Off the Deep End — Beijing’s Water Demand Outpaces Supply Despite Conservation, Recycling, and Imports

How China’s capital got in over its head, and what the city is doing to get its water crisis under control

By Nadya Ivanova

Circle of Blue

BEIJING—The 200-kilometer drive from Beijing to the Guanting Reservoir in Hebei Province takes you from the urban jungle of China’s capital to the dry farm fields and tumble-down villages of one of the country’s major agricultural regions. On this early December morning, the air is breezy and tinged with cold, and the sun gleams on the frozen Guanting water through thin, wispy clouds.

A farmer, hungry and frustrated, sits by an ice-fishing hole in the reservoir and skittishly lifts his gaze from the pit to make sure there is no one else around. He is nervous. The reservoir is exclusively reserved, according to unwritten rules, for the local government officials. He might get fined more than $US 1,200 (RMB 8,000)—four times his annual salary—for fishing for food for himself and his family.

His uneasy look underlines a widespread, but unspoken, tension. Once a magnet for tourism and booming agriculture, this area of eastern Hebei Province can no longer provide enough water for irrigation. To feed the thirsty Chinese capital, Hebei’s Guanting Reservoir has lost more than 90 percent of its water, and the nearby Yongding River, which filled the entire flood plain in the 1980s, is down to a trickle. The Beijing government is now paying the area to cut back on irrigation, yet farmers say that local authorities don’t give them any of the subsidies that compensate for the losses.

“What can we do? If you don’t let us irrigate our crops, we have no other options [but to fish],” the farmer mutters, declining to give his name before he hurries away.

He will soon return, with an empty sack, to his home in an impoverished village not far away, joining hundreds of farmers, dirt-poor and desperate, whose lands and lives are roiled by fierce water shortages, water pollution, and lack of job opportunities. Competition from neighboring Beijing has prompted government water managers to divert much of this area’s water for the residents, industries, and parks of China’s capital.

To a remarkable extent, the story of this Hebei county on the border with Beijing illustrates the desperate measures that the Chinese capital is taking to avert an impending water crisis for its population of more than 19.6 million. Perennial drought, overuse, and pollution have left Beijing struggling to meet the growing water demands of its soaring economy, which is expanding by more than 11 percent a year on average. Its drying rivers and lakes, along with falling water tables, are enduring water deficits that force the city to suck millions of cubic meters (billions of gallons) in emergency transfers from neighboring provinces—which, in turn, depletes their water supplies—thereby draining agricultural and economic opportunities.

In essence, Beijing is at the bull’s-eye of a potentially ruinous collision between accelerating growth and scarce freshwater reserves that is unfolding in China’s dry and resource-rich northern provinces. Beijing’s municipal government, though, is acting with authority and some speed to avoid a water crisis. The city is relocating thirsty industries to the coast, regulating water prices, and cutting back on irrigated farmland. Beijing also is setting nationally significant standards for retrofitting sewage treatment systems to recycle wastewater for use in flushing toilets, washing cars, greening urban parks, cooling thermal power plants, and other gray-water applications.

Water Recycling and Imports

New office and residential buildings in Beijing are required to have separate plumbing systems for fresh water and for grey water, say municipal officials. Central Beijing is rapidly closing in on its goal of recycling close to 100 percent of its wastewater for use as gray water by 2015, Hui Li told Circle of Blue. Hui is the deputy general manager of the Qinghe Regenerated Water Plant in Beijing, one of nine wastewater recycling plants in the city.

“This plant is making a difference in China,” said Hui, who is 31 and serves at the plant, which recycles 80,000 cubic meters (21 million gallons) of wastewater daily. “The plant is helping us become cleaner and greener.”

Along with helping Beijing conserve water, the Qinghe Regenerated Water Plant also is conserving energy. The $US 160 million plant (RMB 1 billion), which employs 22 people, is in the midst of an expansion that will raise recycling capacity to 450,000 cubic meters (119 million gallons) per day by 2013 and cost $US 600 million (RMB 4 billion).

The plant, though, is capable of using just 0.4 kilowatt-hours of electricity to recycle a cubic meter (264 gallons) of water, or a total of 180,000 kilowatt-hours per day when the expansion is completed. That is much less energy than is needed to pump and transport the same amount of water from outside Beijing. For example, it can take about 2 kilowatt-hours to raise a cubic meter of water to a height of one meter.

Though water recycling in Beijing is a big help, it’s not nearly enough. The capital city’s growing population and rocketing economy, as well as climate shifts, are steadily depleting its rivers, lakes, and underground aquifers.

This winter, Beijing endured the 12th straight year of severe drought, and the winter dry spell was the worst in the last 60 years. Two thirds of the city’s water comes from groundwater and one-third from surface water, but average annual precipitation in the Beijing area has dropped 30 percent since the turn of the century.

Beijing’s two main drinking reservoirs, Miyun and Guanting, are 90 percent empty. Four years ago, Guanting, with a designed capacity of 4.16 billion cubic meters (1.1 trillion gallons), shrank to almost a puddle.

Declining surface water supplies, along with the growing population, are also forcing deeper drilling into Beijing’s shallow aquifers, which have already dropped by more than 10 meters (33 feet) since 2000. Some 60 kilometers (37 miles) outside the city, villages have to sink wells more than 1,200 meters (3,900 feet) into the ground to get water.

The city’s water use—currently around 3.6 billion cubic meters (950 billion gallons) a year—now outstrips the available local water resources by more than 1.3 billion cubic meters (340 billion gallons). And this water gap will only grow larger, as the population and economy are set to increase and climate change is disrupting patterns of rain and snowfall.To avert a looming crisis, Beijing is transporting water from outside the city, at the expense of neighboring provinces, particularly Hebei.

Farmers have been forced to switch from rice to corn in order to save water, and farm acreage has been reduced to save water for the thirsty capital city. In a bid to relieve the water shortage, more than 200 million cubic meters (52.8 billion gallons) of water was transferred from three Hebei reservoirs to Beijing during the second half of 2010 alone.

In 2014, Beijing will start receiving as much as 1 billion cubic meters (264 billion gallons) annually from the central line of the South-North Water Transfer, a massive infrastructure project that takes water from the Yangtze River Basin to the thirsty cities in the north. And, in a measure of desperation, the city will begin diverting 300 million cubic meters (97.2 billion gallons) of Yellow River water annually, starting this year. In 2011, the Beijing government will set aside $US 3.5 million (RMB 23 million) to buy water from other provinces.

Quenching The City’s Thirst

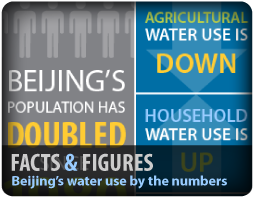

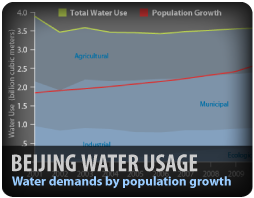

Beijing is acutely aware of its water crisis. In recent years, the city has implemented successful water conservation measures that have scaled down water use from its peak of 4.8 billion cubic meters (1.3 trillion gallons) in 1980 to about 3.6 billion cubic meters (940 billion gallons) in 2010, while its population has more than doubled.

Beijing has also closed a number of paper mills, fertilizer factories, textile plants, and heavy industries to reduce industrial water use by more than 40 percent. In 2009 alone, Beijing shut down 49 industrial facilities. It also moved to the coast the giant Capital Steel factory, which annually used 60 million cubic meters (15.8 billion gallons) of water.

Meanwhile, the city has cut down on irrigated farmland, improved irrigation practices in millions of acres and, in turn, reduced agricultural water use—which accounts for about a third of total use—by more than 30 percent since the turn of the century.

Besides cuts in the industrial and agricultural sectors, Beijing also aims to reduce the municipal water use of its growing population. The city treats more water and wastewater than it recycles, but great strides are being made in both sectors to conserve. Overall, Beijing treats about 80 percent of its wastewater. Sewage treatment in the suburbs is just over 50 percent, but the Beijing government plans to increase this figure to 80 percent by mid-decade.

Likewise, the city’s central area has increased wastewater treatment from about 50 percent in the years leading up to the 2008 Olympic Games, which were held in Beijing, to more than 95 percent in 2010, according to Li Kui Xiao, engineer at the Beijing Water Research Center. By 2015, sewage treatment is expected to reach 98 percent in the city center.

The Gaobeidian Wastewater Treatment Plant, the biggest in Beijing, alone treats 1 million cubic meters of water a day (264 million gallons), which is primarily discharged into the rivers and parks in Beijing’s central area.

Following Beijing’s major overhaul in preparation for the Olympics, the city has been retrofitting its sewage treatment systems to recycle a portion of its wastewater for non-potable uses, such as washing cars, flushing toilets, greening urban parks, and other gray-water applications.

The city’s wastewater recycling rate is expected to increase from the current 60 percent, or 700 million cubic meters a year (184 billion gallons), to about 75 percent, or 1 billion cubic meters (264 billion gallons), by 2015—the highest in China. In comparison, Shanghai does not recycle any of its water.

Beijing is also increasingly building new housing units with gray-water plumbing systems, kept separate from potable tap water supplies. In 2009, there were about 200 Beijing communities receiving gray water.

To meet the 2015 targets in both the wastewater treatment and recycling sectors, the city plans to upgrade and expand several of its nine wastewater treatment plants, along with building three new facilities in the suburbs. By mid-decade, Beijing will invest up to $US 3 billion (RMB 20 billion) to improve its water infrastructure, said Bi Xiaogang, deputy director of the Beijing Water Authority.

Limits of Saving

Just how much momentum Beijing’s conservation practices have built is still unclear. Even with current measures in place, Beijing’s water use will climb to 4.1 billion cubic meters (1.1 trillion gallons) by 2015, according to Bi. The city’s municipal use, which accounts for nearly half of the overall use, has grown 25 percent since the turn of the century, while the overall water supply has decreased by about 8 percent during the same period.

“[Water recycling] can’t solve Beijing’s water problems,” Li, the Beijing Water Research Center engineer, said. And, he added, modernizing the city’s plumbing and recycling system will consume more energy—roughly 0.2 to 0.4 kilowatt-hours to treat a cubic meter of wastewater. This, in turn, will drive up the price of water, which currently is about $US 0.38 (RMB 2) to treat one cubic meter of wastewater.

Many experts predict that the city’s growth will likely outstrip its water saving measures and its planned water transfers.

Indeed, despite importing water from the outside, Beijing is currently 515 million cubic meters (135 billion gallons) short of water demand. Even after the full launch of the South-North Water Transfer Project, which will start supplying water to Beijing in 2014, the city will still have a water deficit of 190 million cubic meters (50 billion gallons) a year, according to People’s Daily, the Chinese government’s mouthpiece.

Looking Ahead: Subsidies and Sea Water

In other attempts to conserve, Beijing has raised water prices for residential use several times, from US$ 0.25 (RMB 1.6) in 2000 to the current $US 0.61 (RMB 4), but the fees are still too low to cover the real costs of water supply. Even though the water tariffs across China have doubled on average in recent years, they are still some of the lowest among the world’s major economies.

Beijing’s policy-to-date of guaranteeing (through subsidies) water supply at little or no charge to consumers has so far done little to increase water savings. Bi was reluctant to give details on the effect of the South-North Water Transfer on water prices, saying that the city government “will consider the marginal profit—if we can afford this economically and socially.”

Because water from the transfer project will likely be very expensive—some 400 wastewater treatment plants and more than 60 pumping stations will be used to treat and transport the water along the eastern line alone—neighboring Tianjin is currently looking into more viable options.

Desalination plants could turn seawater into fresh water at considerably lower cost than what it would take to ship and purify water from the south, said city managers. Tianjin now boasts a $US 1.85 billion (RMB 12 billion) desalination plant that can supply 200,000 cubic metres (53 million gallons) of drinking water annually from the sea at a cost of about $US 1.20 (RMB 7.9) per cubic meter. Unofficial estimates measure the real value of the South-North Diversion water at $US 1.20 to $US 1.50 (RMB 7.9 to RMB 9.7) per cubic meter.

“The unit water cost of desalination is actually cheaper than that of the South-North Water Diversion Project,” Zou Ji, the World Resources Institute’s China country director, said in an interview with research group Asia Water Project earlier this year. “Many coastal cities, including Tianjin, Qingdao, and Dalian, have integrated desalination into their middle-to-long-term blueprints as an alternative water resource.”

But desalination and wastewater treatment require more energy, and energy requires water—all in areas where the water-energy collision is already visible and growing worse—making the large-scale production of desalinated water economically unfeasible. Even with the most advanced technology available, producing a cubic meter of desalinated water uses 1.5 to 3 kilowatt-hours of electricity. Meanwhile, each kilowatt-hour produced from thermal power, on average, requires at least 0.1 cubic meter (25 gallons) of water, not counting the water needed to mine and wash the coal.

“The government does not clearly recognize this problem,” Junfeng said. “They put a lot of hope on South-North Diversion and seawater desalination. One of their main points is that as long as the GDP grows, we can just buy the water.”

Nadya Ivanova—who has reported from China, Europe, and the United States—is a Chicago-based reporter and producer for Circle of Blue. Reach her at circleofblue.org/contact. Aaron Jaffe, a Chicago-based reporter and photographer for Circle of Blue, and Keith Schneider, Circle of Blue’s Traverse City-based senior editor, contributed reporting. Reach Jaffe and Schneider at circleofblue.org/contact or contact Keith Schneider directly.

Contributions by Jennifer Turner, Washington, D.C.-based director of the China Environment Forum at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Research assistance by Zifei Yang, research intern at the China Environment Forum.

Graphic by Justin Manning and Stephanie Meredith, undergraduate students at Ball State University.

, a Bulgaria native, is a Chicago-based reporter for Circle of Blue. She co-writes The Stream, a daily digest of international water news trends.

Interests: Europe, China, Environmental Policy, International Security.

At Karachi Water & Sewerage Board (KW&SB), Karachi, Pakistan, we are facing similar problem that our Water Demand Outpaces Supply.

Hope, we may learn something good from our Chinese brothers.

Overall, this site is quite informative.