The Price of Water 2013: Up Nearly 7 Percent in Last Year in 30 Major U.S. Cities; 25 Percent Rise Since 2010

Utilities tinker with rate structures designed to stabilize revenue.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Water prices in 30 major U.S. cities again grew at a pace faster than inflation, according to Circle of Blue’s annual survey of water rates for single-family residential customers.

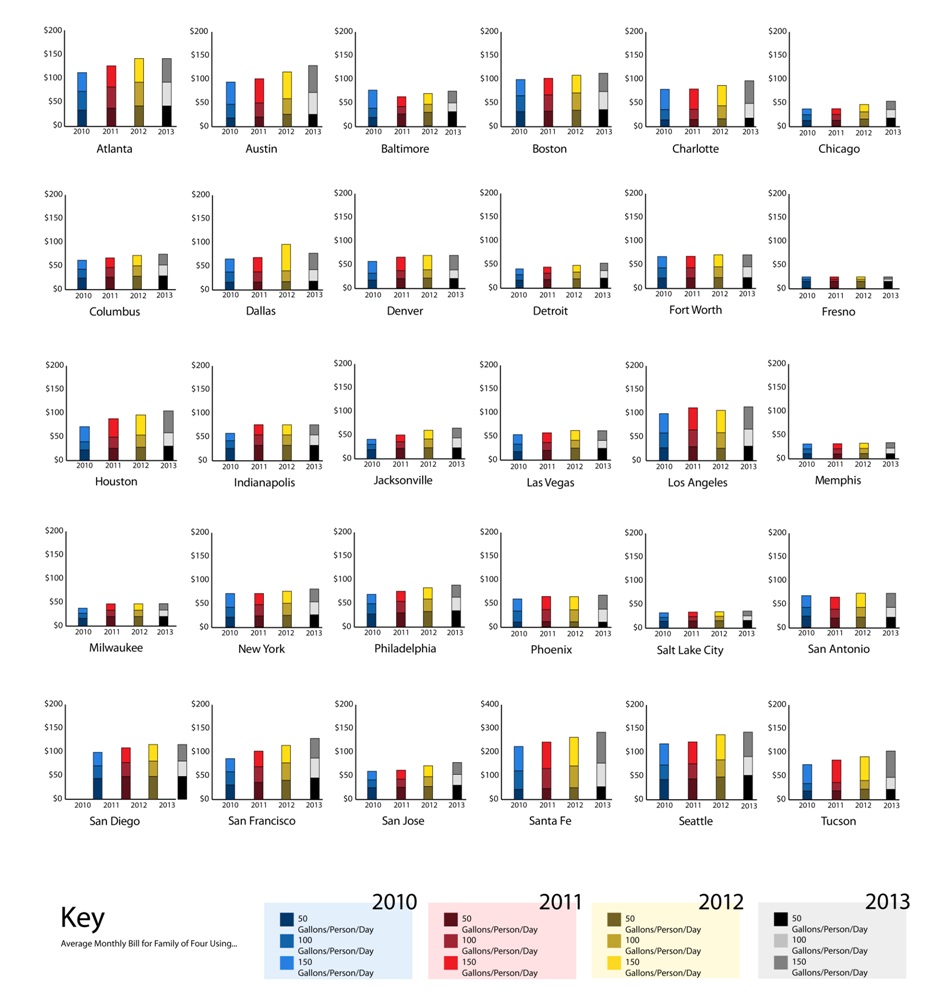

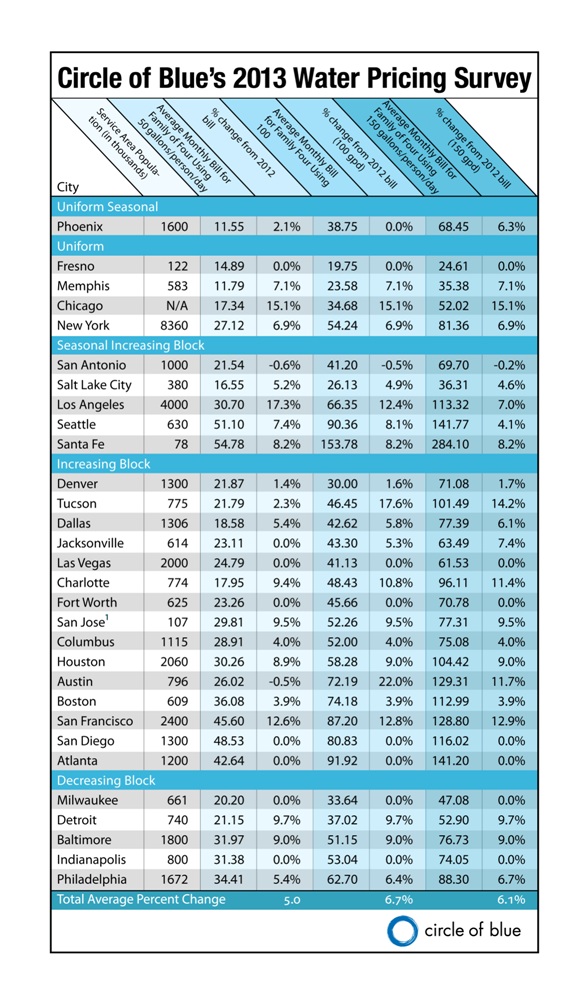

Water prices increased an average of 6.7 percent in these metropolitan areas, a slower rate than in recent years but well above the 2.1 percent increase in the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index for 2012. The median increase in water prices was 6.2 percent.

Several factors are pushing rates higher. Cities are building facilities to adapt to new water scarcities, to serve new growth, or to comply with federal mandates. With a water main break every two minutes across the U.S., an aging distribution grid sends water gushing through the streets every day. The American Water Works Association, an industry trade group, estimates that restoring existing pipes to maintain service will require as much as $US 1 trillion over the next 25 years.

These infrastructure costs coincide with stagnation in U.S. median household incomes, and even small water rate increases add up quickly. Since Circle of Blue began tracking rates in 2010, water prices have increased an average of 25 percent for the index, which covers the 20 largest U.S. cities and 10 regionally representative cities.

Because federal grants for municipal water infrastructure – mostly for sewage treatment plants to meet Clean Water Act standards – dried up in the 1980s, the burden of payment is now shouldered almost entirely by cities and their ratepayers. The U.S. Conference of Mayors estimates that local governments spent $US 111 billion on water and wastewater operations, maintenance, and capital projects in 2010, a record and almost double what they spent just a decade ago.

Yesterday, the Environmental Protection Agency said that U.S. public drinking water systems would need to spend $US 384 billion through 2030 to maintain service. Two-thirds of the price tag, which was calculated based on surveys sent to water system operators, is for replacing and repairing the vast web of water pipes that vein a city. Houston alone maintains a 11,265-kilometer (7,000-mile) network – more than enough pipe to form a double-barreled fire hose across the U.S.

“There is nowhere for us to turn for help,” Alfred Foxx, director of the Baltimore City Department of Public Works, told Circle of Blue. “Our Bureau of Water and Wastewater operates as an enterprise fund. We run the system based on revenue from our customers. When we invest in the city’s future, we do so with their money.”

From 2010 to 2011, the first year an annual comparison was possible in Circle of Blue’s survey, prices jumped an average of 8.9 percent. In 2012, prices increased 7.5 percent.

These figures are based on “medium consumption,” which is defined as a family of four using 378 liters (100 gallons) per person per day — roughly the national average for daily per capita domestic water use, as calculated by the U.S. Geological Survey.

The biggest price increases in 2013 for the medium consumption level were in Austin, Texas, and Tucson, Arizona, where prices climbed 22 percent and 17.6 percent respectively.

The two southwestern cities revamped their rate structures, which are based on the volume of water used, thus dramatically shifting how costs are distributed among its customers. As a result, people in the middle were pinched, but customers in both cities who use water sparingly saw little change in their bills. In Austin, those with “low” consumption – 190 liters (50 gallons) per person per day for a family of four – pay even less now for water than they did a year ago.

The biggest across-the-board increase came in Chicago, where Rahm Emmanuel, the Democratic mayor, has promised to speed up an overhaul of the city’s dilapidated water pipes. Following a 25 percent rise in 2012, Windy City residents were hit with a more modest 15 percent increase this year for all consumption levels.

Breaking Down Old Structures

After years in familiar circumstances, the water business is changing. Many utilities are selling less of their product.

In some ways, this is a success. Conservation messages and water-saving incentives have struck a chord, delaying the need to develop new sources of drinking water, which tend to be more expensive than earlier projects. The spread of water-efficient appliances has also dampened demand.

All this change has shaken a rather conservative industry. As utilities sell less water, the tried-and-true business model is faltering. That model was based on water sales, which account for roughly four out of every five dollars in utility revenue, on average. Most costs, however, have to be paid regardless of how much water is sold. This imbalance between fixed costs and variable revenue is where the problem lies.

Utilities can use several strategies to adapt, says Shadi Eskaf, who studies water rates at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill’s Environmental Finance Center.

They can ask for rate increases, both to cover slack demand and to pay for new infrastructure, he said.

The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) is one example. California’s largest water utility has increased its capital spending by 55 percent since 2011. The new funds will pay for a system to capture stormwater, for water main replacements, and for federally mandated reservoir covers. LADWP is also cleaning up World War Two-era pollutants in an aquifer underneath the San Fernando Valley and investing in recycled water.

On top of all that, the cost of water from the regional wholesaler has gone up.

“We’re paying double,” Kim Hughes, LADWP spokeswoman, told Circle of Blue. “We’re paying for the present and for the future. We’re building for the next 100 years.”

The New Rate Math

Occasionally, rate increases alone will not do. A rebalancing of revenues might be necessary to ensure financial stability.

“Some utilities are consciously trying to shift more of their income to fixed costs in order to guarantee revenue in the midst of declining demands,” Eskaf told Circle of Blue.

Last year, Circle of Blue found that several cities – among them Austin, Charlotte, and Las Vegas – had introduced new fixed fees.

This year, Tucson shifted some of its charges from its volume rate to a special fee it levies to pay for its share of water from the Central Arizona Project, a canal that began construction in the 1970s and reached Tucson two decades later. In addition to the fee shift, Tucson shrunk the size of its volume blocks, meaning customers encounter higher rates sooner.

Fernando Molina, Tucson Water spokesman, told Circle of Blue that the utility tried to modify its rates to reflect where the costs were going. The changes to its block structure were made to stabilize revenue and “to keep a conservation signal going,” he said.

“It’s a constant juggling action between revenue, conservation, and equity,” Molina said.

The number crunchers at Austin Water know that struggle well. After putting its new $US 4.40 monthly fixed charge in place in November 2011, Austin went back to the drawing board last year to develop a new model.

“There were concerns about how the fee affected lower-volume customers, because it was a higher percentage of their bill,” said David Anders, Austin Water’s assistant director of business and finance.

With input from an advisory committee appointed by the city council, the utility threw out the old fee and became one of the few utilities in the country to adopt a tiered system that increases as water use increases. Money from a much smaller, second surcharge will go into a reserve fund that the utility can draw on in years when revenue falls at least 10 percent short of budget forecasts.

Eskaf said that Austin’s tiered structure is similar to a model that UNC proposed two years, which allocates a customer’s monthly fixed charge according to the maximum amount of water a customer uses in any month throughout the year. Only Davis, California is considering such a rate design, he said.

“There are creative rate structures out there,” Eskaf said. “They just are not widely adopted.”

Circle of Blue gathered water rate information from the Web site of each city’s water utility or from phone calls or emails to the utilities. Prices are based on single-family residential rates and are current as of April 1, 2013. Average monthly prices for cities with seasonal rates were calculated using seasonal weighting. The fixed fees cited in the article are for 5/8 inch meters, the most common size for residential connections.

The 2010, 2011 and 2012 figures for San Antonio have been revised. Circle of Blue failed to include a few fees that the city’s water utility charges in addition to its basic rates. This revision altered the average annual increase for the entire index in 2011 and 2012 by a few tenths of a percentage point, from a 7.3 percent increase to a 7.5 percent increase in 2012, and from a 9.4 percent increase to an 8.9 percent increase in 2011. We apologize for the omission.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Thanks again for providing this information in a comprehensive form. I look forward to it every year.

Thank you for highlighting the growing cost of maintaining our aging water infrastructure. Do the values above include sewage or is it just water? Every gallon we use in our homes must return as sewage, so that cost should not be ignored.

I’m surprised Washington DC was not included on the list. The typical residential water & sewer bill in DC has increased more than 10% each year from 2009 to 2013. DC’s rate is projected to increase even more in the future in order to pay for the 20-year $2.6 billion Clean Rivers Project (the project is required by an EPA Consent Order and will reduce pollution in the Potomac River by eliminating combined sewer overflows).

Congress will soon be voting on a bill that includes a program that would provide loans to municipalities to pay for the rehabilitation, and replacement programs that are need to maintain our aging buried infrastructure. The program is called WIFIA (Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Authority) and is a part of a larger Water Resources Development Act (SB601). If it doesn’t pass, utilities will have few options for raising revenue, and families will continue to see their rates increase.

Great story Brett,

It seems like people just don’t pay enough attention to important issues like this.

Water select® works to educate people about our water info-structure and how demand is increasing too fast. You can get more info at http://www.waterselect.com

Thanks again for your good information– you are doing a great job – keep it up!