Fallowing Farmland: A New Card in Arizona’s Water Shuffle

A pilot project will test how much water can be saved by not growing crops.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Arizona’s water supply system, which combines far-reaching pipeline networks with state laws written to stabilize aquifers, resembles a statewide bucket brigade — deficits in one area are covered with a splash of water from another. Now an irrigation district in Arizona’s southwest corner and a groundwater district in the state’s high-growth core are working together to add another bucket to the line.

–Patrick Morgan, manager

Yuma Mesa Irrigation and Drainage District

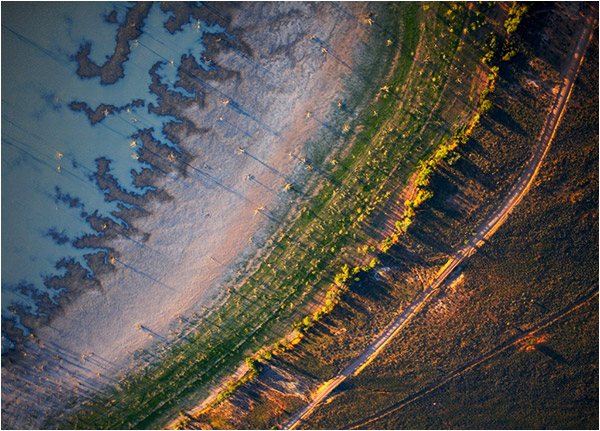

A pilot farmland-fallowing project — which will begin in January 2014 — will pay farmers not to grow crops, thus freeing up water that could be transferred to cities in the Sun Corridor, a metropolitan region centered on Phoenix, where the population could increase 50 percent by 2040 to 9 million residents, according to researchers at Arizona State University.

In a way, Arizona is copying its neighbor’s playbook. Fallowing agreements have proved popular in Southern California over the last decade. In 2004, the Palo Verde Irrigation District and the Metropolitan Water District, which represents water providers for primarily urban areas, signed a 35-year fallowing agreement.

Conservationists laud the reallocation of existing supplies, which is cheaper than converting salty water into potable supplies or building new pipelines. Farmers, meanwhile, appreciate the guaranteed paycheck.

Experiment Stage

The water, in Arizona’s case, will not go to cities, at least not yet. The agreement — signed last month between the Yuma Mesa Irrigation and Drainage District and the Central Arizona Groundwater Replenishment District (CAGRD) — is an experiment, not a full-scale operation. As the only farmland-fallowing project in Arizona, it will be rigorously monitored and measured, generating data on the amount of water the groundwater district can expect to reap if it pursues a long-term agreement, Perri Benemelis, a senior analyst for CAGRD’s water supply program, told Circle of Blue.

CAGRD is interested in diversifying its supplies. Until recently, the replenishment district exclusively used water that is delivered from the Colorado River via the 540-kilometer (336-mile) Central Arizona Project. The water acquired by CAGRD is injected into aquifers to offset unsustainable groundwater pumping. Since state law requires communities to prove that they have an “assured supply” of water, the CAGRD — by moving water around the region — makes available what nature does not.

However, Benemelis said that the district needs to acquire 30 million cubic meters (25,000 acre-feet) of long-term supply by 2015 to meet projected demands. It hopes to show a savings of 11 million cubic meters (9,000 acre-feet) from the farmland-fallowing program. In addition to the fallowing program, the CAGRD has leased water from the White Mountain Apache tribe. It is also considering recycled wastewater from cities, as well as moving groundwater from other parts of the state.

Idle Profits

Farmers, for their part, see two benefits: they will get paid and the soil quality will improve.

CAGRD is paying farmers $US 1,875 per hectare ($US 750 per acre) per year for up to three years, with an enrollment target of 607 hectares (1,500 acres). This represents roughly 10 percent of the irrigated land in Yuma Mesa Irrigation and Drainage District, which grows mostly alfalfa and citrus. Recently some 2,023 hectares (5,000 acres) of farmland in the district have been turned into tracts of suburban housing.

One criticism of fallowing programs is that they leave a patchwork of farms still in production and cut demand for local businesses that supply or benefit from the agriculture economy. According to Patrick Morgan, manager of Yuma Mesa Irrigation and Drainage District, as many as 1,200 hectares (3,000 acres) of citrus trees need to be replaced in the next few years. The fallowing phase, Morgan told Circle of Blue, will allow the soil to rest and rejuvenate while farmers still receive some income from the payments.

“This is not closing down any farms,” Morgan said.

In the end, the success of the program will be measured in two ways:

- Do the anticipated water savings materialize?

- Will farmers sign up?

The first question will be answered with a monitoring scheme that is more rigorous and at larger scale than the Bureau of Reclamation fallowing project was. The CAGRD will use both historical and actual production data for a field-by-field analysis, according to Benemelis. Answers to the second question, meanwhile, will depend on the agricultural market.

“Right now, you can make a little more farming alfalfa than fallowing,” Morgan said. “But if you run into a down market in the next few years, that could change.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!