New Wind and Solar Sectors Won’t Solve China’s Water Scarcity

Clean alternatives help, but not nearly enough, to loosen energy-water choke point.

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

Photographs by Toby Smith/Reportage by Getty Images for Circle of Blue

Updated

JIUQUAN, China—Business for wind and solar energy components has been so brisk in Gansu Province—a bone-bleaching sweep of gusty desert and sun-washed mountains in China’s northern region—that the New Energy Equipment Manufacturing Industry base, which employs 20,000 people, is a 24/7 operation.

Just two years old, the expansive industrial manufacturing zone—located outside this ancient Silk Road city of 1 million—turns out turbines, blades, towers, controllers, software, and dozens of other components for a provincial wind industry already producing more than 5,000 megawatts per year.

Chen Xiao Yan, a 25-year-old assistant in the New Energy Industry office, said Sinovel, Goldwind, Dongfang, Sinomatech, and 21 other clean energy manufacturers have established plants at the base. Two of those developers also produce equipment for Gansu’s expanding solar photovoltaic industry, which at the end of this year will generate 120 megawatts of electricity.

Within three years, 10 additional manufacturers will build plants in the base, increasing the workforce to 50,000 employees, Chen said in an interview with Circle of Blue.

“It’s what we do here,” she said with a shrug. “We produce energy.”

Northern Gansu is doing that and considerably more. This region of dust and industrial innovation—about as far west from Beijing as Montana is from New York—has very quickly become a booster stage for China’s rocket ride to the top of the global water-sipping clean energy heap. Prompted by a national decision in 2005 to diversify the nation’s energy production portfolio, and to do so with the goal of reducing water consumption and climate-changing carbon emissions, Gansu and its desert neighbors are pursuing clean energy development with a ferocity unrivaled now in the world.

Along with northern Gansu, there are six other wind energy bases and eight other solar power bases being built in China—most of them in the desert regions of northern and western China. China also has a burst of seawater-cooled nuclear power plants under construction along its eastern coast.

China’s National Energy Administration projects that, over the next decade, generating capacity from wind, solar, and nuclear power will more than quadruple, from 53 gigawatts in 2010 to 230 gigawatts in 2020. The other big non-carbon electrical producer is hydropower, which is expected by the government to grow to 400 GW of capacity by 2020, up from 213.4 GW last year. (For reference, one gigawatt, or GW, is equal to 1,000 megawatts, or the generating capacity of a big nuclear- or coal-fired power plant.)

Wind energy now accounts for 42GW, or 16 percent of the nation’s non-carbon electrical generating capacity. China’s energy officials projected last year that wind energy generating capacity will rise to 150 GW by 2020, though many wind industry executives predict the number will reach more than 200 GW.

Solar generating capacity is expected to jump from less than one GW in 2010 to 20 GW by 2020. Nuclear power is projected to increase from 11 GW to 60 GW in the next decade.

Yet China’s demand for electricity is rising so quickly that the massive investment in new generating technologies will not make nearly as large of a dent in production—or in freshwater conservation—as many people might expect. Simply put: wind, solar, and nuclear power will climb to around 13 percent of the 1,900 GW of generating capacity expected by 2020, according to government data. That’s up from the nearly six percent of the 960 GW of generating capacity today.

The new wind, solar, and seawater-cooled nuclear plants will replace roughly 100 big coal-fired generating stations, which equates to a savings of 3.5 billion cubic meters (nearly one trillion gallons) of water annually, according to academic and government estimates. The clean energy stations also will eliminate around 750 million metric tons of climate-changing emissions annually.

But China’s national water use—599 billion cubic meters in 2010—is anticipated to grow by 71 billion cubic meters by the end of the decade. And the increase in water consumption, a good portion of which is spurred by new coal production, is occurring in a nation that is steadily getting drier. (See sidebar)

Put another way, the $US 738 billion that government authorities promised last year to spend on non-fossil fuel power generation over the next decade will jump start China’s clean energy economic transition. The enormous solar and wind-related manufacturing plants across China already employ tens of thousands of people. They are irrefutable evidence of the capacity of clean energy to spur job growth. They also are a signal to the United States and other nations that China is prepared to dominate wind, solar, nuclear, and other cleaner sources of power that global energy economists predict will eventually generate trillions of dollars in revenue each year.

But clean energy development will not solve the commanding threat to China’s modernization – the confrontation between rising energy demand and declining reserves of fresh water. Over the next decade, and likely well beyond that, the water savings from solar, wind, and seawater-cooled nuclear power will not be nearly enough to loosen the noose that water scarcity is steadily tightening around China’s coal production and combustion sector, and its national economy. (See sidebar)

“There may be an ultimate day of reckoning approaching,” said Nicholas Lardy, a senior fellow and China specialist at the Peterson Institute in Washington D.C. “But there are a lot of intermediate steps China is prepared to take and already is taking to hold it off as long as possible.”

No Turning Back

Chinese development officials insist they have no intention of backing away from the country’s rapid modernization or from using every available energy-producing option to fuel that growth. A powerful transition is occurring in China, much of it focused on attracting new pioneers to the dry northern and western provinces. The strategy appears to be working.

The modern cities under construction in Gansu Province, Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Ningxia, and Jilin are supported by new factories turning out steel, aluminum, vehicles, appliances, wind turbines, mining equipment, and hundreds of other products intended to supply China’s rapidly expanding domestic markets. High-rise apartments are under construction in clumps of 30-story concrete towers in every major city. Streets and highways are jammed with late-model and expensive cars. Restaurants are full day and night. Long lines form at checkout counters in Western-style grocery superstores.

The provincial economies of northern and western China are growing at a faster rate than the national gross domestic product, which reached 10.3 percent in 2010, according to the latest government figures. The new regional growth has been spurred, in part, by clean energy production and manufacturing, which China recognized was a good fit for the windy, sunny, and dry geography.

A province with 25 million residents and about the same geographical size as Sweden, Gansu has managed energy production and water scarcity for decades.

Oil was discovered around Yumen in the 1930s, and a sizable production and refining industry thrived for over half a century. One of the historical highlights of Gansu’s energy industry is that Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao, a trained geologist and China’s second most powerful political figure, spent the early part of his technical and government career from 1968 to 1982 managing Gansu’s mineral and water resources.

In 1996, provincial officials began to experiment with replacing northern Gansu’s oil sector with wind. They installed four 300-kilowatt wind turbines at the Yumen Jieyuan Wind Power Plant. Cities in Xinjiang, to the west of Gansu, and the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, east of Gansu, also joined Gansu as the first provinces to experiment with utility-scale clean energy generation.

The sector grew steadily—albeit slowly—for nearly a decade, said executives here in Jiuquan. But, in the earliest years of the new century, wind power began to spin with economic authority.

Prompted by internal concern for the conflict between water scarcity and rising energy demand and the goal of developing new industries that could employ millions, China enacted the world’s most aggressive renewable energy law in 2005. China’s National Development and Reform Commission declared that, by 2020, 15 percent of the country’s energy would be produced by wind, solar, biomass, and hydropower—up from 7 percent at the time.

Since then—and mindful of the external diplomatic pressure surrounding China’s soaring climate-changing emissions—a host of other new policies and publicly financed incentives have been enacted to promote clean power that uses less water.

In 2007, China established a new “water intensity” requirement that calls for industry and agriculture to cut the amount of water they use per unit of gross domestic product by 20 percent. In 2009, that target was increased to 60 percent.

The government also mandated that taxpayers share in the cost of developing renewable power with a small fee on their utility bills. Electric utilities are required to buy power from renewable energy producers, which were provided with low-interest loans from the government. China also protected its manufacturers, requiring that at least 70 percent of all wind turbine components must be manufactured in the country. Five of the 15 largest wind turbine manufacturers in the world, as a result, are now Chinese.

Similar incentives were enacted for the solar industry.

The public incentives, combined with China’s determination to both diversify its power sector and develop new job-producing industries, have pushed the country to the front of the global renewable energy industry.

Energy and Water Vectors Cross in Gansu

One of the places that has served as a testing site for the new era of water-sipping clean-energy production is the northern deserts of Gansu, where evidence of China’s big play in clean energy development is in plain view. The New Energy Equipment Manufacturing Industry base—a collection of state-of-the-art clean-tech manufacturing plants—is the largest noncarbon-energy manufacturing center in the world, said Chinese energy officials in Jiuquan.

The base sits at the southern end of a region of wind farms that stretch for miles and encompass more than 5,000 wind turbines. There are also two solar photovoltaic power plants, which are the first in a 25-square-kilometer sun power zone outside Dunhuang that will have the generating capacity of 12 GW by 2025.

Gansu, in other words, hosts one of the largest clean energy zones on Earth. The investment in wind power alone will soon reach nearly $US 18 billion, according to provincial figures. The goal is to install enough capacity to generate 20 GW of wind-powered electricity by 2020, according to Wu Shengxue, deputy head of the Jiuquan Municipal Development and Reform Commission.

In Dunhuang, an art and tourist center near the border with Xinjiang, Ren Tao—a 42-year-old engineer who’s an expert in water supply and energy production and is the general manager of SDIC’s 10-MW solar photovoltaic demonstration plant—described the new solar installation. The year-old, $US 18 million plant is the first utility-scale solar plant connected to China’s transmission grid. It sits at the center of the sunniest region in China and operates more than 3,000 hours a year.

Across the road, a second 10-MW solar photovoltaic plant—built by CGNPC Solar Energy Development Company—began operations late in 2010.

“My challenge,” said Ren, “is to prove that we can produce a lot of energy from the sun at low cost. Green energy is the only option we have to develop this country in a way that reduces pollution, reduces water use, and develops Chinese society.”

Huang Xiao, another of the young professionals managing Gansu’s clean energy industry, is similarly committed. The 25-year-old woman is the executive of general affairs at Sinomatech Wind Power Blade Company, which operates a 40,000-square-meter (430,000-square-feet) plant, employs 1,000 people in Jiuquan, and last year turned out 2,400 wind blades.

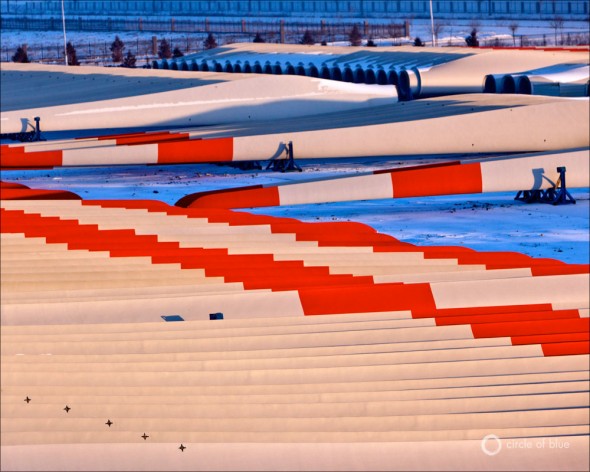

Outside her office window, more than a hundred 40-meter white blades, marked by bright red slashes at the tips, are neatly lined up in a staging area, ready to be shipped. There are two other companies in the New Energy Equipment Manufacturing Industry base that produce comparable numbers of blades for Gansu’s wind sector. With three blades installed for every turbine, Gansu’s three wind blade companies are producing 7,200 blades annually, which are enough to install 2,400 industrial-scale turbines per year.

Even in frosty December, the highway leading from the manufacturing base to some of largest wind farms on the planet is a steady trail of diesel trucks carrying blades, turbines, and white-painted steel towers. The newly constructed four-lane expressway runs right through the wind power zone, where thousands of white, Chinese-made turbines stand in some of the country’s strongest and steadiest mainland winds.

Roughly 5,500 turbines have been installed in Gansu Province and thousands more are planned. Energy developers have built new dormitories in the desert for the 15 to 20 workers required to manage and maintain individual wind farms, which typically have 500 turbines.

By 2015, the miles of turbines and wind farms concentrated around Yumen, a small desert city in northern Gansu, will produce 10 GW to 12 GW of generating capacity, said Shi Pengfei, vice president of the China Wind Energy Association. China’s other big wind regions—Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, Jilin, Hebei, and offshore in Jiangsu—also are developing rapidly.

“This all makes a lot of sense for China,” said Qiao Yu, a 30-year-old senior engineer who oversees the China National Offshore Oil Company’s wind farm near Yemen. “We can not always rely on oil and gas and coal. The climate here is changing and our water supply is going down. Nothing can last forever. We must get involved in new energy. Chinese people and the government realize how important this is.”

This post has been revised to reflect the following updates:

Update: August 15, 2011

This post has been revised to reflect the March update by China’s National Bureau of Statistics, which estimated the 2010 water use at 599 billion cubic meters, instead of 591 billion cubic meters, as was reported by China’s Ministry of Water Resources in December 2010. An earlier version of this article reported that the annual water consumption of China’s coal mining, processing, and electrical generating industries consumed 112 billion cubic meters of water in 2010. A revised estimate by the Chinese government in July reported that those three sectors consumed 120 billion cubic meters of water in 2010.

Keith Schneider, who has reported on energy, water, and climate change from four continents, is senior editor for Circle of Blue. Contact Keith Schneider

Map and graphic by Mark Townsend, Megan Capinegro, Katelin Carter, and Chelsea May, undergraduate students at Ball State University, with contribution by Aubrey Ann Parker, a Traverse City-based data analyst and news desk editor for Circle of Blue. Reach Parker at circleofblue.org/contact.

Toby Smith is a British photojournalist represented by Reportage by Getty Images who specialises in global energy and environment matters. His further work can be viewed on his website and he can be reached at: toby@shootunit.com

The Choke Point: China series is produced in collaboration with the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars China Environment Forum.

Next: A Dry and Anxious North Awaits China’s Giant, Unproven Water Transport Scheme.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Hey, I’m currently in a class on the relationship between water and society at the University of Washington in Seattle. An assignment asked us to take a critical look at some water journalism and provide a critique. I’m posting that below. I’ll cut out all the summary of the article content and get straight to the juicy stuff:

The article, New Wind and Solar Sectors Won’t Solve China’s Water Scarcity, touts China’s renewable energy sector as a major solution to the water demands of China’s enormous energy production industry; however, Mr. Schneider, does little to explain these claims beyond pointing out wind and solar energy’s low water footprint and coal’s high water footprint. In fact, there are more efficient and less efficient methods of water use in coal production. In China’s scramble to fulfill its energy needs, it has implemented mostly pulverized coal power plants. Coal gasification is a far more efficient way to produce power, but requires a greater investment in technology. Other aspects of coal production can have major effects on coal’s water footprint. Slurry pipelines use water to transport coal, but pulverized coal slurry pipelines use far more water than compressed-log pipelines. As previously mentioned, underground mining is far more water costly than open pit mining.

Among renewable energy production, the same sorts of distinctions exist. The disparity can hold true: a large scale photovoltaic power plant produces energy at 1 gallon/MWh, whereas coal requires 538 gallons/MWh (Pasqualetti, 2007). Unfortunately, photovoltaic power plants are not the only form of solar energy production. Solar Thermal power plants do require large quantities of water to be heated for steam to move turbines, creating twice the water impact of coal. Wind is the only renewable form of energy production not associated with any water use (except for in the production of the wind turbine, which is negligible). According to Mr. Schneider, increases in wind and solar power production from 50 to 200 GW will be met with an increase in hydropower from 150 GW to 400 GW a year. Hoekstra et al. (2008) explain how hydropower can have a significant impact on water use: “Dams in rivers create large water reservoirs. The water requirements for hydropower are mainly caused by evaporation and seepage from the reservoirs and are about 5-26 m3 per 103 kWh (electric).” Hydropower’s water footprint dwarfs that of solar thermal and coal. Schneider also mentions increases in nuclear energy production. Not only is the uranium mining water intensive, but power plants must be cooled by water and use water to produce steam to turn turbines as well, which is greater than coal at 785 gallons/MWh (Pasqualetti, 2007). Therefore, of the increase in renewable energy from 7 percent of total energy production to 15 percent in China, the majority of that causes greater water scarcity instead of alleviating it.

The most important distinction the article fails to make is the one that hits closest to home. The article only takes a cursory look at what factors are driving demand for energy and water. There is no recognition of the concept of virtual water, which is defined as the water used in the production of a good. The consumer of the good is the one ultimately responsible for that water use. China exports $US 1.2 trillion worth of goods per year. China has the largest cotton production – incredibly water intensive – of any country on earth and textiles are one of their biggest exports. Much of China’s water use is not local consumption, but global consumption. Circle of Blue, the institution publishing this article, also investigated water use and energy demand in the United States, coming to the conclusion that “A number of environmental, economic, and political impediments lie in the path to large increases in American energy production. None, though, is more significant than the nation’s steadily diminishing reserve of fresh water.” Clearly, the US is circumventing natural limits on fresh water use by importing industrial goods. Therefore, water shortage is not a Chinese problem, but a problem for all developed countries that import goods from China.

Excellent analysis on Wind and Solar in China and water scarcity.The spectacular achievement of China in Wind and Solar is laudable.

Dr.A.Jagadeesh Nellore(AP),India

Wind Energy Expert

E-mail: anumakonda.jagadeesh@gmail.com

There is definately a great deal to learn about this topic.

I like all the points you have made.