Rains Bring Relief For Six-Month China Drought, But Chronic Water Problems Loom

Although now satiated, the dry spell is the latest in a growing trend of severe water shortages threatening China’s food production, energy generation, and accelerating modernization.

By Nadya Ivanova

Circle of Blue

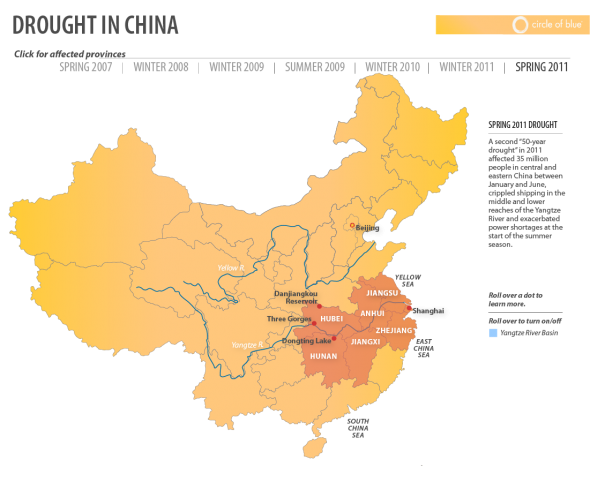

Heavy rainfall began in China last Friday, easing the effects of a prolonged drought that has been ongoing in the nation’s central and eastern regions since January. Though this spring’s dry spell has affected 35 million people across five provinces in the Yangtze River Basin—leaving 3.5 million with limited access to drinking water—analysts predict limited impact on national food production, consumer prices, and power output.

The extreme weather, however, is the latest in a series of water shortages exposing the risks that limited freshwater resources pose for the world’s biggest agricultural producer, top energy consumer, and fastest-growing industrial economy.

This is the second tenacious dry spell in China this year. During the winter, severe water scarcity in the northern wheat-growing regions threatened to cripple harvests and forced farmers to dig deeper into declining underground aquifers. Now, the drought that was gripping the typically lush Yangtze River Basin suspended cargo shipping along a 224-kilometer (140-mile) stretch in the middle and lower reaches of the river and exacerbated power shortages at the beginning of what is typically the peak summer season.

As Circle of Blue and the China Environment Forum have been reporting since February, droughts and water shortages across China are now occurring with such frequency that they are putting the nation’s farm productivity and energy generation at risk, while modernization demands and global commodity prices are steadily increasing.

Economy, Eats, and Energy

This spring, rainfall in Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Jiangsu, and Anhui provinces—the home of China’s “rice and fish”—has been the lowest in half a century, down 40 to 60 percent from normal precipitation levels, according to statistics from the State Flood Control and Drought Relief Headquarters.

— Bryan Lohmar

Bunge China

And while experts are still assessing the overall impact of the drought on China’s economy, the direct economic losses in the affected provinces are nearing $US 2.3 billion (RMB 15 billion), according to China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs.

The dry spell spread across more than 7 million hectares (17.3 million acres) of farmland, or one-eighth of China’s arable land, and affected the early crops of rice and water-intensive vegetables. Moreover, it hit at the heart of the Yangtze River Basin, at the source of the central line of the South-North Water Transfer Project, which is slated to annually supply 13 billion cubic meters (3.4 trillion gallons) of water from southern China to help curb enduring water shortages in more than a dozen northern cities.

In an effort to relieve the effects of the recent dry weather, more than 19 billion cubic meters (5 trillion gallons) of water have been released since January from the Three Gorges Dam, the largest hydroelectric project in the world. At the peak of the drought, the water levels at the reservoir were four meters (13 feet) below the minimum level to run its turbines effectively, Xinhua reported.

The Hydropower-Coal Connection

The drought has crippled hydroelectric power generation down the Yangtze, official reports say, and the timing couldn’t be worse. Hydropower could be a cheap alternative to high-priced coal, as energy producers scramble for ways to offset substantial losses. Though coal prices are soaring, energy producers can’t raise consumer prices because of tight state control over electricity fees, and are instead cutting power output to save money.

In May, China’s top five power utilities—which generate half of the country’s electricity—reported $US 1.62 billion (RMB 10.5 billion) worth of losses in their coal-fired power plants during the first four months of the year, according to the Xinhua News Agency. China’s main electricity distribution company, the State Grid, warned that power shortages this year could reach 30 to 40 gigawatts, even if coal and water supplies are normal for the season.

Yet, some analysts say that the dry spell that has gripped the Yangtze region underlies bigger problems in China’s water and power management.

“I can’t imagine that all the hype is just due to natural drought,” said Bryan Lohmar, the Shanghai-based director for economic research at Bunge China, an agribusiness and food company. “I believe there’s water held up in the Yangtze to generate power [that is] not coming downstream. People are seeing the lower levels of the Yangtze, and they are calling it a drought. And, actually, it’s a common conflict between upstream hydropower users and downstream water users.”

Such scenarios echo the brutally long drought in southern China, which, in early 2010, gripped the flows of the mighty Mekong, Salween, and Yangtze rivers, nearly shutting down the 6.4-gigawatt Longtan Hydropower Station, China’s second largest.

The drought, which directly affected nearly 18 million people, dramatically lowered water levels in rivers that generate much of China’s 213 gigawatts of annual hydropower capacity and are also used to transport coal to power plants.

— Fred Gale

USDA

The irony, say environmental experts, is that the runaway dam-construction that is clogging rivers in the south—a region that, according to government statistics, is at the same time slowly losing moisture, thus reducing water levels and hydropower capacity—has prompted authorities to import more coal in order to maintain electricity output during droughts. It is also choking the water flows downstream.

Economic and Agricultural Impact

Though analysts are just starting to assess the damage to crops in central and eastern China, the early rice crop typically accounts for 15 to 20 percent of China’s yearly output.

“I think it will mainly affect the early rice crop, which is harvested in early summer, but that’s not a really big part of China’s rice crop,” said Fred Gale, a senior economist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service. “Most of the rice is harvested in the fall and hasn’t been planted yet. So it’s not clear whether that’s going to have a real major impact on the grain harvests as a whole.”

Experts say the weather in July and August—the crucial growing period—will be the major factor for the final output.

“China is a huge country,” Nicholas Lardy, a senior researcher at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, told Circle of Blue. “It’s very hard to trace a macroeconomic impact of droughts. While some regions are always doing poorly, others are doing well and are offsetting the overall impact.”

Though China has been experiencing frequent droughts, its annual grain production has increased by nearly 10 percent since 2006. Last year, China produced 546 million metric tons (602 million short tons) of grain, representing an increase of 15.6 million tons (17.2 short tons), or 2.9 percent, from the year before.

“In the broad context, China has been increasing production, and the droughts have had surprisingly little impact on the overall production,” Gale said. “One factor is irrigation—that’s what saved the wheat crop this year.”

Despite the dry spell that affected the winter wheat crops in the northern provinces earlier this year, China is expected to further increase its grain output in 2011. The nation’s 12th Five-Year Plan, the economic blueprint that will guide China through 2015, plans to keep the grain capacity above 540 million metric tons (595 million short tons) a year, and increase the arable land by 2.6 million hectares (6.4 million acres) over the next five years to satisfy growing demand.

The nation also plans to further limit annual water use in the next decade, the state news agency Xinhua reported, and has earmarked $US 608 billion (RMB 4 trillion) over the next 10 years to clean up its rivers and lakes, fix its water supply systems, and boost water conservation and irrigation.

— Nicholas Lardy

Peterson Institute

But even these measures are likely to leave northern China with more than 20 billion cubic meters (5.2 trillion gallons) less than it needs to continue growing at its current pace.

A 2009 McKinsey report on China’s drought estimated that China will need to spend up to $US 3.8 billion (RMB 25 billion) per year nationwide between 2010 and 2030 to counter the effects of droughts and avert agricultural losses. In north and northeast China alone—a market equivalent in GDP to the entire nation of Brazil—up to $US 772 million (RMB 5 billion) will need to be spent annually on reservoirs and dams, drip and sprinkle irrigation, soil conservation, and seed engineering to make crops more resistant to drought.

Food Imports: Made in USA?

Though the recent dry spell is expected to have only a limited impact on economic growth, it is doing nothing to ease the effects of China’s rising price inflation, at 5.3 percent in April, much higher than the government’s target of 4 percent. Meanwhile, national food prices went up by 11.5 percent in April, while non-food item prices increased by 2.7 percent.

Continued food price inflation will encourage more imports, which could help dampen rising domestic prices, analysts say.

While wheat and rice imports haven’t increased much in recent years, China is expected to become a more consistent corn importer year by year. In 2010, China imported a total of 1.5 million metric tons (1.7 million short tons) of corn. Then, in March of this year, China purchased 1 million metric tons (1.1 million short tons) of U.S. corn.

According to the USDA, agricultural exports from the U.S. to China have nearly tripled over the past five years (from $US 6.7 billion in 2005 to $US 17.5 billion in 2010, or RMB 43.4 billion to RMB 113.3 billion). China is now the new top market for U.S. agricultural products, especially soybeans and cotton. The nation is also increasingly acquiring farmland abroad, in places like Brazil and Africa, and steadily importing vegetable oils.

“I think imports will accelerate,” said Lardy, of the Peterson Institute. “China will have to give up and eventually start importing wheat. China cannot keep growing water-intensive wheat in some of the most water-stressed provinces like Hebei and Shandong. Eventually, it will have to give priority to higher-value crops.”

As Circle of Blue reported in April, Chinese farm officials in northern China and academic authorities in Beijing are becoming increasingly concerned that China does not have enough water, good land, and energy to sustain its agricultural prowess.

“I do think that, over time, China will integrate more into the international grain market,” Bunge China’s Lohmar said. “It doesn’t have enough water to continue self-sufficiency policy and continue to grow economically the way it wants to grow economically. Ultimately, it will need to allocate water to higher-value uses.”

Nadya Ivanova—who has reported from China, Europe, and the United States—is a Chicago-based reporter and producer for Circle of Blue. Map by Mark Townsend, a recent graduate of Ball State University’s journalism graphics program. Townsend is a Traverse City-based designer for Circle of Blue. They can be reached at circleofblue.org/contact.

, a Bulgaria native, is a Chicago-based reporter for Circle of Blue. She co-writes The Stream, a daily digest of international water news trends.

Interests: Europe, China, Environmental Policy, International Security.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!