National Security Assessment: Water Scarcity Disrupting U.S. and Three Continents

In a new report, the U.S. State Department finds a global confrontation between growing water demand and shrinking supplies, in addition to predictions for the next 30 years of water security.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

The world’s demand for fresh water is growing so fast that, by 2030, agriculture, industry, and expanding cities on three continents will face such scarce supplies that the confrontation could disrupt economic development and cause ruinous political instability, according to the first U.S. cabinet-level report on the global water crisis.

The report, “Global Water Security,” prepared for the State Department by the National Intelligence Council, found that, unless there are serious changes in conservation and water use practices, global water demand will reach 6,900 billion cubic meters (1,800 trillion gallons) annually by 2030, a figure that is about 2,400 billion cubic meters (634 trillion gallons) higher than today. The authors of the report concluded that level of consumption is “40 percent above current sustainable water supplies,” and will “hinder the ability of key countries to produce food and generate energy, posing a risk to global food markets and hobbling economic growth.”

In other words, this would be the equivalent of adding four Chinas over the next 18 years, since China currently uses around 600 billion cubic meters (158 trillion gallons) of water annually.

These and other findings about global water supply were made public on World Water Day, March 22, by U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who called the study “a landmark document that puts water security in its rightful place as part of national security.”

“It’s not only about water,” she added. “It is about security, peace, and prosperity.”

But those goals are imperiled, according to the report, by the collision of two powerful global trends. The first is what the report called “key drivers of rising freshwater demand” — population growth, expanding cities, rising energy demand and production. The second is declining supply caused by deforestation; pollution; leaks and waste; and climate change that is melting glaciers, speeding evaporation, deepening droughts, and increasing the number of extreme weather events.

In remarks at the World Water Day event in Washington, D.C., Clinton introduced a new government initiative to improve global water management and conservation, steps that the report’s authors repeatedly called for in the study. The U.S. Water Partnership, she said, brings together 28 organizations — including government agencies, philanthropic foundations, environmental groups, corporations, and universities — and their body of water knowledge, which will be spread globally through training sessions, web-based data libraries, and collaborations with any organization looking for solutions.

“You can’t work on water as a health concern independently from water as an agricultural concern,” Clinton said. “And water that is needed for agriculture may also be water that is needed for energy production. So we need to be looking for interventions that work on multiple levels simultaneously and help us focus on systemic responses.”

What The Report Says

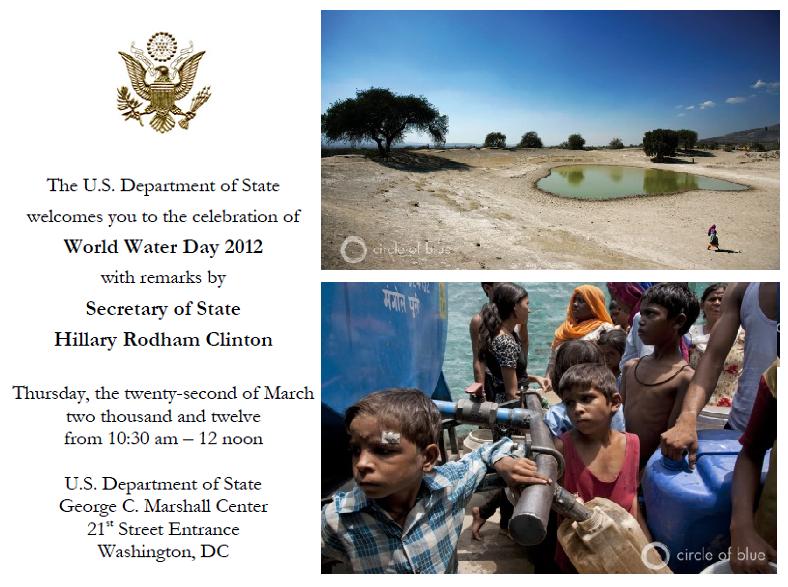

The Global Water Security report confirms much of the data about the severity of the world water crisis, as well as many of the conclusions about how to solve it that have been developed by research groups, by other lower level U.S. government offices, and by news organizations — among them Circle of Blue, whose photographs of the crisis from around the world were featured at the State Department event.

But, in conducting the first cabinet-level assessment and in personally announcing the results, Secretary Clinton continued the work she has undertaken since joining the Obama administration to elevate the threats to the water supply to an urgent national and diplomatic priority.

The United States itself is certain to be buffeted by the water crisis, according to the report, which cites extensive research on food and energy production, groundwater abuse, and trade economics, as well as studies on international conflict and water management practices. For instance, achieving U.S. foreign policy goals could be more difficult, since nations may be too “distracted” by domestic problems to work with other nations. Additionally, there are risks of instability, increased regional tensions, and perhaps even state failure in nations that are important to U.S. national security interests. Water shortages could inflame pre-existing social and political tensions; they could cause disease outbreaks; and they could threaten food security, energy production, and the stability of local economies.

“Water shortages, poor water quality, and floods by themselves are unlikely to result in state failure,” the report says. “However, water problems — when combined with poverty, social tensions, environmental degradation, ineffectual leadership, and weak political institutions — contribute to social disruptions that can result in state failure.”

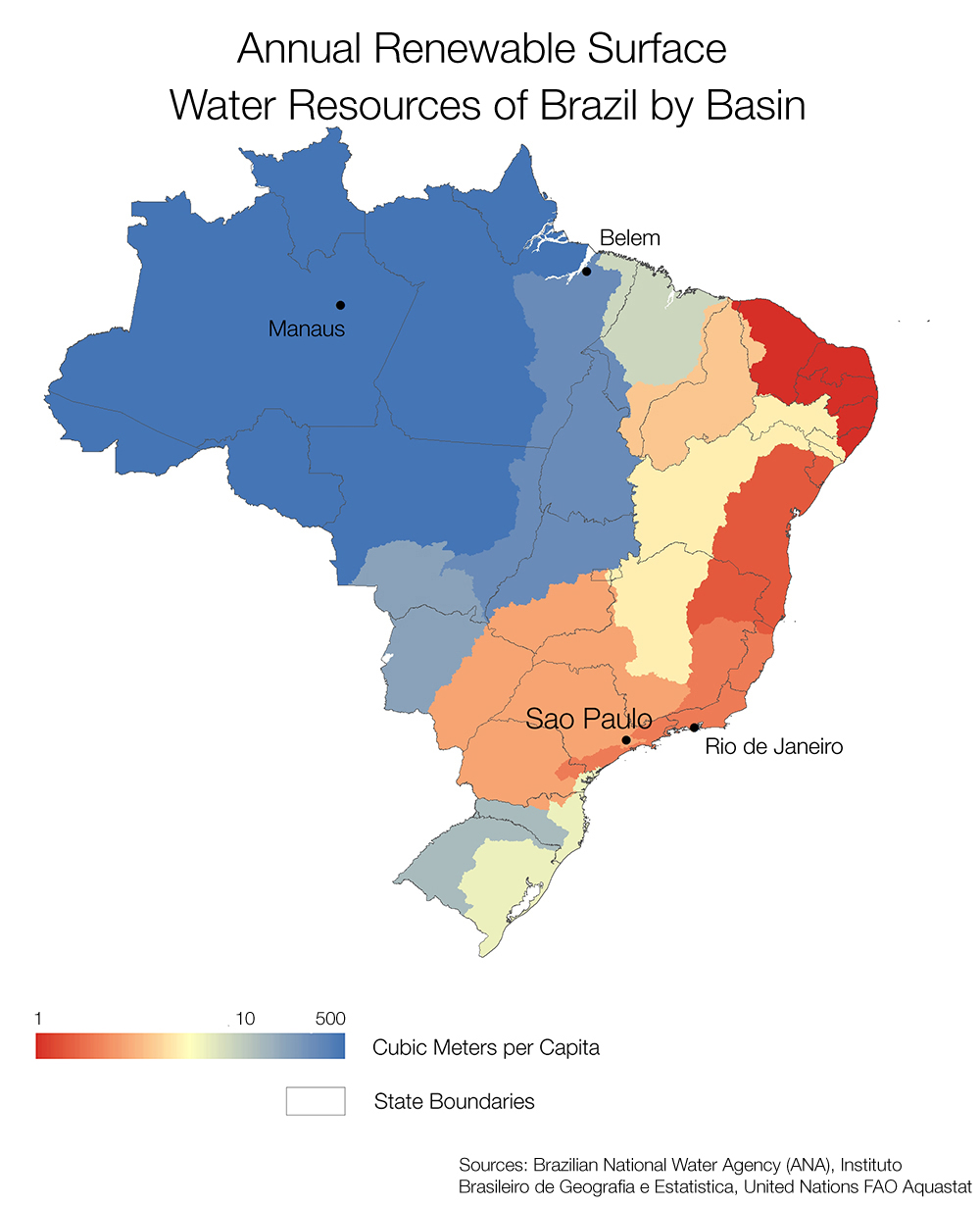

The report names Southern Africa, northeastern Brazil, eastern Australia, the Mediterranean Basin, and the Western U.S. as places where climate change will decrease the amount of freshwater. North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia face the most difficult water challenges due to demographic and economic development pressures.

Such conditions will likely not be the direct cause of violent conflicts during the next 10 years, the authors argue, because, “historically, water tensions have led to more water-sharing agreements than violent conflicts.” Still, the authors of the report state that, beyond the next 10 years, they expect water to be used increasingly as leverage between countries that share a river basin, or even used as a weapon. Further, the report notes that water delivery systems — dams, desalination plants, pipelines, and canals — are a potential target for terrorists.

Ever since the disintegration of the Soviet Union more than two decades ago, these concerns about government instability, or even collapse, have formed a significant chunk of the academic research on environmental security. The new National Intelligence Council report — and related government programs begun in the last few years — shows that leaders in the nation’s capital have grown more comfortable with the need to address non-traditional, more oblique security threats.

The report gives good news, as well, stating that there are preventative actions that can be taken, with many of the technologies available now.

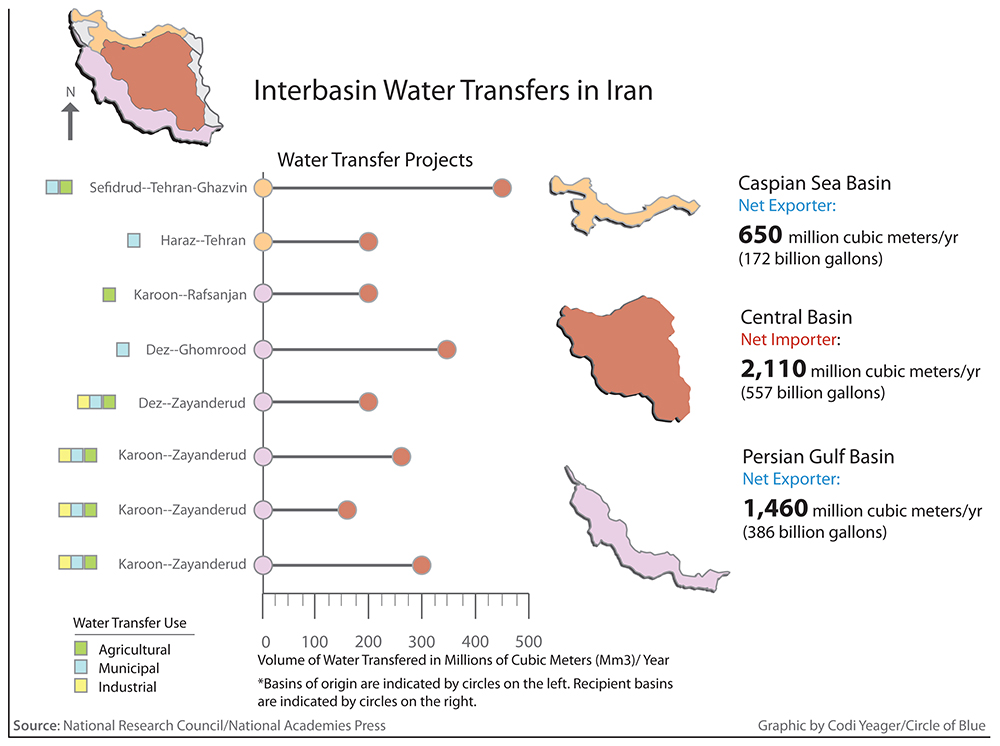

“From now through 2040, improved water management (e.g. pricing, allocations, and “virtual water” trade) and investments in water-related sectors (e.g. agriculture, power, and water treatment) will afford the best solutions for water problems,” the report says. “Because agriculture uses approximately 70 percent of the global freshwater supply, the greatest potential for relief from water scarcity will be through technology that reduces the amount of water needed for agriculture.”

A Short History of Water in U.S. Government Reports

One of the first U.S. government reports to address water in relation to national security was in 2000, with the National Intelligence Council’s “Global Trends 2015 Survey,” which sought to identify the strategic undercurrents that would shape U.S. policy.

A more rigorous assessment came five years later, with a 134-page report on water from the Center for Strategic and International Studies and Sandia National Laboratories. The “Global Water Futures report” argued that water was a blanket force: “Virtually every major U.S. foreign policy objective — promoting stability and security, reducing extremist violence, democracy building, post-conflict stabilization and reconstruction, poverty reduction, meeting the U.N. Millennium Development Goals, combating HIV/AIDS, promoting bilateral and multilateral relationships — will be contingent to some extent on how well the challenge of global water can be addressed.”

The report criticized where the U.S. government spent its foreign aid dollars for fresh water. Using data from the Government Accountability Office, it showed that aid was concentrated in war zones (Iraq and Afghanistan) and in the Middle East (Egypt, Jordan, Gaza, and the West Bank). In 2004, only 3 percent of USAID money went to countries in Africa.

Since “Global Water Futures,” however, circumstances have flipped.

Later that year, President George W. Bush signed the Paul Simon Water for the Poor Act, which made water and sanitation foreign policy priorities. As a result, the geographic distribution of water aid has changed. In fiscal year 2010, some 41 percent of the U.S. government’s water-related investments were made in sub-Saharan Africa.

Then in September 2010, President Barack Obama signed the Presidential Policy Directive on Global Development, which established programs for climate change, food security, and public health, putting these programs at the core of American foreign policy.

Funding for these programs has dropped slightly since the fiscal stimulus in 2009, but, combined, they still comprise nearly one-fifth of the State Department’s budget.

These new commitments have caught the eye of people in the water, sanitation, and health (WASH) field.

John Oldfield — the managing director of WASH Advocacy Initiative, a D.C.-based nonprofit organization, working to increase global access to safe drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene — told Circle of Blue in a December interview that, in terms of budget allocations, projects, and policies, the U.S. government is “trending in the right direction” for water and health.

Other Findings

Despite the potential pitfalls from declining water availability, the new assessment describes several ways that the U.S. could help to shape a more water-secure world. The U.S. is recognized as a global leader in water management and water technology — expertise that can be applied in a host of circumstances, from improving farming methods and irrigation efficiency to aiding water-sharing negotiations.

Technical knowledge, such as hydrological modeling and satellite data, will also be sought after, but, because agriculture uses more water than any other sector, the greatest tool to prevent shortages will be technology to reduce water needed for irrigation.

Helping countries to address these problems could bolster U.S. influence, but water stress also opens economic windows. The report notes that the U.S. is a major food exporter. As water resources become scarcer in places like the Middle East, agricultural giants such as the U.S. and Russia could benefit from higher demand for their products. This, of course, depends on global food markets remaining open, as well as prudent water management at home, where unsustainable groundwater use, poor policy decisions, and misplaced incentives are not unknown.

Reaching Policymakers and Connecting the Dots

The report makes clear that water availability will not be able to keep up with demand without more effective management of water resources, thereby hindering the ability of key countries to generate energy. Water scarcity poses a risk to global food markets and ultimately thwarts economic growth.

Such a comprehensive, networked view of water is something that high-ranking national security officials are trying to get policymakers to understand. During a Congressional hearing in January, James Clapper, the director of National Intelligence, shared the conclusions from his organization’s annual unclassified report on the most critical threats to America’s national security. The water security report released last week was prepared as part of that process.

Sitting at the witness table with six colleagues from the government’s intelligence agencies, Clapper told the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence that the security challenges today are “more complex and interdependent” than any he has seen in his 49-year career.

“Throughout the globe,” Clapper said, “wherever there are environmental stresses on water, food, and natural resources, as well as health threats, economic crises, and organized crime, we see ripple effects around the world and impacts on U.S. interests.”

Yet, many of the questions the senators asked in response — What can we do about Iran’s nuclear program? How can we shield ourselves from cyberattacks? Can you explain the machinations within Pakistan’s government? — centered on what might be called “actor-driven” events. This is the realm in which the national security dialogue traditionally and most comfortably operates: an arena where causes and effects have a one-to-one relationship and where threats can be identified and isolated.

But the seven witnesses and the threat assessment itself sought to connect these political relationships with the environmental, social, and economic substructures that can unexpectedly well up and completely change the script.

“Capabilities, technologies, know-how, communications, and environmental forces,” Clapper said, “aren’t confined by borders and can trigger transnational disruptions with astonishing speed, as we have seen.”

With this final clause, Clapper was referring to the tumultuous Arab Spring, in which popular uprisings toppled governments in Tunisia, Egypt, and Yemen. In Libya, Western air power helped rebels oust Muammar Ghaddafi. In Syria, a bloody civil war is still unfolding.

As studies begin to show a correlation between spikes in food prices and the events last year in North Africa and the Middle East, policymakers are gaining more understanding about the conditions that link national security, with water availability and climate change, said Sandra Postel, director of the Global Water Policy Project and an expert on international water issues, in an interview with Circle of Blue.

Last October, in fact, an advisory board recommended, in a report on climate change and national security, that the Defense Department include water as a “core element” of its security strategy.

Indeed, the latest national threat assessment takes the most comprehensive view of water security since the assessments began in 2006. Yet, climate change — given prominence in past reports and mentioned in the Defense Department’s most recent military operations review — was not addressed at all.

The Office of the Director of National Intelligence would not comment on why certain issues rise and fall each year. Instead, the office submitted this statement to Circle of Blue: “There are a number of important issues that the intelligence community pays close attention to, including issues related to climate change, but as the introduction [to the unclassified report] noted, ‘it is virtually impossible to rank — in terms of long-term importance — the numerous potential threats to U.S. national security.’”

Click the images below to launch slideshow.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!