Support for UN Water Treaty Accelerates

Progress on the treaty, which deals with transboundary water basins, or those shared by two or more countries, had stalled — until a major conservation group got involved.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Fifteen years ago, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a framework convention for bodies of water shared by two or more countries. The UN Watercourses Convention, as it is called, lays out a set of principles that should be addressed when negotiating international water management agreements.

After a burst of ratifications in the early days, followed by a dead period in the mid-2000s when only three countries adopted it in five years, the convention has recently seen new life.

Just this year, six countries have jumped on board: Benin, Denmark, and Luxembourg have officially approved the convention; Italy has signed everything except for the paperwork at the UN; Ireland and the United Kingdom said in June that they would ratify it.

In all, 27 countries have completed the process, leaving the convention just eight ratifications short of the 35 necessary for it to come into force. When that happens, the ratifying countries will be obligated to follow the convention’s provisions.

Legal experts told Circle of Blue that the convention is important because it sets a standard. Even now, its principles serve as a model. Two river basin agreements signed since 1997 — for the Nile River and for the Southern African Development Community, a regional group of 15 countries — have referred to and copied language from the convention.

“By itself, it won’t resolve anything,” said Joseph Dellapenna, a Villanova University law professor who has helped summarize international water law. “But it will strengthen the hand of those who are negotiating water agreements.”

Alistair Rieu-Clarke, an expert on transboundary water cooperation at the Centre for Water Law, Policy, and Science at the University of Dundee, Scotland, said that each ratification adds to the convention’s persuasive power.

“If enough countries adopt it, we can say the convention is reflective of customary international law,” Rieu-Clarke told Circle of Blue. “The opposite is also true — if it is not in force, countries can question whether it is really necessary to cooperate with core principles, such as notifying basin partners about water development projects and giving them a chance to respond.”

It Needed A Champion

That the convention is even close to 35 signatures is largely due to the work of one organization. In 2006, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), a major conservation group, decided to put its weight behind the convention.

“Most of our priority places for conservation are drained by international watercourses,” explained Flavia Loures, WWF’s point person for the watercourses initiative. “A lack of cooperation between countries over water resources was preventing us from achieving our goals.”

–Flavia Loures, program officer

World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF)

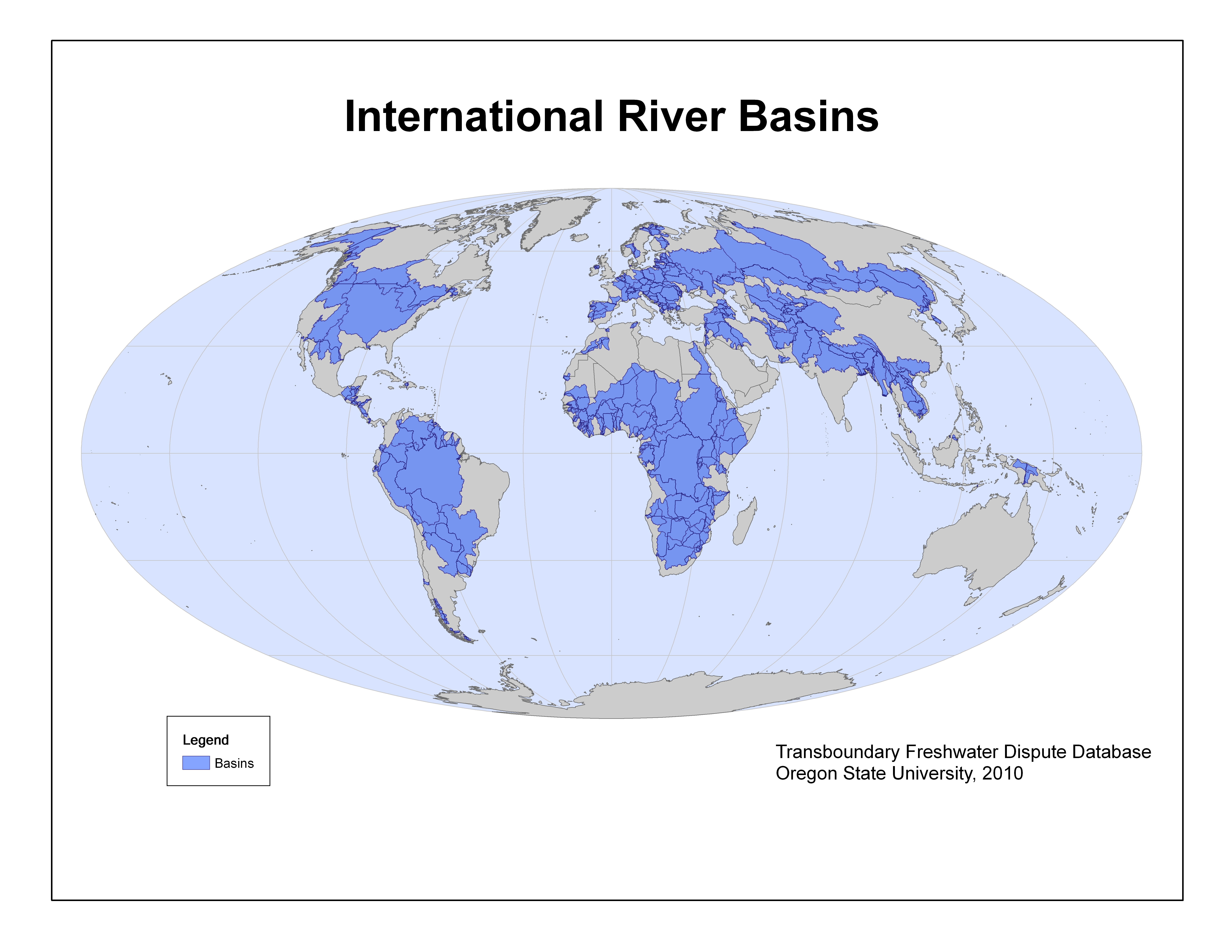

There are 276 international watercourses, or river basins, shared by two or more countries. Roughly 40 percent of the world’s people live in one of these basins.

“We looked at our on-the-ground work,” Loures told Circle of Blue, “and asked, ‘What could we add to that, to strengthen water governance?’”

The answer, it turns out, would be obvious to a political strategist.

The convention needed a lobbyist, someone to cut through the noise and bring the message directly to national governments — after all, they are the ones responsible for ratification and are sometimes oblivious to the sausage being cranked out at UN headquarters in New York.

“The convention never really had a champion for the cause back in 1997,” said Rieu-Clarke, who has helped WWF research why there was widespread support in the UN General Assembly but just a handful of ratifications.

Back then, the convention was lost in the congestion of a few frenetic years of international treaty-making, Rieu-Clarke said. The 1990s saw international treaties on climate change, desertification, and biodiversity, plus the Kyoto Protocol for greenhouse gas emissions and the Rio Declaration on principles of sustainable development.

“Maybe the watercourses convention was one convention too many,” he surmised.

In any case, Loures and Rieu-Clarke did find that many government officials were simply unaware of what the watercourses convention was or did. So WWF began holding workshops with government ministries in places like West Africa and Central America.

Ratification Process

“The convention is now in the spotlight,” Loures said. “Countries are talking about it.”

The length of the ratification process varies. Loures said that Nigeria — which marked it a priority — sped through ratification in a matter of months. In Benin, however, almost five years passed before Parliament approved the convention.

Any number of obstacles can disrupt ratification. National elections can distract government officials and internal political chaos, as was the case in Guinea-Bissau in 2010, can push a water treaty far down on the domestic to-do list.

But the convention is now on a relatively clear path. Loures said that at least five more countries–the United Kingdom, Ireland, Italy, Niger and Senegal–appear to be on track to complete the process in the next few months. That would bring the number of parties to 32. Another five countries, she said, are working a bit slower.

In a perfect world, the convetion would come into force next year, which the UN has declared the International Year of Water Cooperation. A nice bit of symmetry for a treaty long in the making.

Correction: This article originally used the Nubian Aquifer System as an example of a confined aquifer. It is not.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

A few corrections and comments related to the box entitled “Contentious and Controversial”

• The Nubian Sandstone aquifer in North Africa is NOT a confined aquifer; it is nearly entirely unconfined (while it is underlain by an impermeable base layer, it is overlain by permeable strata).

• The Nubian Sandstone aquifer does not receive an appreciable amount of water because it is located in a very arid environment. Hence, there is very little recharge.

• The General Assembly is already considering draft articles for ALL transboundary aquifers, not only “confined” or those that are disconnected from (or poorly connected to) the hydrologic cycle (s.a., the Nubian Sandstone aquifer). Those draft articles were first presented with these draft articles in 2008, but have “tabled” them twice. They are due back on the UNGA’s agenda at its sixty-eighth session in 2013. Whether they will actually consider them (or table them again) is uncertain.

• You can find the Draft Articles on Transboundary aquifers, as well as the UNGA’s 1st resolution, at http://internationalwaterlaw.org/documents/intldocs/UNGA_Resolution_on_Law_of_Transboundary_Aquifers.pdf.

• You can find a discussion of the Draft Articles and the UNGA’s 2nd resolution at: http://www.internationalwaterlaw.org/blog/2011/12/17/unga-adopts-new-resolution-on-transboundary-aquifers/

It would seem,even from the corrected infomation box, that ‘confined aquifers’ and what they mean remains unclear even to most of the engaged audience! Nothing in nature is absolute! Many aquifers have a part of their system that is confined and a part that is unconfined – there are many basic hydrogeological texts where clarification on this can be obtained. This has also been covered in great detail in the Commentaries to the UN ILC’s Draft Articles on the ‘Law on the Use of Trasboundary Aquifers’. See refs made in previous comment.

What is more interestng is that world wide mappng & inventory has been completed to show the global ditributon of transboundary aquifers; additional mapping showing (for the first time?) both river basins boundaries and aquifer systems boundaries have been published under the WHYMAP Progarmme (see http://www.whymap.org/whymap/EN/Home/whymap_node.html ). These maps are an invaluable resource for practitioners of the art of transboundary water management (its an ‘art’ and not a skill!) when they need to account for both aquifers and river basins. The WHYMAP products show clealry in which river basins the 1997 Convention applies and in which aquifer the UN ILC’s Draft Articles apply. As nature is not absolute, there are many instances (maybe every one ?), where the provisions in both the Convention and the Draft Articles will have to be applied. While pushing ahead with the ratification of the 1997 Convention is a positive step, the adoption of the Draft Articles is equally critical. Else the 99% of the global fresh water found in aquifers may well remain ‘out of sight and out of mind’ – something that the global engaged community should not do.