Florida Oyster Harvest Suffers As Drought Intensifies Water Battle with Georgia and Alabama

The drought that set upon the United States this year has tightened a three-state tug-of-war over fresh water, affecting marine life and a valuable fishing economy downstream in the Deep South’s Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin, the most biodiverse river system in North America.

By Codi Yeager

Circle of Blue

EASTPOINT, Florida — The afternoon sun turns the sky white as the boat bobs on the bay’s blue waters. Shannon Hartsfield, a fourth-generation oysterman and president of the Franklin County Seafood Workers Association, balances on the gunwale and scissors a four-meter (14-foot) pair of tongs along the oyster bar below. He heaves them up, depositing the catch onto a wide culling board across the bow. Only a handful of harvestable oysters can be separated from the pile of mostly empty white shells.

“We are having a lack of product, and we are not able to provide for our families like we should because of the drought,” says Hartsfield, who grew up on the Apalachicola Bay. “We’re the last on the totem pole when it comes to fresh water, and we get whatever we get — and there’s been a lack of it [this year].”

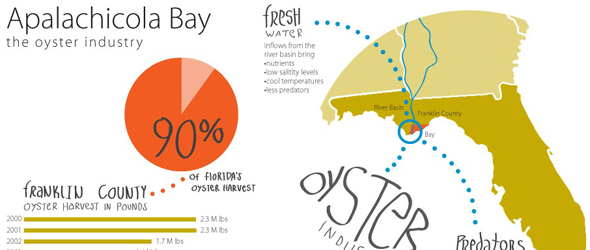

The bay is the last stop for the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) River Basin, an expanse of estuary marshes, sea-grass beds, and oyster bars hemmed in by shifting barrier islands in the Gulf of Mexico. The ecosystem in the bay relies heavily on freshwater flows from the Apalachicola River. Ten percent of the aquatic area of the estuary is covered in oyster bars that provide 90 percent of Florida’s annual oyster harvest. But this has been a particularly difficult year. The ACF Basin, buffeted by natural drought this year, also contends with growing demands for water in the three southeastern states that share its waters.

The combination of dry weather and scarce water, prompted by one of the basin’s worst droughts on record, is both a striking symptom of the endemic problem that more than half of the continental United States faces this year and a test of human resolve to solve penetrating rivalries that are putting the economy and ecology of this region in jeopardy. Indeed, say authorities and scholars, the drought facing this southeastern corner of the country highlights the need for thinking much differently about managing water supplies and sharing rivers — something a 22-year-old court battle between Alabama, Florida, and Georgia has failed to deliver.

From its headwaters in northern Georgia down to where it drains into the Gulf of Mexico, the 51,000-square-kilometer (19,800-square-mile) ACF Basin provides fresh water to around 4 million residents in the Atlanta metropolitan area. It also supports Georgia’s $US 2.4 billion bread basket and is used by hydroelectric, nuclear, gas, and coal-fired power plants in Alabama, Florida, and Georgia. Moreover, the ACF Basin supports the most biodiversity of any river system in North America, and, when it at last spills out into Florida’s Apalachicola Bay, its nutrient-rich freshwater plume extends 400 kilometers (250 miles) into the Gulf, providing commercial fishing grounds for oysters, grouper, snapper, crab, and shrimp.

Worst Drought On Record?

The three states have been embroiled in litigation that is centered around Atlanta. Georgia wants to use Lake Lanier, a reservoir managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, to meet the growing city’s municipal water needs, while Alabama and Florida argue that this is not an authorized use of the reservoir’s water.

In years with plentiful rain, there is enough water for all. But a severe drought in 2007 revealed just how vulnerable the river system is to dry weather. This year, the region is again headed for tight water times.

“We are going into drought earlier this year,” Lisa Coghlan, deputy public affairs officer at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Mobile District, told Circle of Blue. “We didn’t receive the spring rains like we usually do.”

The Corps is required to release enough water to maintain certain stream flow rates in the Apalachicola River, but, because there are no water impoundments on the Flint River, the majority of water flows must come from the Chattahoochee, Coghlan explained. With little rain and lingering dryness from the 2011 La Niña, virtually all of the flows are coming from the Chattahoochee, while water levels in the Flint are dropping to near historic lows.

In May, the Corps began working under drought operations, which reduce the amount of water the Corps is required to release into the Apalachicola River to 127 cubic meters per second (4,500 cubic feet per second). Despite periods of rain over the summer, much of the ACF Basin is still experiencing exceptional drought conditions — and the region missed out on rains from Hurricane Isaac that could have replenished the system.

The Corps is currently releasing about 141 cubic meters per second (5,000 cubic feet per second) into the river from Jim Woodruff Dam on Lake Seminole. Flows on the river can be between 2,265 and 2,831 cubic meters per second (80,000 and 100,000 cubic feet per second) during a normal year, and should be at 198 cubic meters per second (7,000 cubic feet per second) even during a drought, Dan Tonsmeire, the executive director of the Apalachicola Riverkeeper, told Circle of Blue. But overuse of water in the ACF is pushing the river to its limits.

“We’ve lost somewhere between 30 to 40 percent of the flows that we should be having right now, so the river should be at least another 30 percent higher,” Tonsmeire said. “We may be in the worst drought on record here, as far as looking at river flows and groundwater levels. It may not be the worst drought in terms of rainfall, but, because there is so much water being sucked out of the Chattahoochee and the Flint for municipal, industrial, agricultural, and energy type uses, all of that bears a burden on the Apalachicola in these low water times.”

Those upstream users — including Atlanta residents, Alabama power plants, Georgia farmers, and others — must dole out enough water to meet the Apalachicola’s environmental flow requirements, leading to tensions between users on the Flint River and those on the Chattahoochee. Meanwhile, Florida argues that the flows are not enough to sustain the river’s endangered species or the seafood industry in Apalachicola Bay.

Bad for Florida Oyster Industry

While the three states fight in court, stakeholders who depend on the river — like Shannon Hartsfield does — are struggling to make a living. One of the areas that is most threatened by the current drought is Apalachicola Bay, which supports a $US 134 million commercial seafood industry, with an additional $US 71 million in value-added benefits each year. Historically, the bay has accounted for 60 to 85 percent of employment in surrounding Franklin County, Florida, according to a report from the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve (ANERR).

But there have not been many oysters to catch, process, and sell this year.

Successive years of drought have stressed the bay’s oyster population so much that some bars are unlikely to be able to sustain harvesting during the 2012-13 winter harvesting season, according to findings from Florida’s Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (DACS).

–Lisa Coghlan

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

In some areas, oyster populations decreased from 430 oysters per square meter (40 per square foot) in 2011 to 64 oysters per square meter (6 per square foot) this summer — an 85 percent drop. The DACS rated the overall outlook for oyster production this winter as “poor,” prompting Governor Rick Scott (R-Florida) to send a letter earlier this month asking the U.S. Department of Commerce to declare a commercial fishery failure in the bay, which would unlock disaster relief funds.

Oystermen working the bay are allowed twenty 27-kilogram (60-pound) bags of oysters each day. In a good year, they can catch that amount, Hartsfield says, but now eight or nine bags is considered a good haul.

“Since 2005, it’s just going downhill,” he says. “2007 was terrible; it was one of the worst years that we’ve had. Right here, in 2012, we’re looking at another year that bad.”

One of the culprits is high salinity in the bay, due to less freshwater flows coming in from the Apalachicola. High salinity allows salt-loving oyster predators like crown conchs, southern oyster drills, stone crabs, and boring clams to wreak havoc on the oyster bars.

“That stops the predators from coming in, when we have fresher water,” Hartsfield says. “Even in our typical year, we have some come in — but we’ve never experienced what we have coming in now. We’re having bars completely wiped out because of too many conchs. You can’t even go make a living.”

But predation is not the only problem. Additionally, because they have been denied the flow of nutrients coming from the Apalachicola that helps them to grow, the oysters are not reviving.

Typically, an oyster in Apalachicola Bay can grow from its larval stage, called spat, to a harvestable size greater than eight centimeters (three inches) within 39 weeks, if conditions are right, according to the ANERR report. It is one of the fastest growth rates for oysters in the United States, but droughts slow down the process.

–Shannon Hartsfield, president

Franklin Seafood Workers Association

“Usually you work an area for about a month, and you move away and work another area. Back and forth. But usually by the time you’ve worked a month in another area, you can come back to that area and little ones would be growing,” Hartsfield says. “We’re not getting the growth on them anymore, because we don’t have the nutrients.”

And it is not just oysters that are suffering from lack of freshwater flows into the bay from the drought — since 90 percent of all fish, shrimp, and crab species that are harvested commercially in the Gulf of Mexico spend some portion of their lives in estuarine habitats like Apalachicola Bay, this region is also an important nursery ground for those aquatic species. Adult blue crab, for example, travel hundreds of kilometers offshore to spawn before their young return to the shelter of the bay to mature. Mullet and flounder, as well as white, pink, and brown shrimp also call the bay home.

Water Management Threatens Interwoven Ecosystem

To find the missing nutrients, one must trace the river up to its floodplain, where the winter and spring floods account for up to 50 percent of the annual flux of total nitrogen and phosphorous into Apalachicola Bay. In late May, the effects of the ACF’s thousand straws are readily apparent.

The 400,000-hectare (100,000-acre) floodplain is largely dry, and the steep clay banks dropping from the forest to the main river are baked hard. Water flows in the river have slowed to 127 cubic meters per second (4,500 cubic feet per second), cutting off natural sloughs that divert water from the Apalachicola River into floodplain swamps, shaded by tupelo and cypress trees.

Before 2007, this channel was never cut off from the river. Now, however, it has been reduced to a few scattered puddles.

“The main river channel is connected to the floodplain, and the backwater swamps back there are where the biodiversity is — the habitat for fish, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and mammals, as well,” says Dan Tonsmeire, executive director of the Apalachicola Riverkeeper, as he navigates the boat close to the outer banks of the main river, where the water is deepest. “The importance of it being inundated part of the year during the flood cycle, and at least connected during the low water times, is critical to that whole function staying alive and sustained.”

The floodplain is the largest in Florida, and it can stretch 7.2 kilometers (4.5 miles) across when high flows — as much as 8,495 cubic meters per second (300,000 cubic feet per second) — charge down the river.

Of the 1,000 species of plants growing here, over 70 are trees and 22 are endangered, according to the ANERR report. The forest and its meandering waterways provide habitat for 44 species of amphibians, 64 species of reptiles, and 60 species of snail and clams, of which seven are endemic. River otters, beavers, and migrating birds also call the floodplain home. When it is inundated, fish — there are 131 species in the ACF Basin — move out into the forest to forage and spawn.

This intricate system can withstand natural droughts, but water management in the Basin is drying out the floodplain for increasingly long periods of time, Tonsmeire explains.

“From an ecosystem perspective, everything is under stress in the normal course of a drought, and what we’re doing to them now is we’re intensifying that stress level for a much longer period of time,” he says.

To illustrate his point, Tonsmeire pulls the boat towards a small cove on the riverbank. The hull slides into the sand, and he jumps out to tether the vessel to a protruding stick. His dog, Sage, bounds ahead down the dry bed of Swift Slough.

–Dan Tonsmeire, executive director

Apalachicola Riverkeeper

The channel had never been cut off from the river before 2007. That year, a population of 20,000 endangered fat three-ridge mussels was completely wiped out when the Army Corps of Engineers dropped water flows to 127 cubic meters per second (4,500 cubic feet per second), disconnecting the slough for almost six months. The mussels, as well as the Chipola Slabshell and the Purple Bank Climber mussels, are protected under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), but the Corps was able to get a waiver, due to the drought.

A recent biological opinion released by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Commission, which enforces the ESA, stated that the Corps will once again be able to drop water levels to 127 cubic meters per second (4,500 cubic feet per second) as part of its drought procedures. The opinion concluded that reduced flows will “not jeopardize the continued existence” of the three mussel species, but also that “lower flows for longer durations will negatively impact all three mussel species.”

Tonsmeire is skeptical about the opinion, however, and is a strong advocate for restoring higher river flows on the Apalachicola before the unique ecosystem is irrevocably changed.

“Over time, your whole hydrology starts to change, and we’re just in the early stages of seeing that happen,” he says. “So that’s why it’s such a critical thing for us to try to reverse this trend of continually less and less flow coming down here — either from people taking it out and using it up or from the way the Corps is managing the system. They’re actually changing the hydrology when they’re filling their lakes, and at the time when we need to be getting the water. It’s throwing our cycle off.”

Water Use Increases, While Drought Shrinks Supplies

Droughts can compound water-management problems, as private citizens use more water for watering lawns and power stations need more water to cool their electricity-generating plants. Moreover, water use in Georgia’s agricultural sector can jump from 643 million liters a day (170 million gallons a day, equal to 7.3 cubic meters per second or 260 cubic feet per second) to more than 2.4 billion liters a day (650 million gallons a day, equal to 28.3 cubic meters per second or 1,000 cubic feet per second ) during a drought, according to a report prepared by the Congressional Research Service (CRS) in 2008.

Much of this use is concentrated in the Flint River sub-basin, where agricultural production is worth about $US 2.4 billion. Agriculture accounts for 90 percent of annual water withdrawals in the Flint Basin, mostly from aquifers that are connected to surface water, according to the CRS report.

Unlike the Chattahoochee, the Flint River has very few dams and little water-storage capacity. So when drought creates a spike in withdrawals from the Flint, the Corps of Engineers has to meet nearly all of the environmental flow requirements for the Apalachicola by releasing more water from reservoirs on the Chattahoochee, pitting upstream users in the Atlanta area against farmers in the Flint Basin.

The farmers risk seeing their fields and pocketbooks dry up without irrigation, but recognize that their use — there are approximately 6,700 center pivot irrigation systems in the Lower Flint Planning District — places a burden on downstream stakeholders, like Hartfield and his oysters.

“It is extremely important for our region because it is an ag-based economy, and our reliance on fresh water is really what drives our economy,” Mark Masters told Circle of Blue. Masters is the director of projects at the Georgia Water Planning and Policy Center at Albany State University. “I think it is important to keep in mind that the rank-and-file farmers have done a pretty good job of conserving where they can. On the other hand, when we’re having the conditions like we’re having now with the drought — into the second year of the drought — we certainly impact the resource with as much irrigation as we use.”

–Mark Masters

Executive manager of ACF Stakeholders

Georgia Water Planning & Policy Center: Albany State University

Masters is also the executive manager of the ACF Stakeholders — a group including both Tonsmeire from the Riverkeeper and Hartsfield— that has come together to resolve water-management issues in the Basin in the absence of state leadership.

“We’ve got 56 stakeholders from throughout the Basin — interests ranging from seafood and navigation to production agriculture to big municipalities and everything in between,” Masters said, explaining the ACF Stakeholders organization. “There’s no question that all of the stakeholders in the ACF, from top to bottom, are all interconnected. The agricultural sector, the people around where I live in southwest Georgia, understand that they are part of this system, and they want to come to the table with solutions to figure out how we can best share the limited resources that we have. I think they want to see a solution after 20-plus years of litigation and fights among the states.”

For the farmers, the oystermen, and the conservationists like Dan Tonsmeire — whose love of the river is clear when he drops his voice respectfully as the boat floats silently down a glassy tributary — there is no choice.

“It has to be resolved, or it’s going to kill us off down here,” he says. “Our economy, our tourism, our seafood industry are all dependent on this ecosystem.”

Read more about the tri-state battle here. Read more about the 2012 U.S. drought here.

Alec Aja is an undergraduate student at Grand Valley State University and a Traverse City-based design intern for Circle of Blue. Reach him at circleofblue.org/contact

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

Please note that the Apalachicola Estuarine Research Reserve report that you reference in this article is based only on data up to 2007, so really is not a good current reference. We would like to see some interim data and detailed explanations, but they are not forthcoming. Why did the Bay experience high reported landings of oysters in 2009, for instance, after two years of drought? Blaming it on drought alone, as your article and headline suggests, is over simplistic. But this probably serves your agenda, and the Riverkeeper agenda as well, so I guess we should not expect thorough journalism, just like we have come not to expect thorough resource management from DACS or ANERR. When oyster-harvesting licensee numbers double in four years and bags per landing is cut by a third, the handwriting is on the wall, and it says, “Over-harvest is a big factor in this depletion event.” And there are, no doubt, a complex of other interacting factors, such a tropical storms that also have a hand in this. To fail to acknowledge this degrades this “reporting” to the level of propaganda.

I agree with this comment 100%. Oysters have survived the weather for hundreds of years. At what point are we going to hear about testing for possible chemicals that could be a factor? I’m tired of my intelligence being insulted by the media and would like some facts instead of speculation. How long are we to let this situation “run it’s course”?

After the oil spill, harvesting of sub-legal oysters became more…. acceptable. It was feared that if the oysters weren’t harvested they would be lost. This practice has continued even after the threat was gone. The DACS report gives more information. It can be found here:

http://www.wtxl.com/media/lib/159/1/4/f/14fb19a1-ec3c-4f8e-ac51-881d20da5884/09_06_2012_Declaration_Request_Gov_Letter.pdf