Weak Monsoon Raises Specter of Drought in India

Monsoon rainfall is 14 percent below average in India, which depends on rainwater to feed more than 50 percent of its agricultural land.

By Codi Kozacek,

Circle of Blue

There are more than 12,000 kilometers (7,500 miles) between the Midwest United States corn belt and the bread basket of northwestern India, but droughts afflicting these two agricultural powerhouses have serious implications for world food prices and grain stockpiles.

India’s drought — declared by the government on August 2 — is neither as severe nor as lengthy as the one shriveling U.S. crops, but the rains from the summer monsoon, known as the southwest monsoon, are 14 percent below the long-term average. The southwest monsoon rains typically supply 73 percent of India’s annual rainfall and are the primary water source for 55 percent of the non-irrigated portion of India’s agricultural lands.

–India Grain Report

USDA

The southwest monsoon stretches from June through September, but rainfall is unlikely to improve over the second half of this season. In a forecast released August 2, India’s Meteorological Department said that rainfall in August is “likely to be normal,” but that rainfall over the country as a whole could be below normal later in the season due to developing El Niño conditions that bring dry weather to Southeast Asia. Coupled with a weak and slow start to the monsoon, forecasts expect “deficient” rainfall overall.

India is no stranger to drought, and expects erratic rainfall four out of every 10 years. However, studies show that the monsoon has been getting progressively weaker over the past 50 years, while the rain that does fall comes in more extreme weather events. These trends have negative implications for India’s rice yield — the country is currently the world’s second-biggest rice producer and its third-biggest rice exporter. The worrying trends also add a concern to the global food outlook at a time when the world’s agricultural giants are being repeatedly hit by droughts and the world’s population is increasing rapidly.

India’s Drought Impacts Crop Yields

The driest region is the northwest, which had received only 80 percent of its long-term average rainfall as of August 23, according to India’s Meteorological Department. This region envelopes some of the most productive agricultural states in the country, including Punjab, which produced 27.2 million metric tons (1.3 billion bushels) of food grains in 2010-11, government statistics show. Other major producers in India’s northwestern region include Rajasthan and Haryana, as well as the more north-central Uttar Pradesh.

The rain deficits prompted the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) in July to drop production estimates for India’s rice crop by 2.5 million metric tons (121 million bushels). These numbers were further reduced by 6 million metric tons (291 million bushels) on August 3, bringing this year’s forecast to 94 million metric tons (4.5 billion bushels) — a nearly 10 percent drop from last year’s record high production.

And crop forecasts could shrink again, if monsoon rains continue to be deficient. But, so far, rains have picked up enough to ward off any further reductions.

Rice growers in the eastern portion of Uttar Pradesh, the southern-most region of Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal in the east depend almost entirely on monsoon rains to successfully transplant their seedlings, so these regions were particularly susceptible to poor monsoon rains, according to the USDA India Grain and Feed Update.

The update added that even irrigated rice fields can be hit by deficient monsoon rains “due to depletion of rechargable groundwater and surface reservoirs required for irrigation.”

The decrease in India’s production will result in world ending stocks for rice declining 1.7 million metric tons (82.4 million bushels) from the previous year, according to the July USDA World Agriculture Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE).

Lower Production = Higher Prices

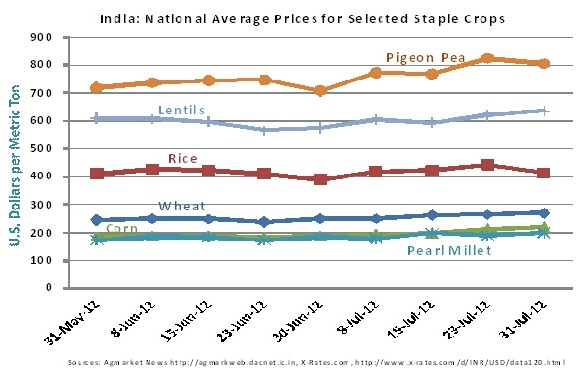

Indian food prices have responded to the drought and lowered crop forecasts, echoing the spike in corn prices occurring in the United States.

“Continued deficient monsoon rains and reports of impending drought have led to a significant increase in food prices, with prices of most food grains rising by 6 to 14 percent during July,” the USDA grain report said of Indian food prices. “The increase in the prices of corn and various pulses has been very strong, raising serious food-inflation concerns among policymakers.”

But following record crops in 2011, India has plenty of food to spare in its government-held food/grain stockpiles — 30.7 million metric tons (1.5 billion bushels) of rice and 49.8 million metric tons (1.8 billion bushels) of wheat — and the nation may use these resources to put downward pressure on prices.

India could also consider export bans on certain crops to further reign in prices, if the monsoon continues to perform poorly, but Indian rice exports are currently expected to be a full 1.8 million metric tons (87.3 million bushels) greater than in 2011, despite the reduced production forecasts.

The poor monsoon performance is expected to hit India’s economy in other ways, as well, particularly because agriculture accounted for 12.3 percent of India’s $US 1.1 trillion national GDP in 2009-10.

“We projected gross domestic product (GDP) growth of 7.3 percent on the assumption of a normal monsoon and improvement in industrial activity. Both these assumptions have not held,” the Reserve Bank of India said on July 31. “The monsoon has been deficient and uneven, so far. Also, data on industrial production for April-May suggest that industrial activity remains weak. On the basis of the above considerations, the growth projection for the current year (2012-13) has been revised downwards from 7.3 percent to 6.5 percent.”

A Growing Problem?

Even with rain deficits and some crop forecast reductions this year, India’s drought will be far from catastrophic for the agricultural sector. This is because India’s record harvests in 2011 and expansive grain stockpiles will provide a more than adequate buffer for any drop in production this year.

–Report: Climate Change, the Monsoon, and Rice Yield in India

Relatively healthy rice harvests and reserves in other parts of Asia are also providing one of the few bright spots for the global grain outlook, as other grains — corn, wheat, and soybeans — are being hit by droughts in other parts of the world.

Even so, studies have found disturbing trends in India’s annual monsoons.

“Recent research indicates that the monsoon has changed in two significant ways during the past half-century: it has weakened and the distribution of rainfall within the monsoon season has become more extreme,” wrote the authors of a 2011 report, published in the international journal Climatic Change. “The all-India mean of total June to September rainfall during 1961–98 was about 5 percent below the mean for the previous 30-year period. This reduction is more than double the overall reduction since the late 1800s, thus suggesting that the weakening of the monsoon has accelerated.”

The report says that these changes “raise concerns about food security,” as yields for kharif crops are correlated to monsoon rainfall — in other words, when monsoon rainfall declines, crop yields decline. For example, the study found that rice yields drop 0.20 percent for every 1 percent decrease in total rainfall during the monsoon months, between June and September.

Moreover, increased nighttime temperatures during the growing season were found to have an even larger impact on yields than changes in monsoon rainfall.

Probably the most interesting finding of the study, however, was that cumulative kharif rice harvests between 1966 and 2002 would have been 5.67 percent larger — a difference of 75 million metric tons (3.6 billion bushels) — in the absence of climate change.

“Climate models predict that the monsoon will continue to weaken and that the global area affected by drought will likely increase in the future, with the frequency of heavy precipitation events very likely to increase over most areas,” the report concluded. “Future impacts of these changes on rice yield in India would thus likely be larger than the historical ones estimated here.”

Blue Water, Green Water, Virtual Water

While rainwater — termed ‘green water’ — is the primary feeder of India’s agricultural land, a decline in monsoon rainfall could force more farmers to turn to ‘blue water,’ which includes surface and groundwater resources.

India already has the largest blue water footprint within its own territory at 243 billion cubic meters (64 trillion gallons) per year, which is 24 percent of the world total, according to a study published earlier this year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. A water footprint is a measure how of much fresh water a country consumes or requires for agriculture, industry, and waste disposal. Irrigation makes up the majority of India’s blue water footprint — wheat, grown in the dry rabi season, takes a 33 percent share, while rice takes up 24 percent and sugarcane accounts for 16 percent.

—The Water Footprint of Humanity

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

According to the Philippine-based International Rice Research Institute, rice farmers try to keep their fields constantly submerged in 5 to 10 centimeters (2 to 4 inches) of water, meaning that a 1-hectare (2.5-acre) rice field constantly requires 500 to 1,000 cubic meters (132,000 to 264,000 gallons) of water.

A lot of that water gets shipped out of the country in the form of manufactured goods and agricultural exports — ‘virtual water.’

Exports and imports create a global network of these ‘virtual water’ flows, where one country’s water is turned into products that are sent to another country and can have a big impact on the water resources of the producing countries. India is the third-largest gross virtual water exporter, sending out the equivalent of 125 billion cubic meters (33 trillion gallons) of water each year in exports, according to the study.

Blue water exports are especially concerning, because these water sources typically take longer to recharge.

Australia, China, India, Pakistan, Turkey, the United States, and Uzbekistan are the largest blue virtual water exporters, according to the study. Collectively, these six nations account for 49 percent of the global blue virtual water export. The study says, “All of these countries are partially under water stress, which raises the question whether the implicit or explicit choice to consume the limited national blue water resources for export products is sustainable and most efficient.”

Source: India Department of Agriculture and Cooperation; India Meteorological Department; International Rice Research Institute; Reserve Bank of India; USDA

*Note: Approximately 48.5 bushels of rice = 1 metric ton. 36.7 bushels of wheat = 1 metric ton. An average of bushel weights for corn, wheat, soybeans, sorghum, rye, barley, oats, and rice was used to calculate an approximate 47.8 bushels of food grains = 1 metric ton.

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

Looks Good.

What is under the carpet in India can be brought up.?

Gopinathan Krishnan preditced the monson last year.

Did The IMD ever gave a correct fore cast ? All talks on Mon- what basis they say it now I don’tknow.?

For your information –

Gopinathan Krishnan Forecasted “Monsoon correctly’ He commented in Hindu ” “Yes, it appears that the Pacific Ocean Warm Pool is shifting east ward. It will probably result in an ENSO event (like in 2002,2004,2006 and 2009) with a deficit rainfall over India during the summer monsoon season in 2012.

(I am a retired CSIR scientist.)

from: Gopinathan

Posted on: Apr 21, 2012 at 07:25 IST :”

(Gopinathan Krishnan’s Comment in the Hindu Newspaper, on the above report )

It was later verified to be correct.

Gopinathan Krishnan,( an Earth Scientist belonging to India, part of the “7 th world”):

P.S. No contact Pl.