Building China’s 21st-century Megacity: Shanghai’s Experiment with Water and Nature

A new community on the Yangtze River has, so far, been more successful at attracting ducks than people. But city officials have their sights set high for Lingang Port City, which they say could be home to nearly a million people by 2050. Cleaner water will be a big help.

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

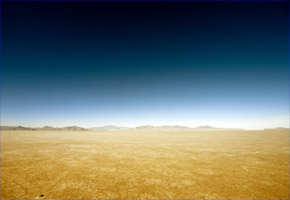

LINGANG PORT CITY: Shanghai, China — Dishui Lake, constructed where the Yangtze River meets the East China Sea, is a perfectly circular manmade lake that was meant to put people in close proximity to fresh water.

The Nanhui Dongtan Wildlife Sanctuary, which lies on Dishui Lake’s eastern bank, is a 122.5-square-kilometer (47-square-mile) expanse of tall grasses and shallow, rain-fed ponds that also tests the lure of fresh water; in this case, to recruit great flocks of migratory birds.

From 2003 to 2005, both the lake and the sanctuary were constructed from silt and mud, carried downstream by the Yangtze and captured with long rock and concrete groins that engineers extended into the river’s mouth. Shanghai’s planning officials envisioned using the new ground to build a seaside district — Lingang Port City — that was intended to attract thousands of businesses and 400,000 residents by 2020; 800,000 residents by 2050.

The idea for this new borough was to reduce crowding, build contemporary commerce centers, and encourage lower population densities in Shanghai, a city of 23 million that is tallying 1 million additional residents every two years. If Shanghai were an American state, only California and Texas have more people.

— World Expo 2010 Theme

Shanghai

The enterprise hasn’t quite worked out the way planners in Shanghai’s city government envisioned, however. For the time being, the wildlife sanctuary has been much more successful in attracting winged residents than neighboring Lingang Port City and its lake has been in recruiting businesses and human residents — yet.

Shanghai city managers know how to build a 21st-century city, and they are doing so with a clear focus on environmental values and energy efficiency, in addition to improving the quality of the water supply and expanding the size and number of parks and open spaces.

Better City, Better Life

Last year, Shanghai hosted a World Expo with the green-oriented theme: “Better city, better life.” Among the innovations promoted was Shanghai’s ongoing program to establish new and planned residential and business districts outside the core central city.

Lingang Port City was one such example, featuring big runs of green space, lots of clean water on display in canals and ponds, and countless new energy-efficient homes and offices. All of these new districts will be tied to the central city and to each other via Shanghai’s clean, fast, and steadily expanding subway system, which now consists of 11 lines, 267 stations, and 410 kilometers (255 miles) of track.

In 2002, Shanghai opened a Maglev train line from the downtown area to Pudong Airport. The train, which operates on powerful magnets that lift the cars onto a thin cushion of air, travels 431 kilometers an hour (267 miles per hour) and makes the trip in less than 7 minutes — 40 minutes less than in a taxi.

The Urban Land Institute, based in Washington, D.C. and one of the premier U.S. urban planning and development research organizations, reviewed Shanghai’s master plan in 2006 and declared: “No other city in history has attempted to tackle its urban issues with such a comprehensive program of public improvements and new-town development at its periphery.”

Dishui Lake, the centerpiece of the Lingang Port City district, was intended as a showcase of the city’s master plan. With a diameter spanning 2.5 kilometers (1.5 miles) and a surface area of 5 square kilometers (2 square miles), Dishui has three sizable, grass-covered peninsulas that serve as green open space. From a birds-eye view, the peninsulas resemble continents and the lake — round as a dime and about 60 kilometers (37 miles) to the south of Shanghai’s high-rise central core — looks very much like a replica of Planet Earth. On its northern and western banks, the lake is surrounded by a constellation of new residential and office towers, the mostly uninhabited dark stars of Lingang Port City.

On the lake’s southern and eastern flank, though, lies the great expanse of freshwater ponds and grass reclaimed from the Yangtze estuary that is, for the time being, much more successful in attracting wild residents.

Big Water Cleanup

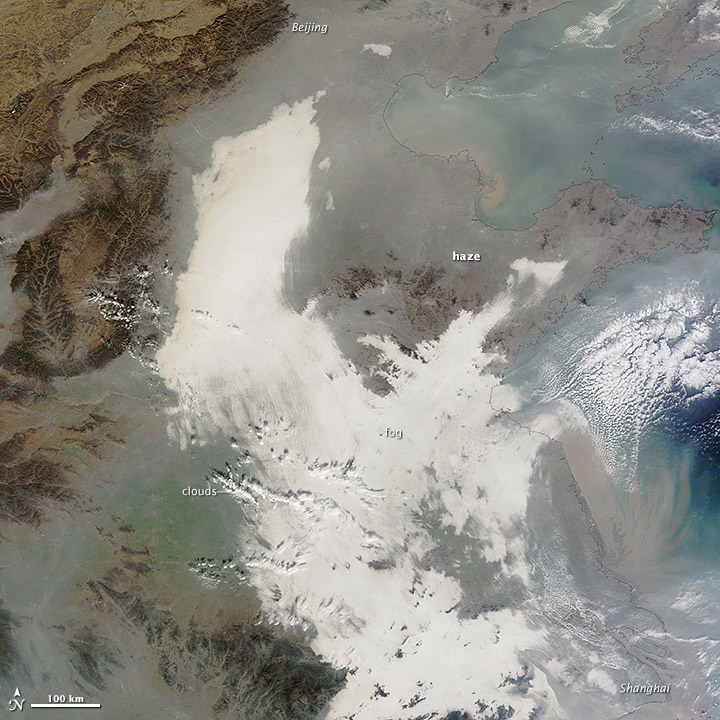

Though people have yet to show up in droves, filthy water is not one of the district’s impediments. Since 1995, Shanghai has spent $US 8.1 billion (RMB 50.3 billion) to construct a network of 52 sewage plants that now treat nearly 80 percent of the city’s wastewater, according to the Shanghai Municipal Oceanic Bureau, a city agency. In contrast, Shanghai had only five treatment plants during the late 1980s — one of which was constructed in 1921 — and 80 percent of the city’s sewage poured, untreated, into rivers and lakes.

The source of Dishui Lake’s water is the Huangpu River, a tributary of the Yangtze River, that runs through the center of Shanghai. While still unfit for swimming and difficult to treat for drinking, the Huangpu is nevertheless much cleaner than it was 20 years ago, meaning that fish can survive and it no longer has an overpowering odor.

One advantage is that Dishui Lake’s walkways and grassy shoreline parks are busy on weekends with families and couples who drive down for the day from Shanghai to enjoy such large expanses of uncrowded ground.

Upstream, meanwhile, the Huangpu serves as the watery ribbon decorating the soaring office towers — outlined at night by laser-edge red, blue, and yellow LED lights — of Shanghai’s spectacular Pudong New Area. Only 20 years ago a geography of farms and marginal lands, Pudong now accounts for more than $US 63 billion (RMB 400 billion) in annual gross economic activity in this city, or 26.9 percent of the Shanghai’s annual GDP, according to the Shanghai Bureau of Statistics. Had the river been as fetid as it once was, the foreign investors that helped build one of the world’s most impressive skylines along the Huangpu’s southern bank might not have been nearly as interested.

Growth and Development = More Energy, More Water

That kind of economic growth, though, also is unnerving Shanghai residents and pressuring the region’s resource base, especially for energy. The city’s energy consumption has increased by 250 percent from 1995 to 2010, in part because Shanghai is pumping and processing 12.52 billion cubic meters (3.31 trillion gallons) of water annually for its growing array of industries and residential developments, according to the Shanghai Water Authority. This is about twice as much water as was pumped and processed during the late 1990s.

Almost 60 percent, or 7.33 billion cubic meters (1.94 trillion gallons) annually, is used by the city’s power producers, including the 2,000-megawatt Waigaoqia plant, an ulta-super-critical coal-fired generating station — the world’s most efficient, according to Siemens, which helped build it.

Additionally, Shanghai treats 2.3 billion cubic meters (608 billion cubic meters) of wastewater annually, or seven times as much as it treated in 1988, when the city began its big push to clean up polluted waterways.

As Lingang Port City and Dishui Lake await what city officials are convinced will be a wave of new residents, they are promoting the area as a “green city, wisdom city, and healthy city.” Perhaps the most significant lesson that a Westerner could draw from such a message is the capacity of a wealthy government to make decisions that so readily illustrate the limits of centralized decisions, as well as their optimism and promise.

— Yong Yi,

Environmental Scientist

In 2009, for instance, as new residents and businesses failed to appear around the four-year-old Dishui Lake, a decision was made to merge the Lingang government district with the Pudong New Area government. The big merger, which was completed last year, emptied the government campus buildings on the northern shore of Dishui Lake. Hundreds of city jobs moved out of the district.

But a big transportation infrastructure project — the expansion of Line 11 of Shanghai’s subway system — is expected to produce a new station stop near Dishui Lake, perhaps as early as next year, that should help to link the distant new district with the rest of the city, now reachable only on Shanghai’s busy highways.

People Not There, Wildlife Is

But the empty eight-lane boulevards are deserted, as are the newly constructed business and residential neighborhoods of Lingang Port City. But, in ways big and small, Dishui Lake and its neighboring bird sanctuary also represent the big strides that Shanghai, China’s largest city, has taken to leverage natural landscapes and to clean up its freshwater resources, thereby enhancing the metropolitan region’s impressive prosperity and building a healthier quality of urban life.

This is especially true, explains Yong Yi — a 33-year-old environmental scientist and the senior program officer for the Shanghai office of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF, formerly the World Wildlife Fund) — for a low-lying coastal city in an era of warming temperatures, rising seas, and more violent storms.

Yong was part of a group of environmental leaders and city officials who helped establish the sanctuary in 2007. The area, she says, has a certain magical attraction for people in an urban center, where big natural spaces are scarce.

Very clearly the rain-fed sanctuary is achieving much of what Yong and her colleagues anticipated. It is attracting so many birds that 11 conservation officers are needed — most of whom spend the bulk of their time preventing poaching.

Qing Wang, a conservation officer in the Nanhui Dongtan Wildlife Sanctuary since 2008, tells how he and his colleagues sometimes spend winter nights hiding in the marsh grass to catch poachers. On one particularly grim day in September 2009, conservation officers discovered illegal hunting had netted 3,000 small birds, which were destined to be sold for food. A poster showing those 3,000 birds — lined up in a room, in neat rows — now hangs on the wall of a sanctuary building as a reminder.

Early on this still and overcast September morning, Wang frowns, pointing at the poster on the wall, and makes it clear that the event from two years ago hurt him.

Over his shoulder and through the doorway, the heavy equipment of Shanghai’s emergence as a global capital is readily event. Big jumbo jets coast north on the landing flight path to Pudong Airport, the city’s international gateway. Ocean-going ships make their way upstream to Shanghai’s docks. The tops of Lingang Port City’s tallest buildings, where city officials say they want to install green roofs, are visible.

Yong peers into the dark water of one of the sanctuary’s shallow ponds. In the distance, about two kilometers (one mile) to the west, the tops of the buildings around Dishui Lake are visible. A flock of ducks, the vanguard of the thousands that will begin their winter layover next month, pass by overhead. In front of Yong rest the unrippled, gray-metal waters of the East China Sea, held back by a big concrete and earthen dike.

“You can see the city. You can see the sea,” Yong says. “Here are wetlands, nature, birds, fish — people and nature can live together — that’s what you see when you come here. Shanghai is an estuary city. These are the kinds of places the city must see as valuable to protect itself.”

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!