‘Mass Aging’ of Dams a Global Safety and Financial Risk, UN Report Says

Countries ought to plan for end-of-life care, report argues.

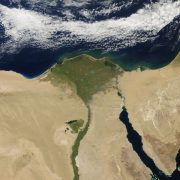

In June 2013, a flood in Uttarakhand, an Indian Himalayan state, killed thousands of people, swept villages away, and seriously damaged the state’s hydroelectric dams and powerhouses. The dam at Vishnuprayag, on the Alaknanda River, was buried in mud and boulders. Photo © Dhruv Malhotra/Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

A global dam-building binge that spanned the early- to mid-20th century is now reaching a turning point, according to a report published by the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment, and Health.

These dams are nearing middle and old age, when their operation and maintenance poses growing financial, environmental, and safety challenges. Though each dam is a unique case, an older fleet has common risks: Rising maintenance costs and declining capacity to store water due to sediment buildup. Continued environmental harm from blocking fish migration and stagnant waters in their reservoirs. And designs that may not stand up to an era of more intense rainstorms and severe weather, putting them in danger of collapse.

The authors write that their purpose is to draw government attention to the problem of aging dams and initiate discussions about end-of-life care so that proper procedures are in place for decommissioning and removing structures whose costs now outweigh their benefits.

“With the mass ageing of dams well underway, it is important to develop a framework of protocols that will guide and accelerate the process of dam removal,” they write.

Several notable dam failures have occurred in the United States in the last five years, from Edenville Dam in Michigan to Spencer Dam in Nebraska to dozens of dams in the Carolinas that crumbled during tropical storms. In 2017, nearly 190,000 people were evacuated downstream of Oroville Dam, in California, after the spillway cracked amid surging outflows during a wet winter.

In 2015, California tore down the 106-foot-high San Clemente Dam on the Carmel River because the dam was at risk of collapsing in an earthquake. Photo via Kelly Grow / California Department of Water Resources

There are more than 58,700 large dams worldwide — a category largely defined by structures taller than 15 meters, or 49 feet. These dams are designed for a range of purposes: to supply water for irrigation and cities, generate electricity, hold mining waste, protect against flooding, and provide playgrounds for boaters.

The United States, one of the first countries to embrace widespread damming of rivers, is now the leader in tearing them down. The conservation group American Rivers has tracked 1,722 dam removals there since 1912. The pace of removals has accelerated. Eighty-five percent have been torn down in the last three decades, including two dams on the Elwha River, in Washington state, which is the world’s largest dam removal project to date.

Most of the removals in the United States, however, have been smaller dams, due to the expense and complexity of taking down larger structures. The Elwha project took more than two decades from planning to completion and cost nearly $325 million.

Just as human health varies among individuals, age alone is an inadequate indicator of a dam’s condition, the report says. Even young dams are risky if they were poorly constructed — Sardoba Dam, which collapsed in Uzbekistan last year, was only three years old. But a rule of thumb is that after 50 years maintenance problems become more problematic.

Many large dams are already in that age range. In North America and Asia, more than 16,000 such structures are between 50 and 100 years old, according to the International Commission on Large Dams. More than 2,300 dams have passed their centennial year. Some countries are dominated by geriatric structures. In Japan and the United Kingdom, the average age of large dams is above 100 years.

Globally, dam building peaked in the 1970s, meaning that the U.S. experience is a precursor. The world is at the cusp of the era of dam retirement, especially in Asia, where China, India, Japan, and South Korea are among the leaders in the number of large dams.

Upmanu Lall, the director of the Columbia Water Center who has studied the risks of aging water infrastructure, said that the report has an understandably clear bias in favor of dam removal. Still, he said that dealing with older dams is a matter of tradeoffs. Though some reservoirs are a significant source of methane, which is a greenhouse gas, hydropower is part of the energy mix to address climate change. The right actions to take will be a matter of weighing risks and securing a financing source.

“At the same time, the risk associated with old, poorly maintained dams is real, and they are not cheap to remove,” Lall wrote in an email to Circle of Blue. “So, this is a conundrum that will take a while to play out.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!