EPA and State Department Square Off On Tar Sands Pipeline

Water use and greenhouse gas emissions are major concerns with developing “unconventional” hydrocarbon reserves.

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

Before July 16, when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued its 18-page letter directing the State Department to more carefully assess the considerable risks of the $7 billion Keystone XL oil pipeline from Alberta, Canada to the Gulf Coast, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was expected to issue a presidential permit approving construction in the fall.

The EPA’s penetrating critique of the State Department’s permit review of the 1,702-mile pipeline, which the environmental agency called “inadequate,” puts that fall schedule on indefinite hold. The question for the oil industry, the governments of Canada and the activists in both countries desperate to tame oil sands development, is what other effects the EPA’s action could have.

The federal environmental agency has good reason to be vigilant. It has been busy since July 26 cleaning up a million gallon tar sands oil spill from a ruptured pipeline in southern Michigan’s Kalamazoo River.

The proposed Keystone XL pipeline, to be built by TransCanada Corp., is the latest of three big oil pipeline construction projects that are at the vanguard of a new era in hydrocarbon development. Instead of drilling deep underground for pools of oil that are getting harder to find and more dangerous to punch open, energy developers are becoming miners, tapping what the energy industry calls “unconventional” reserves contained in oil-saturated sands and oil shales.

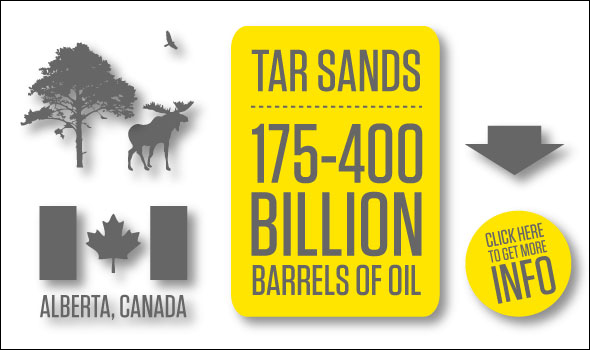

Near the northern end of the Keystone XL pipeline lies Alberta’s bitumen-saturated tar sands, a forested region as large as North Carolina that conservatively contains 175 billion barrels of recoverable oil: enough to satisfy U.S. demand at current rates of consumption until 2035. American, Canadian, Chinese, Korean and European oil companies are spending $15 billion a year to manage and expand immense open pit mines, processing plants, as well as toxic tailing ponds in order to boost production from 1.3 million barrels a day to more than 3 million barrels per day by 2025.

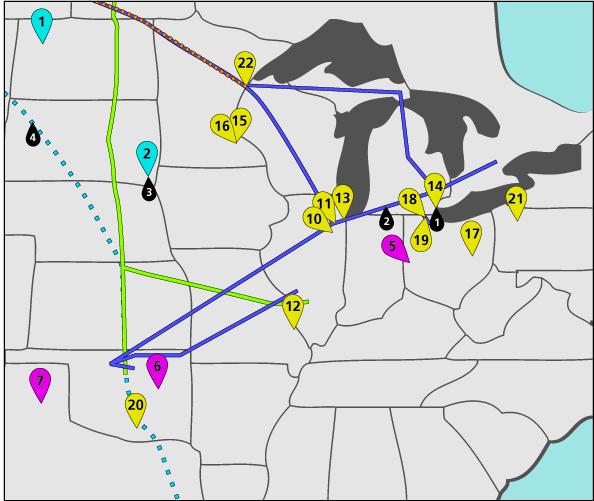

The investment in Alberta is the sharp tip of a long spear of unconventional oil development that reaches into the United States, the primary market. Energy and pipeline companies are spending $31 billion to ship oil in new pipelines from Alberta to U.S. refiners in the heartland, the Great Lakes and the Gulf coast. Refiners are spending more than $20 billion to expand refineries to produce fuels from tar sands oil. In all, the energy industry has said it wants to invest nearly $400 billion on tar sands oil production over the next 15 years.

Contrast that with annual investment in wind and solar energy, which reached $30 billion last year, according to the Department of Energy. Exxon Mobil Corp. paid more than that earlier this year—$41 billion—to purchase XTO Energy, which has big reserves in unconventional tar sands, oil shales, and deep shale natural gas reserves in the United States.

The bottom line is that the race between clean energy alternatives and much dirtier unconventional reserves is an economic mismatch. Last year total investment globally in clean energy was $140 billion, according to solar and wind producers. The fossil fuel industry is spending an estimated three times that amount on developing unconventional oil reserves, according to the International Energy Agency.

Number One Importer

The United States appears completely ready to buy every drop. According to Cambridge Energy Research Associates, the country imports 1.1 million barrels of tar sands oil a day. Alberta’s tar sands have quietly become the largest source of American oil imports and one of the largest new sources of greenhouse gas emissions contributing to climate change.

Oil companies investing in tar sands production and distribution have been very confident that their steady expansion plan will prevail. The U.S. State Department had already approved two other presidential permits to allow big new tar sands oil pipelines to cross from Canada into the country. In April, Enbridge Inc. completed the $3 billion, 992-mile Alberta Clipper from Hardisty, Alberta to Superior, Wisconsin, which will eventually be capable of transporting 800,000 barrels of tar sands oil a day to refineries in the Great Lakes region. TransCanada’s has partially completed the $5 billion, 2,151-mile Keystone pipeline from Hardisty to Illinois and Oklahoma, which will transport nearly 600,000 barrels of tar sands oil to the Midwest. The first oil shipments began on June 30.

But with its letter to the State Department, the EPA became the first U.S. government agency to formally intervene in the rapidly developing and ecologically risky unconventional oil play. The environmental agency’s challenge requires the State Department to rework its first environmental review and develop new data on the pipeline’s effects on greenhouse gas emissions, safety, air quality, water resources, wetlands, wildlife and communities.

Division in the Obama Administration

The letter also revealed a significant schism in the Obama administration that pits energy security against climate action.

On the one hand, the president pledged last year at the Copenhagen Climate summit to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 17 percent below 2005 levels by 2020, and 80 percent by 2050. The White House and the EPA are putting the federal Clean Air Act to work to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles and heavy industry. In April, the EPA issued new vehicle emissions standards for cars and light trucks that the agency said would save 1.8 billion barrels of oil from 2012 to 2016, and reduce emissions by 900 million metric tons.

Both are significant. The annual fuel savings, nearly 400 million barrels, represent roughly 6 percent of all the oil used in America last year, according to the Energy Information Administration. The emissions reductions, roughly 180 million tons annually, represent 3 percent of all carbon emissions the United States produced in 2008, according to the EPA.

Producing and using tar sands oil, though, is blunting those reductions. The 1.3 million barrels of oil currently produced in Canada also produces 40 million metric tons of greenhouse gases annually, or 5 percent of all Canadian carbon emissions, according to the Pembina Institute, a respected environmental research center. According to various estimates by government agencies, non-profit environmental organizations and think tanks, every one million barrels of tar sands oil refined and consumed in the United States produces another 30 million to 40 million metric tons of greenhouse gases.

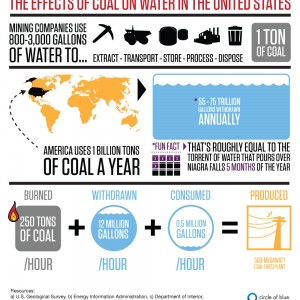

Energy companies are licensed by Energy Alberta, the provincial oversight agency, to withdraw up to the Alberta provincial government granted tar sands oil producers the license to withdraw 652 million cubic meters of water annually—equal to 172 billion gallons—from the Athabasca River, which runs through the mining district. That’s as much water as the entire American oil industry uses in five months.

Big Climate Emitter

The EPA says that greenhouse gas emissions from tars sands mining to finished gasoline and diesel are 82 percent higher than from conventional sources of oil. Every 900,000 barrels of oil carried by the Keystone XL pipeline would produce an extra 27 million metric tons annually of carbon emissions, said the agency.

“To provide some perspective on the potential scale of emissions,” said the authors of the EPA letter, “27 million metric tons is roughly equivalent to annual carbon dioxide emission of seven coal-fired power plants.”

But on the other hand, leaders in the Obama administration are equally concerned about the diplomatic and economic consequences of limiting tar sands development. Clinton and her aides are mindful of the close diplomatic relationship with Canada. The administration’s economic and commerce leaders are interested in securing America’s fuel supply and protecting the $600 billion annual trade between the two nations.

“We’re not going to solve these problems overnight,” said President Obama, who is well aware that the so-called carbon capture and sequestration technology is unproven and only now being sporadically tested by several American utilities.

Obama’s Middle Ground

In February 2009, during his first meeting in Ottawa with Prime Minister Stephen Harper, President Barack Obama discussed the tightening tar sands, climate and energy security knot. He suggested that the solution is to capture carbon during the mining and early processing of tar sands oil and inject the emissions deep underground.

“We’re not going to solve these problems overnight,” said President Obama, who is well aware that the carbon capture and storage technology is unproven and only now undergoing a handful of tests in the U.S. and in other nations.

The pragmatism expressed by the president is supported by a number of energy and climate authorities in Washington, among them Michael A. Levi, director of the Program on Energy Security and Climate Change at the Council on Foreign Relations. In a study last year that weighed tar sands development and climate emissions, Levi wrote that “oil sands production delivers both energy security benefits and climate change damages,” though he also argued both effects were overstated. “For the near future, the economic and security value of oil sands expansion will likely outweigh the climate damages that the oil sands create. But climate concerns cannot and must not be ignored, and will become more important over time.”

But a number of prominent environmental advocates are more adamant. “The main set of concerns around this tar sands pipeline are not around how it is constructed, but about the type of oil it will transport. Bitumen or raw tar sands oil is the dirtiest oil on Earth,” said Susan Casey-Lefkowitz, a tar sands specialist with the Natural Resources Defense Council, in an August 5 blog post. “The United States does not need the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline.

The administration’s decision on the Keystone XL pipeline also is stirring concern among Democrats on Capitol. On June 23, 50 House Democrats signed a letter urging Secretary Clinton to not approve the Keystone XL pipeline.

On July 2, three days after the State Department held a public hearing in Washington on the pipeline, Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.), Chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, sent a letter to Secretary Clinton that raised serious concerns about the effect the pipeline would have on climate change and asking whether the project was “in the national interest.”

“The State Department’s decision on whether to permit this pipeline represents a critical choice about America’s energy future,” said Waxman. “This pipeline is a multi-billion dollar investment to expand our reliance on the dirtiest source of transportation fuel currently available. While I strongly support the president’s efforts to move America to a clean energy economy, I am concerned that the Keystone XL pipeline would be a step in the wrong direction.”

Keith Schneider is a senior editor for Circle of Blue. Contact Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!