Energy Economy Brings Change to Shepherd Life: Modernization Comes to the Dry Grasslands of Inner Mongolia

Along the vast frozen grasslands, 23-year-old Wu Yun and her father, Bao Zhu, tend their herd of sheep and cattle. Just over the ridge, the northern city of Xilinhot is booming as the coal industry expands. But it will take a lot of water to feed both the city and the mining.

By J. Carl Ganter

Circle of Blue

XILINHOT, INNER MONGOLIA — It was here, the vast grasslands of Inner Mongolia, where Ghengis Khan brought his armies to recover, swim in the Nine Bendings River, fatten livestock, and forge swords. In winter, felted yurts protected the Mongols who created the nomadic communities that, for dynasties, have raised sheep on these highlands.

The December day I visit, a frigid blast of razor-sharp ice crystals—some of them blackened from the dust of nearby open-pit coal mines—rolls across the horizon, stopping only to swirl and tear at exposed flesh. Wu Yun, 23, tucks in her mittens and pulls on furry boots to help her father feed the livestock. She hunkers down, unlatches the gate, and lets the sheep out to graze on the fragile, brown stubble. Like minnows, they dart and weave for the open field, protesting the harsh wind with loud baas. An old ram coughs against the cold, stopping for a scratch on the chin.

Wu Yun looks out over the plains, where in summertime she rides her stout horse above the rolling dust. Today the acerbic rasp of smoke from nearby coal-fired power plants winds through the air. On one side, yurts and lambs. On the other, 300-meter-high (1,000-foot-high) buttes made of tailings from Datan International Shengli Mine, China’s largest brown coal mine, which officials say could become China’s largest open-pit mine in a few years.

Brown coal, which has lower energy content than black coal, is the fuel of choice in this part of Inner Mongolia. It is the power source for big electrical generating plants, but it is also piled outside homes, including Wu Yun’s, where it is used for cooking and heating.

Her father, Bao Zhu, breaks loose a few pieces of frozen coal from the pile at the front of their gate. They carry it in together and feed it to the stove in the kitchen. A pot of milk tea boils on the stove, and the heat begins to melt the frost on the windows. In the valley below, they can see the future for Inner Mongolia.

The pile of coal that heats their home in winter is an unmistakable sign of what’s to come.

The shepherd’s life remains simple and raw, guided by the rhythms of the seasons and of the hardy sheep, shaggy cows, and swift horses, able to withstand the -30C (-20F) temperatures and fiercely biting wind. But Xilinhot—an outpost of 177,000 residents that is 600 kilometers (373 miles) and a 12-hour train ride north of Beijing—is at the forefront of China’s energy economy. Just 30 meters (100 feet) below the family farm are the rich veins of the coal that fuel a nation.

Within the next three years, says Wu Yun’s family, the mining company will come to develop the seam. There will be a fair offer they can’t refuse, and they will accept it willingly. They will pack their giant pot of milk tea, sell their horses, cows, and lambs, and move to the city, to an apartment near relatives that have already made the migration.

“When family comes here to visit, they catch cold,” says Bao Zhu. “When we go to the city, we are too warm.”

Modernization in an Energy Economy

Wu Yun puts down her cup of milk tea and prepares for the day. Her generation is part of the urban movement, and she’s already made plans. Wu Yun is studying accounting and wants to open an upscale clothing store to serve Xilinhot’s newest residents, the families of the well-paid miners and workers who come to mine the brown gold. But the city will also need water, to hydrate its growing population, as well as the thirsty mines.

Xilinhot is at the center of the Xilin Gol Grassland, one of China’s largest prairies and livestock production regions. As Circle of Blue first reported in 2006 and again in 2010, the Xilin Gol Grassland has suffered severe sand encroachment and desertification. But now the deliberate and unhurried lifestyle of pastoral farmers faces yet another hurdle.

Coal from Xilinhot—where proven reserves number around 30 billion metric tons (33 billion short tons), while provincial and academic authorities say unproven reserves total to hundreds of billions of metric—travels to power plants as far away as the Yangtze River Delta region. Large wind farms are also located near Xilinhot, with 200 turbines currently operated by seven different energy companies and another 200 turbines are expected to be built in 2011.

Additionally, more than 30 kinds of minerals have been found in the area, one of which is germanium.

The rare-earth mineral, a semi-conductor metalloid, is a byproduct of the pulverizing process of Xilinhot’s brown coal. The crushed coal rumbles along kilometers of conveyor belts in the local mill. The factory hisses and moans, churning out the white powder, which, ironically, is a key ingredient in the production of solar cells and the circuitry that controls the high-tech and cleaner energy alternatives like wind farms and smart grids.

In 2006, the worldwide production of germanium was roughly 100 metric tons (110 short tons), and, in 2007, recycled germanium met 35 percent of global demand, according to High Beam. Worldwide reserve figures are not currently available, though the China Daily reports that Xilin Gol may have China’s largest deposit of germanium. In contrast, the U.S. is estimated to have 500 metric tons (550 short tons) of germanium reserves.

While the Shengli Mine could soon become China’s largest open-pit mine, plant managers at the Shangdu Power Plant in Zhenglan, only 20 kilometers (12 miles) away, hope to expand the facility to be the largest power plant in all of Asia, according to the China Daily.

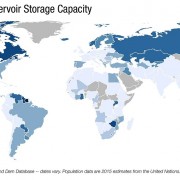

Standing in their way, though, is the region’s limited supply of fresh water, which is needed to mine and wash the coal, as well as to cool coal-fired power plants. There are nine rivers and 28 lakes in Xilinhot, and the total annual water resources tally to 260 million cubic meters (68.7 billion gallons), with 160 million cubic meters (42.3 billion gallons) available for use. More than 90 percent of this is groundwater, with only 11.3 million cubic meters (3 billion gallons) available to use as surface water.

So, while Bao Zhou has to drive 15 kilometers (9 miles) every few days to fetch water for his herd—groundwater on the plains has dropped precipitously and much of it is contaminated by heavy metals, chemicals, and the city’s sewage—energy companies will, nevertheless, secure what they need. There are plans to bring water to the dry northlands to feed the thirsty mines:

- A 600-kilometer (400-mile) pipeline from eastern China’s Bohai Sea, where 340,000 cubic meters (90 million gallons) of seawater would be desalinated daily for the mines and processing plants.

- The western line of the North-South Water Transfer Project, currently in the planning stages, which, when finished in 2050, would transfer 22 million cubic meters (5.8 billion gallons) per day to Qinghai, Gansu, Shaanxi, and Shanxi Provinces, along with the Ningxia Hui and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Regions.

It is this scale of design and thinking—highly controversial, too—that underscores China’s water-energy challenge and the huge infrastructure that the nation is looking to put into place, starting in the cold and snow-blown fields of Xilin Gol Grassland.

J. Carl Ganter is director and co-founder of Circle of Blue. Reach him at carl.ganter@circleofblue.org.

Contributions by Aubrey Ann Parker a Traverse City-based editor, and by Jennifer Turner, Washington, D.C.-based director of the China Environment Forum at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

J. Carl Ganter is co-founder and managing director of Circle of Blue. He is a journalist and photojournalist, recipient of the Rockefeller Foundation Centennial Innovation Award, and an Explorers Club Fellow.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!