U.S. Urban Residents Cut Water Usage; Utilities are Forced to Raise Prices

As municipal water consumption declines, cities raise rates and civic ire.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Last week the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, one of the nation’s largest municipal water suppliers, announced that along with requiring its customers to use less water under mandatory conservation measures it also would hike up the price for water by 15 percent over the next two years.

The board of the Los Angeles-based water district, which supplies drinking water to nearly 19 million people in parts of Ventura, Los Angeles, Orange, San Diego, Riverside and San Bernardino counties, anticipates a public push back.

Indeed as water sales have declined because of the recession and conservation, water utility boards all across the country have raised rates, prompting civic dismay. A growing number of raucous council meetings, street protests and petition drives in opposition to higher water prices have occurred in cities large and small–Detroit; San Diego; Joplin, Mo.; Prairie Township, Ohio.

In effect, in too many American cities to count, water consumers are dramatically reducing the amount they use only to be hit with higher water rates. Existing designs for deciding water rates are the culprits. A handful of cities are restructuring their billing systems to benefit conservation-minded consumers who deserve to be rewarded rather than penalized.

–Kevin Bakley

The trend favors even more water conservation. A recent report from the Denver-based Water Research Foundation found that the recession has bottled up water demand in many areas of the country-–particularly in regions hard hit by unemployment and foreclosures. And since the mid-1990s, federal law has required new fixtures to be low-flow, meaning they use less water. Showerheads, for instance, are limited to a flow of 2.5 gallons per minute. And toilets can only use 1.6 gallons per flush, down from the 3.5 gallons that were standard in the 1980s.

The unintended consequence of using less in most cities is that ratepayers pay more. The Cleveland region has increased water rates 45 percent to 80 percent since 2007. Cleveland Water Commissioner Chris Nielson explained to the The Plain Dealer last week that “revenue was $25 million below projections last year because of a decrease in consumption.”

“With a deductive reasoning applicable only to a public service monopoly, the answer is to punish the consumers’ conservation efforts with a rate increase,” said Kevin Bakley, a resident and water customer from Strongsville, in a letter to the editor. “At least the return of spring will allow completion of road repairs for the continual, unimpeded egress of corporations and citizens leaving Northeast Ohio.”

Water consumption in St. Charles, Illinois dropped to 1.5 billion gallons last year from 1.68 billion gallons in 2008. John Lamb, the director of the city water department, is preparing a recommendation to the St. Charles City Council to raise rates 4 percent. It would be the third increase in as many years.

“It’s funny, in the sense that it’s a double-edged sword,” Lamb told the Kane County Chronicle. “We tell people all the time to conserve water, conserve water. But then we, as the municipality providing the water, suffer because there’s less money coming in to maintain that system.”

Well, it’s not so funny to thousands of water customers. Ratepayer protests are erupting, many of them in California, a state entering the fourth year of drought. Residents of San Diego submitted 14,000 written protests to the city clerk’s office in November 2009 opposing a new rate–the sixth since 2007–that would have increased the average monthly bill by $4.73.

To a large extent, say some authorities, water conservation should not necessarily translate into higher prices. Rather the system for deciding water rates needs to be redesigned to reward customers who conserve, not lash them.

“There’s no reason why municipalities who implement conservation programs should have to raise their rates,” said Peter Gleick, president of the Pacific Institute. “If that happens it’s a failure of rate design.”

Conservative Conservation and the Death Spiral

Las Vegas water officials call the tradeoff between saving water and raising rates the conservation death spiral. Water utilities are natural monopolies–the cost of delivering water is lowest when there is just one supplier. In the U.S. water utilities are generally publicly–owned and the rules governing each utility differ by city, with most not allowed to make a profit. Any rate increase, even for investor-owned water companies, usually has to be approved by a public service commission. The interjection of public policy and politics is ostensibly to keep the water supplier from gouging the customer, but it has the consequence of affecting a utility’s business incentives.

“Water agencies in the past have tried to keep rates low, in part because of political pressure,” said Heather Cooley, a researcher at the Pacific Institute’s water program. “Members of the board are often elected. It does create problems in the long term, namely failure to adequately invest in infrastructure. Part of the reason utilities are not making those investments is the pressure to keep rates low.”

As a result, cities are often playing catch-up with rates, burning through cash reserves and ignoring system improvements until a rate increase becomes absolutely necessary. Historically, to keep revenue stable, public utilities charged a flat fee for water regardless of how much was used. With the introduction of water meters in the early 20th century, some cities began charging based on the volume of water used, sometimes $2.00 per 1,000 gallons.

The use of meters, however, varied widely around the country. By 1927, 100 percent of the water connections in Portland, Ore. were metered, but this isn’t the case for all cities. To date, Sacramento still has meters in only 25 percent of its houses.

A big shift in pricing occurred in the arid Southwest in the late 1970s. Because of rising use and declining water supply, Tucson, Ariz. instituted an increasing block tariff to encourage conservation. Under an increasing block tariff the cost for a unit of water gets more expensive the more a customer uses. For example, the first eight 1,000 gallon-units might cost $2.00 each, but every 1,000 gallons over that limit would cost $5.00 each, with potentially more tiers added to the rate, depending on the price agenda of the utility.

Fernando Molina, conservation manager at Tucson Water, the city’s utility, explained the circumstances prompting the rate changes in Tucson.

“The 1970s is when the strong conservation movement emerged,” Molina told Circle of Blue. “Back then infrastructure had not kept up with growth. During peak times in summer the utility had trouble meeting demand, especially in the higher elevations in the city. There was a lack of distribution lines and reservoir capacity. When the block rate was introduced it caused a lot of controversy.”

Businesses accused the council of being anti-growth while residents gathered signatures to recall the council. At a special election that fall, every council member who voted for the price increase was voted out of office.

The political fallout in Tucson did not stop the inevitable spread of block tariffs. Cities in which water was scarce had kept the price of water too low and needed to cut rampant use. In areas with limited water supply, block tariffs encouraged conservation by raising the price of consumption for high-volume users. Certain municipalities dealt with the peak demand problems by ordering seasonal rates, which are higher in dry seasons. Though tiered pricing was slow to take hold and poorly implemented where it did, the shift in rates was clear–prices were now a tool to steer conservation.

This is often when death spirals, which are products of utilities allocating costs, occur. Mention conservation and water rates to water managers using a block tariff and they will give you a similar version of the story told by Doug Bennett, conservation manager for the Southern Nevada Water Authority:

“You say [to the customer] we want you to conserve. No rate changes, just a call for conservation. If people react more strongly than you thought they would, then suddenly there’s a revenue shortfall. Now we have to increase rates to recover that. Sometimes we raise rates in upper tiers, but that just increases conservation. The wise thing to do is put it in a service charge or lower tiers, but that sours the relationship with the public.”

Utilities face two major categories of cost: fixed and variable. Fixed costs do not change regardless of whether the utility sells any water or not, such as system maintenance and staff salaries. Variable costs–energy, purchased water, chemicals for treatment–change depending on demand.

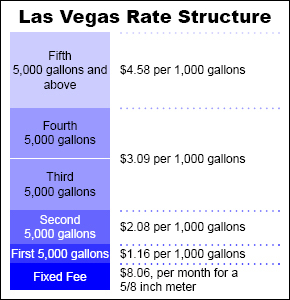

Most utilities charge all customers a fixed monthly service fee in order to pay for fixed costs, but most utilities have a serious imbalance in assigning revenues to costs. While 72 percent of the Las Vegas Valley Water District’s costs are fixed, the utility’s fixed fee covers only 18 percent of its fixed costs. The balance is covered by charges on consumption, so if water use goes down too rapidly the utility gets into financial trouble.

“Water agencies have a disincentive to conservation because if customers cut use, it cuts sales,” Cooley told Circle of Blue.

In essence, water utilities make money selling water. And since selling less water decreases revenue, utilities develop a perverse incentive that welcomes dry periods because people will use more water on their lawns and generate more income for the utility.

Interactive Graphic: Water Data by Selected Cities

“Rising conservation has contributed to revenue volatility,” said Rusty Cobern, budget and finance manager for the Austin Water Utility. “We would have expected a revenue windfall during the [recent] drought. Aggressive conservation pricing model can eliminate windfall opportunities.”

Phoenix is contemplating the same problem. Price increases and education programs have kept water usage stable for the past decade despite a 28 percent increase in population. But now the utility wonders how much conservation is too much.

“How low can we go?” asks Steve Rossi, the principal water resources planner for Phoenix. “From a revenue standpoint, our capital obligations are pretty substantial. Assumptions were made in the past made about revenue flows. We are looking at how things balance down the road if you reduce demand.”

Because publicly-owned utilities are often barred from making a profit, they go through detailed budgeting when setting rates so that they can cover their costs while keeping rates low. Included in these budgets are estimates for how much the customers will conserve. The Marin Municipal Water District in California based its 2009 budget on a projected three-percent decline in sales due to conservation, said Libby Pischel, the district’s public information officer.

As it turned out, customers responded too well to conservation requests, cutting back water use by eight percent, leaving the utility short of cash and forcing an unwelcomed rate increase.

Utilities could avoid the problem by shifting some of their revenue from consumption to fixed charges, but that increases the cost for low-volume customers.

Conservation Instinct Still Strong

Despite the perils of the death spiral, the argument for conservation is strong. Developing new sources of water is expensive, especially as the distance to untapped rivers and reservoirs increases. In Seattle conservation measures have led water managers to predict that the two water supply reservoirs the utility operates will meet the city’s demands until well after 2060.

Conservation can also prevent supply problems during dry periods.

“Long-term conservation improves the supply reliability of system,” said Drew Beckwith, a water specialist with Western Resources Advocates. “If you conserve now, when there’s a drought there will be water in the reservoirs.”

“When I was young I always wanted a rate increase, an aggressive rate structure,” added Bennett in an interview with Circle of Blue. “I wasn’t aware of what the finance people do. It’s really a fine art. What is terrifying to finance people is to throw out rate structure completely and try something new. It’s like cooking — you turn up or turn down the burner. If you throw something big in there it can turn ugly fast.”

“There’s not a lot of benefit to achieving conservation goals ahead of schedule,” he said.

The Irvine Model

Several water utilities have figured out how to resolve the conflict between conservation and revenue.

Irvine Ranch Water District in Orange County, Calif. pioneered a new model when it instituted an allocation-based rate structure in 1991.

Every household is given an allocation based on personal use needs of 55 gallons per person per day and lawn needs based on efficient watering. Customers can apply for an adjustment if there are more people in the house than the utility assumes. A base price is set for the allocation. If a household exceeds its allocated use, it is penalized with rates up to eight times higher than the base rate. On the other hand, if a household is water-frugal it receives a discounted rate.

“Our water rates are the second lowest in our county,” said Fiona Sanchez, IRWD’s conservation manager. “Customers who use water efficiently are rewarded with low rates.”

Not only are rates low, but use is low too. The average customer served by Irvine Ranch uses 52 percent less water per day than the average person served by other Orange County utilities. Efficient use helps to keep prices low by reducing the need to buy water imported from the Colorado River.

IRWD’s success stems from a prudent division of costs and allocation of revenues.

“The key to revenue stability is that we separated fixed and volumetric charges,” Sanchez told Circle of Blue. “We know what our operating costs are and that’s distributed across all customers. If our volumetric sales go down, we’ve got our fixed costs covered.”

IRWD also separated its capital costs from its operations costs. Capital projects to build or maintain water infrastructure are paid for by property taxes and one-time connection fees charged to new users in the system. This keeps water bills in check, but transfers the costs of expansion and repair to a resident’s tax bill.

IRWD customers seemed to be pleased with the system. The utility earns extremely high customer satisfaction scores, and its board members get re-elected, Sanchez said.

Irvine Ranch has conservation, lower prices and customer satisfaction. A handful of utilities in California, because of drought and pumping restrictions, have shifted to allocation-based pricing in the last year and a few others are considering it, Sanchez said.

So why aren’t more following this model?

Data needs are one problem, Sanchez said. The utility needs information about each household’s irrigated acreage. Allocations for lawns are based on micro-climates within the service area and the water requirements from plant use and evaporation.

Another problem is antiquated billing systems, which are often expensive to upgrade.

While there are certainly technical issues to be sorted out, utilities can avoid the backlash from rate increases by improving communication with their customers, the Pacific Institute’s Cooley said.

“Water agencies should be communicating to customers that yes, rates went up in the short term, but it is far less than if we had to build new facilities for a new water source. I don’t think agencies have been good in communicating.”

“I think it’s a failure across the board to engage people,” she added. “It’s a missed opportunity. Most people don’t understand what it takes to provide a clean water supply. When you explain it to them, the utility is able to better maintain a functioning system.”

Residents are looking for leadership from their utilities. At the water rate hearing in Marin County, Calif., board members were urged to make the case for why rate increases were necessary.

“Stop penalizing homeowners who conserve and start rewarding them,” said one resident, the Marin Independent Journal reported.

Brett Walton is a reporter for Circle of Blue. This is part one of his investigation on U.S. urban water rates. He also takes a look higher water prices in Detroit and their effect on the poor. Reach Walton at Brett@circleofblue.org. All graphics were created by Trevor Seela. Reach Seela at trevor@circleofblue.org.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Good post. IRWD is indeed too complicated to implement. Here’s how to do it: http://aguanomics.com/2009/05/fixed-and-variable-costs-redux.html

Where can I find the data on the price per 1,000 gallons for all of these cities?

Governments should not be in the profit making business with public utilities. Therefore, consuming less should cost the same since it means that hte government is consuming less…spending less to give you the same amount.