The Mississippi Seesaw: Extreme Weather Begets Extreme River Levels

With historic drought following historic floods, the lower Mississippi River basin has seen, in consecutive years, both ends of the hydrological spectrum.

The Mississippi River at Memphis, Tennessee is 17.3 meters (56.7 feet) lower today than it was just 15 months ago during the spring of 2011. Back then, record floods led the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to blow up a levee and flood farmland in Missouri to reduce pressure on the river’s flood control systems and to save upstream cities.

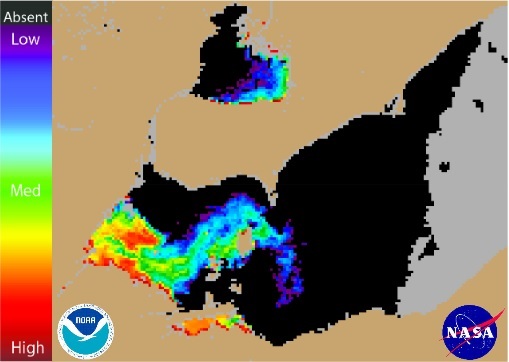

This summer, sections of the Mississippi have swung from all-time highs to all-time lows. For several weeks the Army Corps has been dredging the river bottom to keep navigation channels open. Last Thursday it began building an underwater levee in Louisiana to block a wedge of salt water flowing upstream from the Gulf of Mexico. And in central Mississippi an 11-mile stretch of the river is closed because of low water.

Look at that first number again – nearly 57 feet. A column of water that deep would soak the carpet in a fifth-story apartment.

In a summer of striking weather stories, this simple comparison stands out. There is perhaps no better illustration of the duel challenges of unprecedented surplus and deficit—and rapid oscillation between the two—that water managers now face.

While climate scientists are debating whether specific events in recent years—the Russian heat wave of 2010, the Texas drought of 2011, and the current dry spell in the U.S.—can be attributed to climate change, the fact of the matter is that such extremes are here now. And if climate models are correct, they will become more common in the future.

So Army Corps leaders are rebuilding the Birds Point levee, the one they blew up last year, and holding talks about the future of flood control at the same time that they are digging up the bottom of the river to keep commerce flowing.

And it’s not just the Mississippi River states that should worry. Circle of Blue has just published a package of stories examining the economy and ecology of the Great Lakes region. One element is fluctuating lake levels that are confounding shipping companies, reducing cargo loads and cutting revenues.

What other statistics reveal the bigger picture? Contact Brett Walton

Brett Walton

Circle of Blue reporter

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

This morning I looked at a map of projected rainfall from the hurricane remnants down south, and it looked like an area straddling the Mississippi River all the way up to about Ohio, is forecast to receive nearly a foot of rain in the next two or three days. I wonder what impact this might have, since the river is so low now. Might this rain cause a surge in the river? Would a large amount of silt and sediment be expected to wash out into the Gulf? And would there be stretches which might experience significant changes in morphometry?