Q&A: ‘Crude’ Director Joe Berlinger on Chevron Oil in the Ecuadorian Amazon

Joe Berlinger discusses the three years he spent documenting the international legal battle and the human faces that have emerged from a major environmental disaster of oil contamination in the rainforest.

Welcome to Circle of Blue Radio’s Series 5 in 15, where we’re asking global thought leaders five questions in 15 minutes, more or less. These are experts working in journalism, science, communication design, and water. I’m J. Carl Ganter. Today’s program is underwritten by Traverse Internet Law, tech savvy lawyers, representing internet and technology companies.

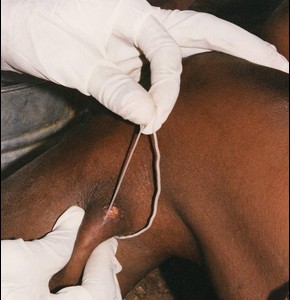

Thirty-thousand rainforest dwellers have taken on one of the largest companies in the world, Chevron, for allegedly having polluted nearly 2000 square miles of the Ecuadorian Amazon. The locals say 50 years of drilling have caused high rates of cancer in their communities; Chevron insists that the inflated illness rates are due to poor sanitation. Chevron inherited the David and Goliath lawsuit–it’s worth $27 billion–when it bought Texaco in 2001. Circle of Blue reporter, Aubrey Parker, spoke with Joe Berlinger about his latest film, Crude. Three years in the making, Crude documents the rising international support for this environmental issue as the lead attorney, a man from the affected area in the Amazon, speaks at Live Earth, graces the cover of Vanity Fair and wins a Hero Award from CNN.

Really, it’s for the viewer to judge as to who’s right, but people have been systematically poisoned. The larger issue of the film is not who should win the lawsuit, but the larger issue that industrialization and oil production, whether it’s legal or illegal, has had a tremendous impact on these people. Basically they have been poisoned, and the area needs to be cleaned up.

Thank you, Aubrey. Circle of Blue’s Aubrey Parker has been speaking with Joe Berlinger, director of the movie, Crude. It’s a film about oil, conflict and water in the Amazon. To learn more about the challenges in the Amazon and to find more articles and broadcasts on water, design, policy and related issues, be sure to tune in to Circle of Blue online at 99.198.125.162/~circl731.

Our theme is composed by Nedev Kahn. Circle of Blue Radio is underwritten by Traverse Legal, PLC. Internet attorneys specializing in trademark infringement litigation, copyright infringement litigation, patent litigation and patent prosecution. Join us again for Circle of Blue Radio’s 5 in 15. I’m J. Carl Ganter.

Aubrey Ann Parker is a reporter for Circle of Blue where she specializes in data visualization. Reach her at circleofblue.org/contact.

___________________________________________________________________________

UPDATE: On May 24, 2010, according to Reuters, Chevron filed to dismiss environmental expert Ryan Cabrera from the case because the geologist violated his legal duties by having ongoing contact with plaintiffs’ representatives. Meanwhile officials from the Amazon Defense Coalition have said Chevron’s claims against Cabrera are another attempt for the leading energy company to evade liability.

is a Traverse City-based assistant editor for Circle of Blue. She specializes in data visualization.

Interests: Latin America, Social Media, Science, Health, Indigenous Peoples

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!