Fossil Fuel Boom Shakes Ohio, Spurring Torrent of Investment and Worry Over Water

Ohio’s shale oil and gas fortunes point up.

By Keith Schneider and Codi Yeager

Circle of Blue

WELLSVILLE, Ohio — A torrent of investment in mineral leases, manufacturing plants, pipeline construction, and drilling platforms signals what business executives and state energy officials say is the most significant surge in Ohio’s oil and gas development in decades.

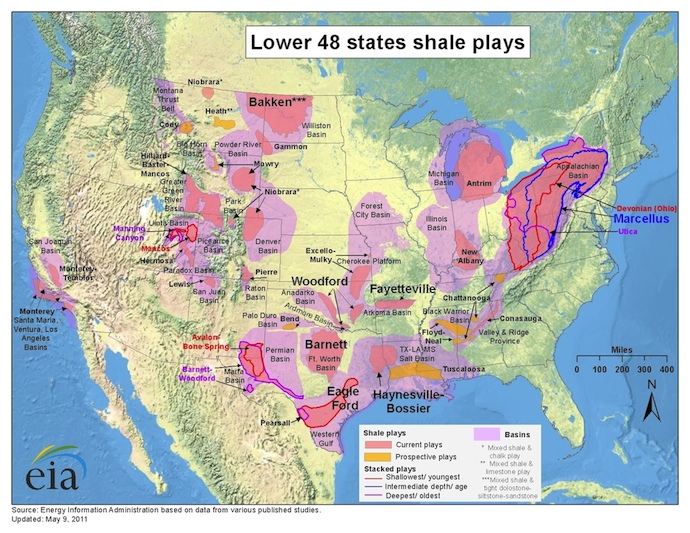

But the development of the Marcellus and Utica shales, two hydrocarbon-rich rock layers beneath much of eastern Ohio, also is producing fresh public concerns about the consequences to public safety and to the state’s waters from the disposal of millions of barrels of contaminated oilfield wastewater.

On Friday, the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) imposed tough new regulations on the operators of the state’s 177 deep-injection wastewater disposal wells. The new rules, prompted by earthquakes last year that were centered around a year-old injection well in Youngstown, will make Ohio’s Class II deep-injection wells among the most stringently monitored and regulated in the nation.

The other features of the new taxonomy of energy development span the promise of big job growth and the peril of inadequate oversight, and they are on display in and around this Ohio River Valley town of 3,800. Plans to build a $US 6 billion coal-to-liquid-fuels plant on a bluff above Wellsville were modified last fall in favor of a $US 3 billon gas-to-liquids (GTL) plant that would use natural gas to create 50,000 barrels (2.1 million gallons) of diesel and naphtha fuel each day. The switch is breathing new life into the project, which has struggled for four years to secure funding.

Total SA, France’s largest oil company, announced just after the start of the year that it had paid $US 2.32 billion to Chesapeake Energy Corp. and EnerVest for 250,500 hectares (619,000 acres) of mineral rights in northeastern Ohio. Natural gas companies are offering landowners in Wellsville and the surrounding communities up to $US 5,800 an acre for mineral leases.

–Rick Williams

Wellsville resident

Royal Dutch Shell announced this week that its favored site to build a multi-billion-dollar plant to convert natural gas to ethylene is in Pennsylvania, about 20 miles north of here.

“We are now assessing various possible longer-term options to use domestically abundant natural gas in new ways, extending its application beyond current industrial and residential uses, and as a fuel to make electricity, including a natural-gas-to-liquids facility in the U.S.,” Kayla Macke, media relations coordinator at Shell Oil, wrote in a statement to Circle of Blue.

Chesapeake Energy — by far the largest investor in the Utica and Marcellus shale development in Ohio — announced in November that its production would anchor a 1,980-kilometer (1,230-mile) pipeline from Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and northeastern Ohio to the Gulf Coast. The pipeline would have an initial capacity of 125,000 barrels per day of ethane, the company said in a news release.

Chesapeake this week announced plans to join with several partners to build a gas processing plant here in Columbiana County, another in Harrison County south of here, and transport and storage infrastructure valued at $900 million. MarkWest Energy Partners, a Denver company, said earlier this year it will build a processing plant in Harrison County, and another in Monroe, downriver, in projects valued by JobsOhio, a development organization, at $500 million. Two more companies — NiSource and El Paso Corporation — also are interested in building gas transport and processing facilities in the state, David Mustine, general manager of JobsOhio, told Circle of Blue.

“We have a rapidly changing landscape when it comes to energy in Ohio right now,” Mustine said in an interview.

The state’s steel industry also is reviving to produce pipes and equipment for oil and gas production and transport. More than 400 workers in Youngstown are constructing a $US 650 million steel mill for Vallourec & Mannesmann Holdings, Inc. The mill will produce half a million tons annually of seamless steel well-tubing used in drilling and in developing natural gas wells. U.S. Steel spent $US 100 million to expand and upgrade its tubular steel mill in Lorain, Ohio, and Timken Company is spending $US 260 million to expand its Canton mill in northeastern Ohio.

Evidence of the rapidly improving mood of this part of the Ohio River Valley is emerging daily. Hotels and motels are full. Winding down one of the country roads outside of Wellsville reveals a shiny new Camaro in the driveway of a farmhouse — the only bright spot on a wet winter day.

“That Marcellus Shale that’s coming around here — that’s making a lot of people around here instant millionaires,” said Rick Williams, a lifelong Wellsville resident who serves as the town’s zoning commissioner. “People are so glad to see this. I mean, we need something, that’s for sure, and between the Marcellus Shale and this gas plant, I think the two will go good together.”

Ohio is no stranger to fossil fuel production. The state brags that the first oil well in the U.S. was drilled in 1814 in Noble County, about 160 kilometers (100 miles) southwest of here. In 1896, with 24 million barrels brought to the surface that year, Ohio was the top petroleum-producing state. John Rockefeller’s Standard Oil refineries in Cleveland and other cities made him the richest man in the world in the early 20th century.

Oil production has steadily fallen in the decades since, except for a brief burst in the mid-1980s. In 1985, Ohio produced 15 million barrels, a modern peak, according to the Ohio Oil and Gas Association. The state’s more than 60,000 wells produce natural gas, in addition to oil. Production peaked in 1984 at 186.5 billion cubic feet, said the association.

In the last two years, though, Ohio’s Marcellus and Utica shale reserves have awakened the industry.

Natural gas production in Ohio last year climbed to roughly 80 billion cubic feet, a 3 percent jump from 2010, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), a unit of the federal Department of Energy. Oil production climbed to 5 million barrels, a 4 percent increase from 2010.

Water Use in Hydrocarbon Shales

State and federal geologists say the Marcellus formation contains trillions of cubic feet of natural gas. They also estimate that the bigger and deeper Utica Shale holds trillions of cubic feet of gas, along with billions of barrels of recoverable oil.

The state counts more than 130 permits issued since last summer to developers for drilling into the Utica Shale. Five wells are completed, and industry executives say all five are producing large quantities of oil or gas.

The oil and gas sector is tapping the deep shale resources with two well-understood drilling techniques — directional drilling and hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. With the former, companies drill down to the depth of the shale, turn the drill bit sideways and then keep drilling horizontally through the shale for nearly a kilometer (a mile or two). When the basic depth and length of the well is completed, drillers insert a pipe that holds a string of explosive charges along the horizontal reach that blow holes through the metal.

The next step, hydro-fracking, involves pumping 15,000 to 23,000 cubic meters (4 million to 6 million gallons) of water — containing both chemicals and millions of pounds of sand — down the well at pressures exceeding 48 megapascals (7,000 pounds per square inch). The torrent erupts through the holes, pulverizes the shale, and produces cracks and spaces that are kept open by the drilling sand. Production starts after 20 to 40 percent of the fracking fluids are drained from the well and brought back to the surface.

But drilling wells that deep is risky. In May 2011, Chesapeake Energy agreed to pay a $US 900,000 Pennsylvania state fine for methane gas that had migrated into residential wells in Bradford County, where the energy company is developing new deep shale gas wells. In December, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which is preparing a study on the risks of fracking on drinking water, found evidence that the high-pressure and chemically intensive production practice had contaminated groundwater in Wyoming.

Disposing of a Flood of Wastewater Creates Quakes

For the time being, Ohio’s most significant concern is how to dispose of the fracking fluids, which are contaminated with chemicals, lubricants, and brine.

State geologists recorded 11 earthquakes around a popular waste disposal well in Youngstown, including a quake on New Year’s Eve that swayed homes. Larry Wickstrom, the chief of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources geology division, told a Youngstown meeting in January that, if the injection well caused the earthquake, it was an isolated incident.

“There is no other place in the state where we see causation from these Class II wells,” Wickstrom said.

Because hydro-fracking uses so much more water than conventional oil and gas production, developing the state’s deep shale resources will increase the amount of wastewater from Ohio’s energy fields. Disposing wastewater from the oil and gas fields of Ohio — and other oil and gas producing states — is no small undertaking.

A 2009 study by Argonne National Laboratory found that drilling and preparing wells for production generates 9.5 million cubic meters (2.5 billion gallons) of wastewater daily across the nation. Ohio energy developers produced almost 2,385 cubic meters (630,000 gallons) daily, according to the study, or 1.1 million cubic meters (or nearly 300 million gallons) annually.

Much of the fracking wastewater in the mid-Atlantic is disposed of in deep-injection wells. In 1990, the Interior Department found, in a report to the EPA, that disposing industrial wastewater in deep wells could cause earthquakes. The report identified five instances of earthquakes centered around disposal wells, including one in 1967 at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal.

In recent months, authorities in Arkansas and Texas also have identified earthquakes around fracking wastewater disposal wells. Southern Texas experienced a 4.8 magnitude earthquake in October 2011 near the Eagle Ford Shale play, which is home to many disposal wells. There have been other earthquakes linked to injection wells in the Barnett Shale.

When earthquakes began occurring in Arkansas in 2010 and 2011, the state Oil and Gas Commission banned wastewater disposal wells within a 1,150-square-mile (2,980-square-kilometer) area north of Conway in the Fayetteville Shale region. According to the Arkansas Geological Survey, the new injection wells were being installed on top of an active fault line.

History of Youngstown Injection Well

The Youngstown injection well opened in December 2010 to serve a growing market for industrial wastewater disposal caused by the natural gas boom in neighboring Pennsylvania. Though natural gas producers in Pennsylvania say they recycle 70 percent of the frack water they use, that still leaves tens of millions of gallons to dispose safely. Pennsylvania has six deep-injection disposal wells. Ohio has 176 operating disposal wells. Companies want to install more of them.

D&L Energy Group, a Youngstown energy producer, recognized a market opportunity. Their Youngstown disposal well on Ohio Works Drive was one of the state’s newest. Soon after it opened, residents began reporting small earthquakes. The ODNR, which issued the permit under regulations and guidelines that had been updated in 2010, investigated and eventually counted 11 earthquakes in 2011 in the vicinity of the well.

Last Friday, state regulators formally concluded that the Youngstown wastewater disposal well was responsible for the quakes. The agency issued a host of new regulations for installing, operating, and monitoring deep wastewater disposal wells.

Economic Promise

Here in Wellsville, residents said they were comfortable with such risks. One reason is the outlook for more good jobs in energy production. The other is that the new burst of natural gas production in the region has reduced the environmental risks of the town’s proposed liquid fuels plant.

A jobs analysis by EMSI, an Idaho-based labor market research group, found that the number of jobs in Ohio’s oil and gas producing sector reached 12,646 last year — 10 percent, or 1,131 jobs, more than in 2005. The average wage of the new jobs was $US 76,000.

The oil and gas industry estimated in a recent study that it would support 200,000 jobs and pour $US 14 billion into the state’s economy over the next four years. Mark Partridge, the Swank Professor of Rural-Urban Policy at the Ohio State University, is skeptical.

— Douglas Southgate, co-director

Subsurface Energy Resource Center

Ohio State University

“We have to be realistic about it,” he said in an interview. “Industries say, ‘We should get special treatment because we will create this supply chain,’ but it is much less than what they say. We are living in a global world. Yes, there will be jobs, but they are going to be spread out over the world.”

Douglas Southgate, co-director of the Ohio State University’s Subsurface Energy Resource Center, said lower energy prices from natural gas abundance will ripple through the state’s economy. He joined the authors of a PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) study released in December that reported on how 17 major American manufacturers in 2011 had told the Securities and Exchange Commission that natural gas abundance is dramatically changing their strategic outlook.

Low prices for natural gas are expected to “spark a U.S. manufacturing renaissance over the next few years,” said the PwC study, “boosting revenue and driving job creation.” The firm estimated the shale gas boom alone “could lead to approximately 1 million more manufacturing jobs by 2025.”

“The biggest impact of this development will be to increase energy supplies,” Southgate said. “In Ohio, gas prices should fall, mainly because it will no longer be necessary for gas providers to cover the expenses of bringing in supplies from other parts of the country, and there should be downward pressure on electricity prices as well.

“The benefits of shale development, in terms of energy supplies that are economical, reliable, and cleaner than the alternatives cannot be denied, for Ohio and for the country as a whole.”

Natural Gas Revives Wellsville’s Fuel Plant

One example of the relative environmental and economic benefits of substituting natural gas for coal is right here in Wellsville. The big fuels plant that has been in the works here would have used coal as the feedstock for making liquid transportation fuels. Using natural gas instead would cut carbon dioxide emissions about 50 percent and will reduce sulfur dioxide emissions by 90 percent. The reductions were the primary reason that the Sierra Club and the Natural Resource Defense Council (NRDC) agreed last year to drop legal challenges against the plant’s pollution permits, bringing new hope that construction will proceed.

“No amount of air pollution is good, but this puts it in ranges that we are comfortable with,” said Nachy Kanfer, the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal Campaign Midwest representative.

The project, previously proposed by Baard Energy, is now being developed by Planck Trading Solutions LLC, a group based out of Boca Raton, Fla. Baard’s former vice president of development, Stephan Dupoch, holds the same position at Planck.

The Sierra Club and NRDC are monitoring the project. “We expect it will not be built,” Kanfer said. “It is nothing more than an idea right now. Baard and the various companies involved have shown that they do not have the expertise to lock down financing.”

The plant site is a stretch of forested hills and hollows overlooking Wellsville and the Ohio River. Wellsville’s mayor, Joe Surace, sees the situation differently. “From what we’ve heard, the project is moving forward at a quick pace,” he said.

Codi Yeager reports from Morgantown, where she is a student at West Virginia University.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Comments are closed.