J. Carl Ganter: The Biggest Story of Our Lifetime Is Water

For World Water Day 2013, Skoll World Forum and Circle of Blue asked four of the world’s leading water experts to weigh in. Here is what J. Carl Ganter, director of Circle of Blue, had to say about water’s connection to 21st-century journalism.

In honor of World Water Day 2013, featured below is an adapted version of J. Carl Ganter’s keynote address, given on March 19 at the Canadian Water Network annual conference in Ottawa. Ganter is co-founder and managing director of Circle of Blue, as well as vice chairman of the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on Water Security.

The biggest story of our lifetime is water. I’m a journalist and, today, the place to be is right here.

On December 7, 1972, astronauts aboard Apollo 17 took the most famous picture in history — a picture of a vulnerable little blue planet hanging in space. Twenty-five years later, Jerry Linenger launched aboard the Space Shuttle Atlantis. He was headed to the Russian Space Station, Mir, where he would spend spend five months in orbit. Plenty of time to ponder.

“Looking out the window, I would see the great sources of fresh water on the planet,” Linenger wrote to me. “Lake Baikal, deeper than deep. The Great Lakes, well-named. The mighty rivers of the world — Nile, Tigris-Euphrates, Amazon — defining civilizations, past and present. But still, when stepping back and looking at the big picture, not so much different than our little orbiting space station, a closed ecosystem. Only so many sources of life-sustaining water. And all the creatures of Earth, just like the three of us circling it, all dependent on water.”

In this closed ecosystem, we have systemic failure. A global freshwater crisis. Our blue, our water — in all forms — is in peril.

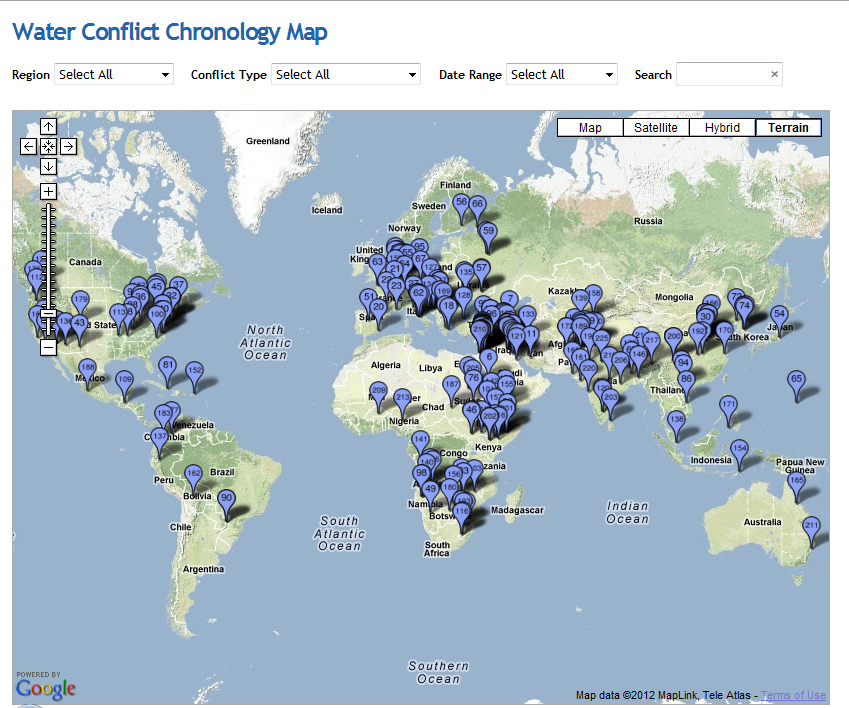

The U.S. intelligence community tells us that we should be afraid. Global instability. Drought. Disruption. Food and energy insecurity. The competition between water, food, and energy is affecting everything we care about. When there’s water scarcity, we can see the trigger: drought pushes up food prices, which causes tensions and — by many indications — violence.

At the same time, there’s the mind-numbing statistics we can’t ignore: some 800 million people on the planet are without safe drinking water; every day, dirty water kills nearly 5,000 people, mostly children; and where there is water, it’s the children who carry it.

Like this four-year-old girl in Ghana who walks six miles a day to fetch water. When these children carry the water, they don’t go to school. Their future slips away with every bucket.

And we have a sanitation disaster: nearly 2 billion people don’t have a safe place to go to the bathroom. So how do we fix this? We do it by listening better and learning from others; by knowing that there are solutions, sometimes small, sometimes globally transformative; and by understanding that there are real people living the real stories behind these huge challenges.

Let me take you on a quick tour around the world and introduce you to just a few of the people and places that Circle of Blue is finding on the front lines of a global water crisis.

In Tehuacan, Mexico, we found a city drying up. Its rainfall was decreasing. Its giant factory farms were draining the aquifers. Its farmers’ wells were dry, and its families were having to buy water for the first time they could remember. But in the dusty village of San Marcos, there was a bright spot…

Francisca Rosas Valencia told us she was planting ancient grains like amaranth that didn’t need so much water. Old crops, new thinking in the face of a changing climate. Now there’s an entire amaranth business in the villages near Tehuacan.

When we visited, we did what journalists are supposed to do: we listened. Just before we left, I asked Francisca one more question: How was the drought affecting her family? She became uncomfortable and quiet: 15 seconds, 30 seconds, a minute of silence passed. Tears welled in her eyes, and she picked up a picture of her son and held it close.

Where there was no water, there was no future. The future was leaving the village. Her son had left for Mexico City. Headed to the United States, Francisca hadn’t heard from him in more than a year; she didn’t know if he had made it across the desert to the U.S.

Through Francisca, we felt the tragic implications of drought on families, cultures, and immigration in Mexico and many other parts of the world. But we also learned there may be better things to grow where it’s getting dryer.

In Australia’s Murray-Darling Basin, we reported on The Biggest Dry, one of the world’s greatest droughts. The rice industry was collapsing, affecting food prices around the world. The situation was so stressful that some farmers were committing suicide. One radio journalist told us that she was afraid to go on the air with more bad news: another newscast could push another farmer over the edge, she feared.

Flying above Southeastern Australia in a small Cessna, I could see a small puddle of blue in the distance. After we landed, the farmer we met grumbled that he had to drill his well deeper each year so he could grow more rice in the dry lands.

We also found people like Beryl Carmichael, an Aboriginal elder. Sitting out under the stars eating stewed kangaroo, she told us how, for thousands of years, her people had survived the parched outback. She told us about Dreamtime, her connection to water, and her role in passing the spirits from one generation to the next. But gone with the desiccated rivers was her link to Dreamtime and her ancestors. Lost, she feared, forever. An ancient cultural tapestry unraveled.

Two years ago, we began working with the Wilson Center to peel back the complicated layers of China’s water and energy challenge. We found that this competition is perhaps the greatest — yet mostly unseen — threat to the country’s GDP.

During a frozen December, and while our other members of our team had fanned out across the country, I was dispatched to Inner Mongolia, home to some of China’s largest coal mines. Flying into Xilinhot, I could see a tiny farm, a speck of a house off in the distance. The lone taxi at the airport took me there, past the mines and across the frozen grasslands. That’s when I met Wu Yun. A shepherd’s daughter, she had grown up on the lush, green grasslands. But I learned that the mines are changing her life. Dramatically. Her family’s well was dry, and they had to coax an old tractor 15 kilometers to get water for the sheep and horses. The extended drought had hit hard, and the mines are draining what’s left.

It’s simple math for the world’s fastest-growing economy: in China, there just isn’t enough water to mine its coal and meet the growing power demands. It’s a simple fact of geography and supply. China is dry in the north where the coal is; the majority of the nation’s water supplies are in the south.

China is responding to its water problems in only ways a determined nation can — it’s doing everything at once.

- China is building a $US 66 billion canal and pipeline system to bring water from the south to the north.

- China is off-shoring its water footprint by investing in coal fields in Australia and food production in Africa.

- China is building dams along its major and minor rivers to reduce reliance on coal. (But in some cases, it’s building coal plants near the dams as backup. Just in case the rivers run dry.)

Can they respond fast enough? In September, we were in Urumqi, China, near the Kazakhstan border. It’s incredibly dry. Yet giant industrial bases of massive scale are under construction. They will need water for their mills, their power plants and their nearby cotton fields. But the water supply comes from shrinking glaciers, and scientists aren’t sure there will be enough water to last into the next few years.

These are decisions worth hundreds of billions of dollars. Decisions that will affect markets, food supplies, energy production, and lives around the world from a distant corner of China. Big decisions that have big consequences.

But what happens when you bring water to a community that never had it? To find out, I spent the night in Cuatro, a shanty town in the Philippine capital of Manila. At about 4 a.m., I heard something I hadn’t expected.

It was the clank and bustle of people in the streets setting up shop. They were unlocking doors, unloading fish, and washing vegetables for the morning market.

It’s not an easy life in Cuatro. There’s raw sewage that runs underfoot and few places to go to the toilet. But a recent partnership with a local water company brought fingerlings of blue plastic pipes that weave along the warren of pathways between shanties. They carry water to the community for the first time: safe water to drink and to wash with.

Residents who once spent almost half of their income buying water from private tanker trucks could now afford food, medicine, and education. They could open shops and pay the bus fare for jobs in town. And their children wouldn’t be chronically ill.

Like 11-year-old Omar. He used to work from sunrise to dusk, begging on the sweltering Manila streets. Now, Omar sells fresh mackerel at the market in the morning and goes to school in the afternoon when the fish are all sold.

But around the world, the complexities are outpacing our abilities to deal, and our future remains in doubt. We face serious enemies. They are ruthless and cold. They have short attention spans. They are not listening.

“The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.”

The water crisis is subtle, not sexy. It’s not a mainstream topic. It is slow to unfold, hard to comprehend, and — until the taps run dry and the crops wither — it’s not really relevant to the very people who have the most power to avert it.

It’s not breaking news.

The answers to the global water crisis are not a click away. They are hidden deep in warrens of urban squalor, lush grasslands, global convenings and small council meetings, remote sensors and orbiting spacecraft, and in the pages of ancient history.

The answers come from listening better, persistently tuning in to the quiet signals, the moments of epiphany.

But we’d better hurry.

From orbit, astronaut Jerry Linenger said he could watch the dust storms of Inner Mongolia blow across the steppes toward Beijing. And if we look at Los Angeles — water, drought, pollution — they don’t know political boundaries.

Remember Wu Yun? When I returned to her family’s home last September, this is what it looked like. The mines are getting closer. The sheep have less grass. And, like dotted lines on a map, the sand dunes are marching closer.

Originally published by Forbes on March 22, 2013 for World Water Day 2013. This series of articles, a partnership between Skoll World Forum and Circle of Blue, asked four of the world’s leading experts and innovators working on issues of water scarcity, security, and cooperation to weigh in to offer solutions and help better the understanding of key challenges and opportunities moving forward. This debate will also inform an upcoming session at this year’s Skoll World Forum in Oxford.

Read the other three articles in this series here:

- Michel Jarraud, chair of UN-Water and Secretary-General of the World Meteorological Organization: Water Can Be Fought Over or Shared, But Cooperation Brings More Benefits for All

- Sylvia Lee, leader of the water program at Skoll Global Threats Fund: Water as a Catalyst for Peace

- Ned Breslin, CEO of Water For People: An Inside Look at Water for People’s ‘Everyone Forever’ Initiative

Follow J. Carl Ganter on Twitter.

J. Carl Ganter is co-founder and managing director of Circle of Blue. He is a journalist and photojournalist, recipient of the Rockefeller Foundation Centennial Innovation Award, and an Explorers Club Fellow.

I represent a startup technology company with the first automated water management solution for commercial and industrial water users. We’ve won 3 major technology awards to include the Washington Clean Tech open for our innovation, No one provides real-time visibility to identify and correct waste events among the 100’s of failure points in a commercial building like we do. We’re helping a fortune 50 company achieve 22% savings over 50 locations. We’re highly dedicated to making a significant impact on unnecessarily water use on global scale. How can we engage or partner in a mutually beneficial and meaningful way, allowing us to learn and grow in our continuing effort to perpetuate sustainability in this area?