Where Food Grows on Water: Environmental and Human Threats to Wisconsin’s Wild Rice

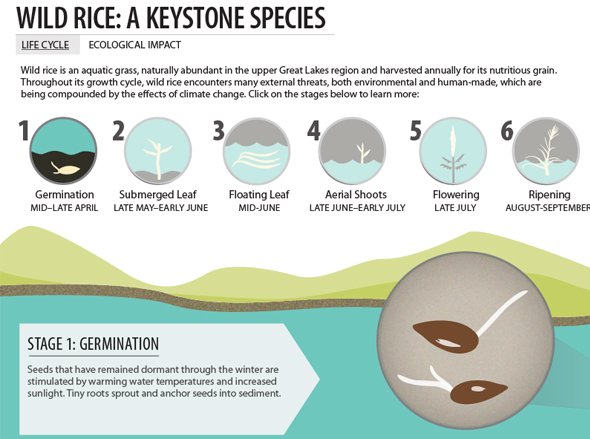

For generations, the upper Great Lakes region has boasted harvests of wild rice, growing in Lake Superior and other watersheds within the basin. But disease, dams, and climate change are now endangering the uncultivated bounty.

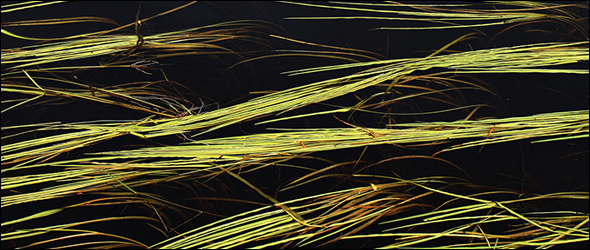

Wild rice on the Bad River Reservation in northern Wisconsin is in the ‘floating leaf’ stage, with a single shoot lying on the water’s surface. This is considered one of the most critical and dangerous stages in the rice’s life cycle, as the stalks are very susceptible to heavy rains and flooding events that can either uproot the plants or drown them. Photo © Codi Yeager / Circle of Blue

By Codi Yeager, Circle of Blue

SANBORN, Wisconsin — In early June, green tendrils of wild rice rise from the Bad River’s soft bottom to take their first breaths of cool Wisconsin air. It is morning, just hours after a storm bent the big pines off the Lake Superior coast and beat the extensive beds of infant wild rice that grow here.

Lisa and Peter David, plant biologists who have dedicated a significant portion of their careers to understanding and protecting wild rice, stand in the wind with arms crossed, surveying this year’s new plants.

“If the lake levels change, we will probably see some rice beds that will cease to exist.”

— Peter David,

Plant Biologist

The Bad River’s rice beds, which later this summer will look like green prairies, perform much as they have for centuries. They provide a stable, supplemental food source for the Anishinaabe people, who hold wild rice as sacred. The rice is also a source of food for wildlife, as well as a habitat for many fish, making it a keystone species for this region’s water-rich landscape.

How much longer that will be the case is not clear, say the Davids. In recent years, climate change has produced stronger storms and more erratic weather. For a plant that grows best in water that is 30 to 90 centimeters (one to three feet) deep, the big changes in water depth caused by heavy rains and floods can drown young rice plants, or pull them out by their roots.

“If lake levels change — getting either higher or lower from where they are — we will probably see some rice beds that will cease to exist,” Peter David says.

The wild rice faces many challenges, both environmental and human-made. First there is the fungal brown spot disease, along with various invasive species such as Eurasian water milfoil and curly-leaf pondweed, which have damaged rice beds in lakes and estuaries throughout Wisconsin; but these can all be controlled.

To the south, where there is more industry, water management practices can cause erratic water levels for energy production, logging, and recreation. These competing human uses, however, have the potential to become the foundation for negotiating solutions to water level problems, which could inadvertently help the rice. But tribal members here worry about pollution, as industry moves northward with a proposal to build a taconite, or low-grade iron ore, mine near the headwaters of the Bad River. And the effects of climate change are like a bad infection, making all of this worse.

Climate Compounds Coastal Rice Problems

The preponderance of scientific evidence — much of it amassed in the land grant research universities of the Great Lakes states — indicate the warming planet could lead to even lower water levels in the Great Lakes. Though, to what extent the levels could change is hard to pinpoint, explained Brent Lofgren, a physical scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

“Our expectations are in a state of flux,” Lofgren said. “One thing that has been observed is a drop in lake levels that was pretty sudden in 1998, and, though there have been fluctuations since then, they have stayed low compared to mean levels. The tricky thing is attributing the changes to greenhouse gases.”

Even a small change in water levels for a plant that prefers water 30 to 90 centimeters (12 to 36 inches) deep can disrupt plant growth and reduce the rice population on a river or in a lake. That is what the Davids, and the Ojibwe nations, who employ them, are working to prevent.

The husband and wife scientific team serve as biologists at the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), a natural resource management agency of 11 Ojibwe nations in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan that is based in Odanah, Wisconsin.

“It is pretty hard to overstate the significance that this plant has,” Peter David says. “Climate change has us really concerned about what that might mean for the rice. Increased heavy rainfall events, flooding that could lead to the plants being uprooted or drowning; it is all a big concern.”

Drowning Due to Storms and Dams

The rice is most vulnerable in June, when it is in the aptly named “floating leaf stage,” a critical time in the growth cycle. The rice grows out from its roots in the very soft bottom sediments, but, during this stage, the rice becomes very buoyant, floating along the surface. Since the root systems aren’t fully developed at this point, if there are high winds or high waves, it is possible that the plants could be uprooted and pulled out of the sediment.

Additionally, during this stage, the rice undergoes a physiological change. Previously, when the rice was wholly submerged under the water, it was exchanging gases with the water column, but, now, it begins to exchange gases with the air. If the rice is then resubmerged — like in a flooding event, for example — the plant could actually drown.

A similar outcome occurs when water levels are intentionally manipulated, and there is no shortage of dams that do just that in Wisconsin.

“The rice beds have definitely declined from historic levels,” Peter David says. “Out of all the rice beds that we’ve lost, most have been due to changes in hydrology. If you look at the Wisconsin River system, it is just dam after dam after dam. In some places dams are operated, there can be a five- or six-foot [two-meter] change in water level over the growing season, and that is more than the rice can tolerate.”

The Davids acknowledge that dams are not inherently incompatible with wild rice, which actually likes some variation in water levels. Properly managed dams can mimic this natural fluctuation and can prove to be good growing regions. Most dams, however, are used to manage water levels so they are suitable for power generation or recreation, instead of for rice habitat.

“People generally like their lake levels high, so they can boat, they can swim, they can get to the open water,” Lisa David explains. “But that water level is too deep for rice.”

“For the wild rice beds to remain present in the coming years, there has to be a continual water level that needs to be respected.”

— Roger LaBine,

Lac Vieux Desert Tribal Member

This was the situation that the Chippewa people of Lac Vieux Desert, a lake which straddles the Michigan-Wisconsin border, faced when the lake was dammed — first for a logging operation and later for power generation.

“When the dam was built at the outflow of Lac Vieux Desert, which is the headwaters of the Wisconsin River, it raised water levels and destroyed the rice beds that were there,” Roger LaBine, a Lac Vieux Desert tribal member, said in an interview with Circle of Blue.

In 2002, in cooperation with the U.S. Forest Service and other partners, the people of Lac Vieux Desert secured a court federal order that required the water levels to be lowered for a test period of 10 years. The order allowed one of the largest wild rice restoration projects in Michigan to begin, and there will be an evaluation of the rice bed in 2012, when the issue, once again, goes before a federal court.

“We got 10 years to grow 70 acres [28 hectares] on the lake, to prove that controlled water levels would allow the rice beds to be restored,” LaBine said. “Last year, we were at 87 acres [35 hectares], and we haven’t reseeded in three years. For the wild rice beds to remain present in the coming years, there has to be a continual water level that needs to be respected.”

Heavy Rains and Fungus: Signs of Climate Change?

Now, rice beds here and elsewhere in northern Wisconsin are subject to the new forces of a warming climate, with consequences potentially more ruinous than human-made dams.

Last year, unexpectedly heavy rains at the beginning and end of the ricing season wreaked havoc on the beds — tearing up young plants during the spring growth period and beating rice out of seed heads during the fall harvest. Along for the ride was fungal brown spot disease, whisking through thick rice stands on the warm, humid air.

Close to where the Bad River runs into Lake Superior in northern Wisconsin, wild rice is in the ‘floating leaf’ stage, when a single thin shoot rests on the water’s surface. By harvest time in late August, the plants are a meter (three feet) tall, and harvesters must bend the stalks over their canoes to gently knock the rice from the seed heads. Photo © Codi Yeager / Circle of Blue

It was one of the worst ricing seasons in the last 20 years. In a good year, more than 45 metric tons (100,000 pounds) of rice can be harvested from off-reservation waters in Wisconsin. Last year saw a meager 7 metric tons (15,000 pounds) of harvest.

“Brown spot disease has been around for a long time, but most years it doesn’t have that big of an impact,” Peter David says. “Last year, you could see the whole color of the beds change because of the infestation, and it really reduced seed production. These are the kinds of things that, yeah they’ve been happening for centuries, but it seems like they’ve been happening more often than they used to. Rice is not a plant that is designed to disperse across the landscape, so when you lose a bed someplace, it might take centuries for rice to recolonize that site. Some plants may be able to move their range more readily to adapt to climate change, but rice probably isn’t one of those.”

So, what if the rice is lost? The Davids tout its ecological importance — a feeding ground for ducks, geese, and swans, as well as a hatchery for fish and a home for mink and muskrat.

To the Anishinaabe people, it is that and more.

Historical Significance for Native American Tribes

“Manoomin: it is a conjunction of two words,” Joe Rose Sr. explains. Rose grew up on Bad River Reservation and is now the director and an associate professor of Native American Studies at nearby Northland College, an environmental liberal arts institution in Wisconsin, just a few miles from the Michigan border. Under his baseball cap, he has white hair and kind eyes. His hands move as he talks. “Mino means something good, and miin is a seed, or berry. We call it Manoomin: the wild rice.”

Sitting at an old conference table in the brick building shared by the tribal headquarters and GLIFWC, the rhythm of Rose’s words is like a quiet melody as he tells the story of his people — how they journeyed first East to the Atlantic Ocean and then followed the signs of the Great Spirit back West, until they found the place where food grows on water.

“[The rice] was declared sacred, because it was a part of the prophecy and played a very important role in the returning home of the Anishinaabe people,” he says.

Rose began harvesting wild rice when he was nine years old; his brother was seven. Wisconsin’s rice harvesting law is based on those traditional harvests, which protected the beds. Harvesters must use a boat no wider than 96 centimeters (38 inches) and no longer than five meters (17 feet). Motors are illegal, and boats are instead pushed through the beds using a wooden pole. Harvesters gather the tops of the plants and dislodge the kernels by whacking them with light wooden sticks.

“We went down to the Kakagon Sloughs all by ourselves,” Rose remembers of harvests with his younger brother. “My grandfather and my parents, they helped us get our equipment together and went to see us off. We’d go down, and there would be native elders down there, so we felt safe. By the time we were teenagers, by the time I was about 18 years old, we were making 300 pounds [135 kilograms] of clean rice a season…[now] the ricing isn’t nearly as good as it was back then.”

Rose has missed only one or two seasons since that first one, and he has seen changes come to the rice beds. He says water levels have a lot to do with it. In 2007, for instance, Lake Superior was about two-thirds of a meter (two feet) lower than the normal average, and that affected the Kakagon Sloughs, where Rose has continued to harvest, with rice growing up out of mudflats instead of knee-deep water.

“For the first time in history, the Bad River Tribal Council closed the ricing season,” Rose says. “And nobody went out.”

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

A good and informative article. However, Yeager failed to mention the man-made threat that copper mining presents to wild rice stands. Unfortunately, there is no specific mention of sulfate and hydrogen sulfide and their destructive effects on wild rice.

We meant to have a few paragraphs about the mining issue, Robert, but we had to do a quick publish to get the story out. However, we have since updated the piece with a sidebar on this issue. We hope that you find this information completes the story. Check out the new sidebar, and thanks for your input!

Very informative but the infographic seem to not be working!