American Arsenic: After a Decade, Small Communities Still Struggle to Meet Federal Drinking Water Standards

When the EPA lowered the arsenic standard for drinking water from 50 parts per billion to 10 in 2001, there were 3,000 water systems in violation. Today, nearly a thousand still are.

By Brett Walton

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

A decade after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency took aggressive action to limit arsenic in American drinking water, the agency, in its latest assessment published in January, reports that nearly 1,000 water systems serving 1.1 million people are still not in compliance. Worst affected are the 914 small systems that can not find the funds to meet the arsenic standard. But there are a handful of lobby groups, along with legislation proposed in the Senate, seeking to expand federal funding and low-income assistance programs to insulate America’s poorest residents from the rate shocks that would ensue if small utilities had to fully finance their own upgrades.

The inability of a third of the water systems identified a decade ago as a public health concern to come into compliance illustrates the competition between 21st century science, U.S. environmental regulation, and the nation’s economic outlook. Monitoring equipment can identify a problem, and the government can set a standard, but the nation lacks the foresight and funding to solve the problem so that those who have the most need do not carry the heaviest burden.

Federal money for improvements to drinking water treatment wasn’t available until 1997, with the establishment of the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund. Federal funding has typically been directed at sewage treatment. The Water Pollution Control Act of 1956 set federal cost share at 55 percent, providing $US 50 million a year in construction grants for wastewater treatment. In 1972, the Clean Water Act bumped the cost share up to 75 percent, providing $US 18 billion in grants for states to build wastewater facilities.

The cost share, however, fell to 55 percent again in 1981. Then, starting in 1987, grants began to be phased out in favor of state-administered, federally-financed subsidized loans—which, unlike the grants, had to be repaid.

Emblematic of the small system struggle is Andrews, an oil town in West Texas. If residents of Andrews want drinking water that meets the federal standard for arsenic, they cannot get it at home from the public utility. Like much of the Texas Panhandle, the city of 11,000 pumps from wells in the tainted Ogallala Aquifer, where groundwater is laced with naturally occurring arsenic, a known carcinogen, at a concentration of 30 parts per billion, or three times the national legal limit.

To comply with regulations in a way that does not triple or quadruple residential water bills, Andrews officials are beginning a pilot project to install purification devices under the sink in every city home. Forty units are currently being tested in the trial, which runs through April 2012. If it proves successful, the state drinking water regulator will consider authorizing a full deployment. It would be one of the first “point-of-use” technologies approved in Texas as a means for complying with federal drinking water standards.

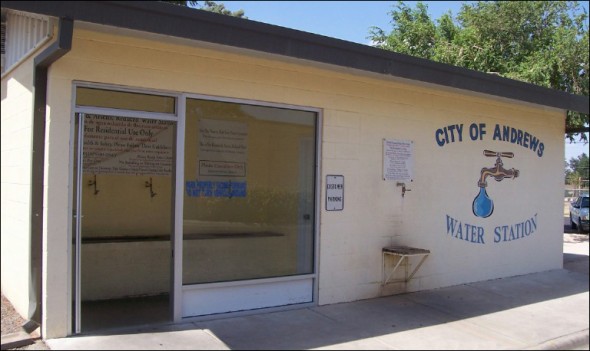

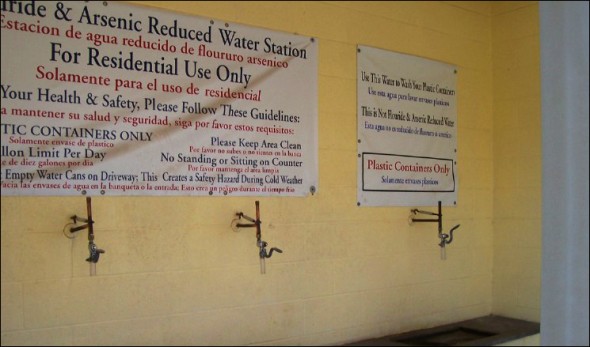

Until then, however, City Hall is the only place in the city to get water that meets arsenic standards set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Three taps jut from the north side of the building, where they can be monitored by the water department offices. One tap is for cleaning containers; the other two are fitted with the purification devices that remove arsenic and fluoride, another contaminant in the Ogallala water source that exceeds federal limits.

Bert Lopez, assistant director of water and wastewater in Andrews, told Circle of Blue that the city supplies 4,500 to 5,500 liters (1,200 to 1,500 gallons) of water per day from these taps to residents who arrive with their own containers. Some come with water bottles, others with 19-liter (five-gallon) jugs. The city, Lopez said, does not track how many people use the arsenic-free source. But, assuming the average person drinks about two liters (half a gallon) or less per day, it is possible that a third to a half of the city’s residents are opting for the public tap, instead of sipping the piped water the city has always used.

“We can go back to well measurements from the 1980s,” said Lopez, who has worked for the city for more than 20 years, “and the arsenic levels have been the same. The standard just got lower. Arsenic has been in the water forever.”

The arsenic ruling, says Ben Grumbles, has raised philosophical questions about regulating drinking water that have yet to be satisfactorily answered. Grumbles, an EPA assistant administrator for water from 2003 to 2008, told Circle of Blue that the ideological battlefield is bounded by two concerns: How clean is clean? And how costly is costly?

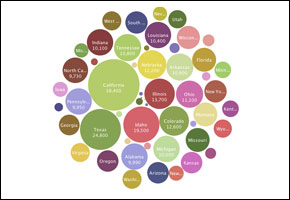

A Decade Later: Systems Not In Compliance

When the EPA issued its arsenic rule in 2001 at the midnight hour of the Clinton Administration, it forced thousands of public water systems to change how they supplied water. The EPA estimated that 3,000 systems serving 11 million people would be out of compliance. In addition, the rule affected 1,100 non-community water systems—places like churches, nursing homes, and factories.

Christie Todd Whitman, the head of the EPA at the beginning of the Bush Administration, said she would review the new arsenic standard, which was being lowered from 50 parts per billion (ppb) to 10. Following a September 2001 report from the National Research Council which concluded that the EPA had underestimated the health risk at 10 ppb, Whitman upheld the previous administration’s decision in October 2001, and the rule went into effect the next year.

Public water systems were given until 2006 to meet the new limit, but they could apply for nine years worth of “compliance extensions” that would give them until 2015 to incorporate new technology into their treatment programs.

The ruling had the greatest effect in the upper Midwest, Southwest, and Northeast, regions where naturally contaminated groundwater is a main supply source. For large systems, this meant installing filtration technology in their treatment plants. Many opted for a process called ion exchange, which swaps benign molecules for arsenic ions as they pass through resin-coated filters. For some small systems, though, that solution would be like adding an airbag to a car without a chassis or wheels—they didn’t have the basic treatment plant to begin with.

Our country does not want a two-tier system, where the water standards are different for those who have money and can pay and for those who don’t.” — Ben Grumbles, EPA Assistant Administrator for Water 2003-2008

“This was perhaps the first time many of these systems had to build infrastructure to come into compliance with federal regulations,” said Jim Taft, executive director of the Association of State Drinking Water Administrators, a professional group for water bureaucrats. “Many are groundwater systems, which typically don’t need as much treatment.”

In 2010, there were 934 documented violators, most of which were small, rural systems serving fewer than 10,000 people—many serving only a couple hundred. Thus, lacking a large customer base, the smaller systems have found it financially difficult to meet standards while keeping water affordable.

The city of Andrews, Texas, is one of those systems.

In Andrews, the water department adds chlorine as a disinfectant, but otherwise the water is distributed straight from the well field. Because of the high cost of a treatment plant—$US11 million to build and up to $US 5 million per year to operate and maintain, according to city water official Lopez—it has been ruled out as a compliance option.

The city is now operating under something called a bilateral compliance agreement, a deal negotiated with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), the state drinking water regulator. For the Safe Drinking Water Act, all U.S. states except for Wyoming have ‘primacy,’ which means they are in charge of monitoring and enforcement. These results are then reported to the EPA, which is the overseeing body. TCEQ appealed to the EPA for less stringent enforcement standards, and the EPA approved the approach in 2006.

Texas is one of the few states to relax its enforcement of the arsenic rule in order to give small communities more leeway until cheaper treatment options are available. The TCEQ has signed compliance agreements for arsenic with 114 public water systems in the state. These agreements allow towns to use bottled water or community taps—like the ones at City Hall in Andrews—to provide arsenic-free water.

But these solutions are not meant to be permanent. Pending the results of its pilot project, Andrews officials have decided in favor of in-home treatment, a program that will cost $US 3 million in capital expenditures and $US 500,000 per year for operations, said Lopez.

Defining ‘Affordable’

The financial burdens of the arsenic rule have been controversial from the beginning. Under the 1996 amendments to the Safe Drinking Water Act, the EPA has the authority to grant affordability variances to small systems. Variances allow a utility to use cheaper treatment technology that improves water quality, but not to the point where it meets the federal standard. This determination comes with a caveat: a variance can be granted only if it does not pose an “unreasonable risk to health.”

This was perhaps the first time many of these systems had to build infrastructure to come into compliance with federal regulations.”– Jim Taft, Executive Director

Association of State Drinking Water Administrators

The criteria for affordability are the national median household income (MHI) and the national median cost of an annual water bill. The EPA has set a theoretical maximum based on the assumption that 2.5 percent of the MHI can go to paying the water bill. In other words, according to the EPA, the average American household can afford to pay about $US 1,200 per year for water, or $US 100 per month.

The difference between this maximum affordable water bill and the current national median cost is known as the “expenditure margin.” If a technological fix, which has been approved by the EPA for health concerns, is expected to cost less than the difference, it is deemed “affordable,” and the utility is expected to make the fix, inevitably by charging the consumer more.

But here’s where the affordability rule rubs many the wrong way: “affordable” does not mean “affordable for every system.”

This is because the designation is a national claim based on estimated costs when the ruling was made—in 1996. Individual systems may find that compliance costs in 2011 go well beyond what their customers are willing, or able, to pay. But, as far as Jim Taft of the Association of State Drinking Water Administrators is aware, the EPA has not reexamined the actual costs associated with compliance actions that have occurred over the last decade.

As it happened for the arsenic rule, the EPA determined that all technologies were affordable and issued no variances. In effect, every public water system, regardless of size, would have to meet the 10 ppb standard by 2015, at the latest.

Avoiding ‘Two Americas’ for Water Quality

The EPA’s decision was criticized on several fronts. The National Rural Water Association (NWRA), a lobby for small water systems, argued that the ruling was unfair to its constituents.

“At the community level, they do not see the need to utilize scarce [financial] resources for arsenic,” Mike Keegan, a NRWA policy analyst, told Circle of Blue in an interview last month. “It requires expensive treatment that is taking away funds from something that would bring a more tangible benefit.” Because the EPA has not yet determined what level of arsenic is an unreasonable health risk, Keegan said communities should have more flexibility in their financial decisions, or they should have more federal support.

“It’s the money for small communities,” said Lopez, the Andrews water official. “The federal government doesn’t offer any compensation. It’s not cheap.”

A bill sponsored in the Senate by James Inhofe, an Oklahoma Republican, would do just that. Inhofe’s bill—which he has introduced every session since 2003 and which has the backing of the NRWA—would:

- Require more federal financial assistance to small communities

- Guarantee that the per-capita cost of compliance would be equal for both small systems and large systems

- Delay enforcement if sufficient funds have not been allocated

A difference regulatory approach was also recommended by the National Drinking Water Advisory Council (NDWAC), a body of water professionals that reviews drinking water regulations for the EPA. In a 2003 evaluation of the arsenic rule, the NDWAC suggested that the EPA revise its affordability criteria to consider incremental costs, which would take into account the cumulative financial effects of multiple regulatory decisions; for instance, the regulation of other pollutants.

Other recommendations from NDWAC included expanded federal funding for upgrades to small systems and a low-income assistance program, established by Congress, to insulate the poorest residents from rate shocks, while still protecting public health. The council cautioned against using variances, saying they should be a last resort because of “pragmatic and ethical concerns” and “the associated connotation of a two-tier approach to protecting public health.”

The EPA briefly considered creating dual regulations, but an agency proposal in 2006 to raise the arsenic standard for small systems to 30 ppb was never enacted. Also never enacted were any of the affordability revisions that had been suggested by the NDWAC, a topic that Grumbles, the former EPA assistant administrator, called “controversial.”

During the interview with Circle of Blue, Grumbles echoed the NDWAC’s concerns that finances should not guide regulations. “Our country does not want a two-tier system, where the water standards are different for those who have money and can pay and for those who don’t. There is a need for innovative procedures to make it cost effective for communities to get into compliance.”

The EPA does have a research program that field tests arsenic-removal technology, and some money is available from the Department of Agriculture’s rural grant program and the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund, a federal loan program for drinking water infrastructure improvements—though that fund can lend only a billion or so dollars annually, and it targets all sorts of capital investments, not just arsenic removal.

What is clear is that the demand for water investment is significantly larger than the federal pot of grants and subsidized loans. The EPA’s latest assessment in 2007 pegged national capital needs for water at $US 334 billion over 20 years, or $US 17 billion annually. Most of that will have to come from revenue and bonds, the biggest sources of utility funds.

Grumbles, now the president of the non-profit Clean Water America Alliance, is spreading the message through his organization that the public needs to reconsider the value of water. Through its outreach programs, the alliance is trying to educate people about their water supplies and the long-term costs of cheap water.

For communities struggling with the arsenic standard, though, the benefits of stewardship are cold comfort in the face of a water bill that has tripled.

And yet, arsenic, the most expensive regulated drinking water contaminant to date, may be just an opening salvo: traces of pharmaceuticals and personal care products have been detected in water supplies and are a growing concern, surely to become candidates for future regulation. Removing these, it is widely suspected, will could be even more costly than arsenic.

Brett Walton is a Seattle-based reporter for Circle of Blue. Infographic by Kelly Shea, a recent graduate of Ball State University’s journalism graphics program and a Traverse City-based designer for Circle of Blue. They can be reached at href=”mailto:circleofblue.org/contact”>circleofblue.org/contact or contact Brett Walton directly.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

I live in Colorado where according to the graphic above Arsenic is not a big concern. However, due to the surronding farms there are many contaminants that threaten our water supply. Instead of buying bottled water which up to 40% of it is just tap water anyway and has an untold effect on the environment. For example Americans drink and discard a half a billion water bottles each week, enough to circle the Earth 5 times!! I decided that the best way to protect me and my family would be to use a water filter. After trying several different brands I finally landed on New Wave Enviro’s Premium 10 Stage Drinking Water Filter. The two stages of Carbon will take out the Arsenic, herbicides, pesticides, chlorine, Voc’s, trihalomethanes etc. It is bacteriostat, has a cation exchange layer, and also calcite which controls the pH of the water. I like it because it is the most complete filter with out going with an RO which strips everything out of the water including the good minerals.

While any filter is better than no filter and definitely better than bottled water. I encourage everyone to check this one out: http://www.newwaveenviro.com/premium-10-stage-water-filter-p-86.html

Great article! FYI it’s not that difficult to remove arsenic form drinking water, we’ve done it for companies, cities and a school, using media, membranes and filtration technologies.

You can view a presentation, and links to a few of our case studies on this page

http://www.water.siemens.com/en/applications/drinking_water_treatment/arsenic-removal/Pages/default.aspx

Communities should not still be fighting to have clean drinking water. Each citizen should familiarize themselves with water regulations to make sure their are safe.

I believe the 2.5% MHI number is for water AND wastewater bills.