In China, Every Square Meter Counts

Circle of Blue’s senior editor wraps up his first of three weeks reporting in the field from China, finding a wealth of promise in fields of golden wheat.

XINXIANG, Henan Province — The fields of Henan Province, one of the important centers of global wheat production that is located in east-central China, spread beyond this city’s high-rises, a prairie of dusky grain in every direction to the horizon. Every mu — a Chinese measurement of land expanse equal to about 270 square meters (or 7 percent of an acre) — is taken with ripening wheat.

The harvest has begun. Workers cut stalks with long blades and haul the wheat out of the fields on their backs. The streets serve as long, linear threshing tables as farmers spread the straw and seed heads on the just-built broad boulevards, relying on trucks and cars to roll over the piles. Then, with pitchforks, men and women stab hard at the crumbled piles and toss the grain high in the air, the wind carrying the bits of straw away from the seeds.

The streets at this time of year are an inch deep in drying wheat, the color of a dull yellow sun.

The average Henan farm, according to experts I talked to at the Institute of Agriculture here, measures about one mu. That makes Western-style mechanization — with big tractors, big planters, big harvesters — impractical.

But China also hasn’t experienced the rural depopulation of farming families and workers that we did in the American countryside from 1960 to 1985, which essentially drowned one-stoplight towns in a sea of business bankruptcies and empty storefronts.

There are no such empty spaces in rural China.

Men and women scrub the fields clean of weeds by hand. They toss wheat to the wind by hand. They pull vegetables from the fields by hand, stacking greens and tomatoes and corn and squash in the back of three-wheeled electric carts. With their pre-school children standing on the seats beside them, they transport the harvest at dawn to big street markets that are jammed with buyers by 6:00 a.m. The outdoor markets hum with the same high-amp crowd noise that accompanies high school football games in the United States.

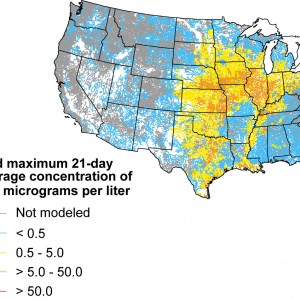

I am here for three weeks to study how the Chinese economy can sustain the high growth rates that have marked its rise to global prominence over the last two decades. Demand for energy and food confronts this nation’s declining reserves of fresh water. The choke point, which we reported extensively on last year, is tightest in Henan and in provinces to the north and west of here.

China’s central government asserts that the nation — already the world’s largest grain producer and energy consumer — can solve its water supply dilemma and simultaneously grow with the immense speed and scale that Chinese citizens and world markets have grown accustomed to.

How to execute that trick is very much a subject of serious consideration and research in Beijing and provincial governments. (And the U.S. economy depends on China’s succeeding to an extent that most Americans will find revealing.)

I like China’s chances. All that grain — tossed to the sky, little brown clouds that for a brief moment look like a swarm of bees scattering from a broken hive — is evidence of a determined and hard-working people that know what it takes to thrive.

–Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue senior editor

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!