized environmental groups and Karoo residents to file petitions of appeal and court cases to halt the government reviews.

Though South African leaders have called for building six new reactors to generate 9,600 megawatts of power, building just one would be an immense and expensive undertaking. The lumbering progress in completing Kusile and Medupi illustrates South Africa’s dismal record of completing mammoth power plants.

The cost of new nuclear plants also is astronomical. The plants under construction in the United States and China are years behind schedule and cost many times the original estimated price, according to new government and academic studies. A number of recent studies have put the current estimated cost of six new South Africa nuclear plants at more than $US 100 billion.

The Karoo’s seared ground, relentless sun, and temperatures that can change 25 degrees Celsius (77 degrees Fahrenheit) from day to night have driven countless settlers to despair. The ageless desert has been called the ruinous landscape between heaven and hell. Here, the Valley of Desolation in Eastern Cape province. Photo © Keith Schneider / Circle of Blue

South Africa’s capacity to guarantee financing of that magnitude is virtually non-existent. The country’s credit rating is near-junk status. President Zuma acknowledged as much in February during the annual State of the Nation Address.

“We will test the market to ascertain the true cost of building a modern nuclear power plant,” he said. “Let me emphasize, we will only procure nuclear on a scale and pace that our country can afford.”

Scientists have raised alarm about blasting to develop the mines that could affect the seismic stability region where the Square Kilometer Array is planned.

“This billion dollar investment in the Karoo is a direct result of its quiet isolation and seismic stability,” said Christine Colvin, senior manager of Freshwater Programs for WWF South Africa, based in Cape Town. “Fracking and mining throw those essential pre-conditions into question and threaten to literally undermine a global investment in our future.”

A last issue, whether nuclear energy is needed at all, also is emerging in South Africa as renewable energy gains traction. A 2013 study by the South African Department of Energy that projected future electricity demand found no urgency in building a new nuclear plant.

“The revised demand projections suggest that no new nuclear base-load capacity is required until after 2025, and for lower demand not until at earliest 2035,” said the authors of the study. “And there are alternative options.”

Read more of Circle of Blue’s Choke Point: South Africa reporting.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!