Photo Slideshow and Q&A: Om Prakash Singh Documents the Perception and Harsh Realities of Water and Sanitation in Delhi, India

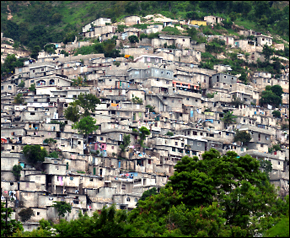

Delhi reportedly has a high percentage of coverage for sanitation and water supply. But one photographer has 74,000 images spanning the last 10 years that challenge the perception of progress.

Om Prakash Singh, a Stockholm-based visual anthropologist and director of WaterZoom, has spent the past decade documenting water and sanitation challenges in India. Through his work, mostly in the poorest areas of Delhi, he has captured more than 74,000 images of private, everyday moments of life with limited water and without a proper toilet to use. His exhibit of photographs, “Urban Right to Water & Sanitation,” was on display at World Water Week 2011 in Stockholm. It was produced with his wife, Nandita Singh.

For example, these pictures come from Delhi. Half of these pictures are only seven days old. But, according to reports and other places, Delhi is 100 percent covered for water supply, as well as for sanitation. This absolutely is not [consistent with] my observation. Through these photographs, I am trying to expose the reality. And, also, through this exhibition, we are sensitizing the different stakeholders, big actors, to get back to the real situation and organize a realistic action plan. And, thirdly, with this exhibition, I am trying to convince and push a lobby for the use of documentary photography as a means of effective communication in water resources management. It’s emotion, and you get involved immediately, and you get sensitized. And you help your own intelligence to understand that and get involved immediately. We have covered 15 states in India – that are huge, it’s like 50 countries – and depicted different issues on water resources management and sanitation.

So in books, in records, Delhi is 100 percent covered, but this is [not the real] situation. You feel very emotional that, “Oh my God, for such a basic need, they have to queue for hours and hours, and they can’t even be sure that [water] will turn up. They have to wait for hours and hours, even just to have it fail.” I’ve waited for hours and hours with the people. Just seven days ago, I was in Delhi, and I was there at 6:00 in the morning. It’s a daily activity, you know – the tanker is supposed to go there to deliver the water supply. But many people have been waiting much before then. I started at 6 o’clock, and I waited until 9:30. The tanker didn’t [come], and people had to return without water, even after waiting so many hours. See, you can now imagine the hardship. The statements of the people are so touching sometimes: “We are here to own a glass of water.” So most of their productive time goes for waiting for water or for procuring the water for their domestic use.

What will happen to these people now? No agencies, no NGOs, nobody will be bothered about them because “that area is covered. So let’s go to a new area!” Because they [the agencies and NGOs] have limited resources and funding, and they want to go to new areas to make things work.

And [it is] such an unhygienic condition – you can’t stand it for even a moment. Yet, they are standing there for hours and hours. And we are talking about hygiene – what is this? So the most private thing has become a public thing.

And that’s such a small child, carrying such a big load of water. That means, at the same time, he doesn’t have time for recreation, which will certainly undermine his whole development. It’s not just a question of rich-poor colonies or slums.

And in this photograph you see [leaking pipes with hoses collecting every drop]. Normally people say that there’s wastage of water to leaks, but, just imagine if this water were not there — there would be no water, in fact. So, the people are basically utilizing the water. Thousands of people are collecting from the leaks of the pipeline. And see the amount of water they are carrying? Because they have to walk on this pipe, with this heavy load of water in their hand, they always get injured.

And about the sanitation, look at this picture along the Yamuna River: is this water – physically or visually – is there anything that tells you that you can use this water for any purpose?

Similarly, in the case of sanitation, this is a mobile van [with bathrooms]. You can practically see that the ladies are asleep. They are completing their sleep here, because they have to come early in the morning to get chances first. If they don’t turn up, they will be far behind in the queue, if the pressure comes. They have to go out; they are forced to go out [early in the morning]. And that is why they are defecating openly — some of them are defecating in storm water drains. And how safe are storm water drains? They are destined to go to fresh water, maybe ponds, lakes.

Circle of Blue provides relevant, reliable, and actionable on-the-ground information about the world’s resource crises.

Situation is not very different from New Delhi, in other parts of the country. Leaking water from pipes is only source of life for some people in many cities of India. Scenario is equqlly worse in rural areas. Villagers dont have drinking water. Half the villages in Maharashtra are facing water scarcity. Manyy villages are tanker-fed, even in monsoon season. I stay at Aurangabad, and I’m an engineer from BITS, Pilani , working in the field of water conservation for the last 17 years. I have invented a low cost method for harvesting 80% pf rainwater, which can solve drinking water problems of villages. Anyone facing water scarcity can contact me on my email for free advice on rainwater harvesting. My email is jalmitra@varshajal.com .

Anyone can join ‘KFP network for water conservation’ on my Facebook page for details about RWH.

Congrats for such a real, thought-provoking, and fascinating presentation.