Map: NASA Shows Big Dip in U.S. Groundwater Regionally, Especially Near Texas Drought

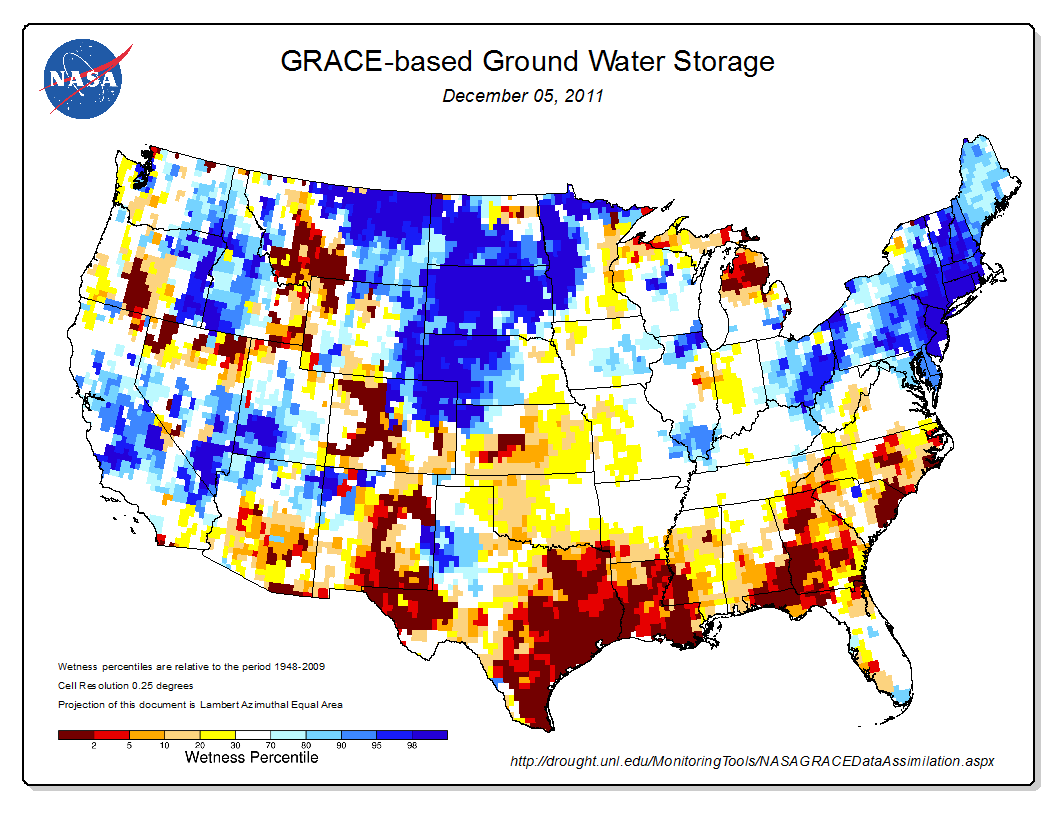

Using calculations based on satellite observations and long-term meteorological data, a new map shows that groundwater is extremely depleted across more than half of Texas, as well as areas of Alabama, the Carolinas, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Michigan, Montana, New Mexico, and Oregon.

The worst Texas drought in more than a century has reduced groundwater throughout most of the state to the lowest levels in more than 60 years, according to a new map by scientists at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. (The December 5 map, shown below, has been updated from the November 28 map, which was used in the NASA press release.)

These maps are generated weekly by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, by entering long-term meteorological data and satellite observations into a sophisticated computer model. The meteorological data includes precipitation, temperature, solar radiation, and other ground- and space-based measurements, while the satellite observations come from NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites, which can detect small changes in the Earth’s gravity field that are caused by the redistribution of water on and beneath the ground’s surface.

The color-coded maps show some regions of the United States where current ground moisture is significantly lower than the long-term average, dating back to 1948, when the levels of groundwater and soil moisture were first recorded. In the map above, the maroon shading over eastern Texas, for example, indicates that the level of dryness over the last week has occurred less than 2 percent of the time during the past 63 years.

“Texas groundwater will take months or longer to recharge,” said Matt Rodell, a hydrologist based at Goddard, according to the NASA press release. This year’s Texas drought pitted farmers, cities, and power plants in a vicious competition for water, and dry conditions are expected to continue into 2012. “Even if we have a major rainfall event, most of the water runs off. It takes a longer period of sustained greater-than-average precipitation to recharge aquifers significantly.”

Scientists have suggested that these maps could prove useful for policy makers, farmers, and water managers as a new tool to monitor the health of critical groundwater resources and to distinguish between short-term and long-term droughts.

“People rely on groundwater for irrigation, for domestic water supply, and for industrial uses, but there’s little information available on regional to national scales on groundwater storage variability and how that has responded to a drought,” Rodell said. “Over a long-term dry period, there will be an effect on groundwater storage and groundwater levels. It’s going to drop quite a bit, people’s wells could dry out, and it takes time to recover.”

The weekly maps are publicly available on the National Drought Mitigation Center’s website.

Source: NASA, National Drought Mitigation Center, Yale Environment 360

, a Bulgaria native, is a Chicago-based reporter for Circle of Blue. She co-writes The Stream, a daily digest of international water news trends.

Interests: Europe, China, Environmental Policy, International Security.

I was surprised to see the state of the ground water in Michigan’s top of the mitt. Is there any evidence that this may be partly, or wholly due to the bottle water industry located in the area?

This is a vital issue that policy-makers, news medias, educators and voters should all keep abreast of. Are these groups currently well represented in your distribution base? If not, we should urge them to keep dip-sticking the water news and supporting the efforts that keep us aware of this life-sustaining resource.

Thanks for your valued and impressive efforts.

Beverly McCann

Beverly,

That surprised us too, since our headquarters is in Traverse City, MI. I asked our contacts at NASA and Drought Monitor, and they didnt have any answers for us because there are only two wells in N. Michigan that are monitored by USGS. One well is down compared to the long-term average, the other is up. He suggested that we speak to additional sources in Michigan that monitor more groundwater wells, which is something that we are pursuing now, trying to get answers.

Do you know anyone we should be speaking to, anyone who monitors groundwater wells?

Thanks for your comment,

Aubrey Ann Parker

Circle of Blue Assistant Editor