Breaking India’s Cycle of Waste and Risk

Small-scale and off-grid projects may offer solutions to India’s water, food, and energy choke points. Still, India’s government seems determined to duplicate the frantic program of industrial development, economic growth, centralization, and one-size-fits-all silver bullets that China and the West are pursuing.

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

AMBIKAPUR, Chhattisgarh, India — Though it is located just 336 kilometers (209 miles) north of Raipur, Chhattisgarh’s bustling capital, it takes either a hard drive or an overnight train ride to reach this city of spice and crowds. Further on, 40 kilometers (25 miles) down a narrow heaving road of cracking asphalt, a high ridge of rock and forest lead west to Khondla Village.

Though official India is slow to recognize it, the path to this huge nation’s successful modernization leads through villages like Khondla.

During the last two years, BAIF (Bharatiya Agro Industries Foundation) — a respected Indian non-profit that specializes in rural development and was founded in 1967 by an associate of Mahatma Gandhi — has worked with Khondla’s rice farmers to design and develop an elegant, low-cost irrigation and water-conservation project. With a goal of recharging the area’s groundwater reservoirs, which local farmers say have been declining in recent years, the project has so far led to significantly larger harvests using check dams, small ponds, shallow channels, and gravity to capture the rainfall that pours off the surrounding ridge and distribute it to the village’s rice paddies.

One significant benefit is that Khondla’s farmers earn cash wages to build and manage the project. Another benefit is that farm incomes have grown with the increased yields and larger rice harvests.

Vjiyar Singh, the 45-year-old village president and a rice farmer who has spent all his life in Khondla, summed up the project, now in its third season, this way: “I get the opportunity to work on the field and get money from the field. The crop increased, so it’s good.”

In many ways, India is a study in cognitive dissonance, a fierce and frustrating struggle between what is really working in the country — especially in India’s 600,000 villages, like Khondla — and the mega-costly and complex industrial modernization that the national government’s leaders insist is the best path for the world’s second most populous nation. In other words, more than just 1,100 kilometers (700 miles) separate Khondla and New Delhi, India’s capital.

Recharge and Replenish

Here in northern Chhattisgarh, served by narrow roads, reliable trains, trustworthy electricity, and water supplies that fit the need, Khondla’s villagers work with an expert public interest group to shape available environmental and economic resources into a sustainable water-conservation and food production pilot project. The low-maintenance and highly effective project fits its time and place. With available labor, capital, and technology, the water conserving steps taken by Khondla recharges the water table, virtually eliminates runoff and water pollution, increases harvests, and improves the financial standing of 300 farm families.

The total cost of the 110-hectare (294-acre) pilot project, which started in 2010, is 797,000 rupees ($US 159,400). This year, Khondla’s farmers are expanding the check dams, culverts, and storage ponds to cover all of the village’s 856 hectares (2,100 acres) of farmland.

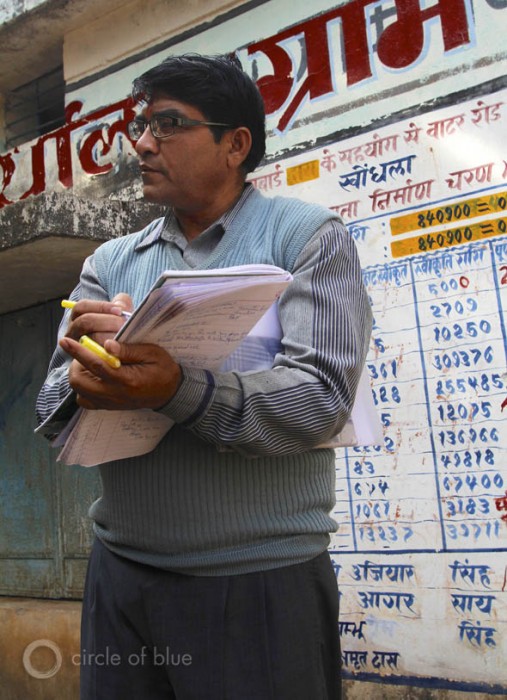

“The idea is to harvest the rainwater to irrigate and to recharge the groundwater,” said P.K. Tripathi, BAIF’s thematic program executive, who helped design the watershed development project. He points to #23 in a series of 36 small dams made from boulders, each dam numbered with yellow paint.

“The results have been very good,” Tripathi said. “The water table was at 50 meters (164 feet) deep when we started and going down more than a meter a year. Now it’s coming up.”

India’s capital, meanwhile, is a ferment of nation building and global competitive zeal. Though there is disagreement, many policymakers still look to the United States as a mature model of modern commerce. They also see China’s headstrong industrialization as a way to achieve it.

India’s 12th and newest Five-Year Plan (2012-2017) calls for expensive infrastructure projects in water supply, energy expansion, manufacturing development, and transportation — rebuilt irrigation systems, new factories, new power plants, larger coal mines, modernization of a substandard electric grid, expansion of the national rail transport network, and more urban subways. The goals are ambitious:

- Keep annual economic growth above 7 percent.

- Add tens of millions more citizens to the ranks of the middle class.

- Achieve these objectives in a way that significantly reduces the harm that India’s growth is putting on its water, land, air, and mineral resources.

Whether India can come close to meeting these objectives is very much in doubt, according to authorities in and out of government. For instance, the national economy is growing this year at an annual rate of 4.8 percent, according to government figures released in July, which is the slowest pace in a decade. Economists blame declines in services and manufacturing. But a number of the nation’s top specialists in water resources, agriculture, and energy say that the nation’s endemic inefficiency in water use and energy production, and the country’s impenetrable bureaucracy are discouraging native entrepreneurs and foreign investment.

“We have so many questions that need to be asked in a different way,” said Ashok Jaitly, a distinguished fellow and water resources specialist at The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), in an interview with Circle of Blue. “We have more people in the middle class, and their expectations are high. They want a lot more of the good life, but they aren’t willing to pay more for it. We also are a nation that is still rural, and heavily influenced by millions of small farms and 700 million people who live and depend on them.”

Jaitly acknowledged that India’s Western-style, energy-intensive, capital-consuming program of economic development has, indeed, ended the threat of food scarcity, modernized cities, and lifted 200 million Indians from poverty to the middle class. However, new data about static coal production, diminished economic performance, and rising state and federal deficits indicate that India’s development strategy is faltering while ecological havoc mounts.

Jaitly and other environmental and policy specialists outside the government are convinced that two decades of Western-style development has also produced a record of polluted water resources, dirty air, shortages of electricity, and weakened state and federal treasuries.

“We have no easy answers. We have limited financial resources,” Jaitly added. “We have limited water resources. We have limited land resources. Conflicts are emerging. It’s a question of how to distribute what we have. What we are doing now is not sustainable. It has to change.”

That is precisely what the water conservation project here in Khondla represents: a change from big to right-sized and right-priced for its context. The Khondla project indicates that India can design and build low-cost infrastructure that fits the local context, strengthens the economy, and operates in a way that improves ecological security.

Yet from a policy perspective, the project suffers from a noxious infection that spreads to most projects in India of similar sustainable goals and scale — it is considered well outside the mainstream of India’s national development strategy.

Though 85 percent of the cost of the Khondla project is supported by India’s National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development, both the bank and the project are viewed nationally as almost sideline activities — not big enough or expensive enough or complex enough to be considered mainstream. In 2012, the rural development bank’s budget was 85.82 billion rupees ($US 1.65 billion), according to the annual audit. That is one-half of 1 percent of the central government’s budget of 16.65 trillion rupee ($US 330 billion).

The Khondla project is one in a spectrum of ecologically safer — and generally lower cost — solutions that are available to break India’s chain of risk and relieve the choke points that have formed around India’s water supply, agricultural production, and energy sectors. Even though several are led by government agencies, including a bid to increase wind and solar energy production, none are considered genuinely mainstream in the same way that India has pursued building new coal-fired power plants and hydropower dams or studied the rerouting and linking of its interior rivers for irrigation.

Curtail Water and Power Subsidies

Water, agriculture, and energy policies are devoted to employing hundreds of millions of people while feeding the poorest. The result, though, has prompted over-pumping of groundwater, huge grain surpluses that are difficult to store and distribute, and vast waste of electricity.

According to government, academic, and research experts throughout India, charging a price for water will reduce overpumping, put limits on electricity consumption for irrigation, and bring needed revenue to state and private utilities that are investing in new sources of power. But farming states are reluctant to consider changes.

“Political power rests with farmers,” said Rajinder Sidhu, dean of the College of Basic Sciences and Humanities at Punjab Agricultural University. “Candidates who suggest such changes don’t have much of a chance.”

Only one Indian state, Gujarat, has tried this approach. According to India’s national Planning Commission, Gujarat spent 62 billion rupees ($US 1.25 billion) from 2003 to 2006 to separate 800,000 electric irrigation pumps from the rest of the state grid, provide farmers eight hours of power only at night, and require farmers to pay for the electricity they used. The objective was to recharge the state’s groundwater by reducing pumping and allowing rainwater to flow back into the system.

The scheme worked. The net result, said the commission, cut power use in half, stabilized groundwater levels, and improved the overall supply of electricity to residences and businesses. The number and length of power outages dropped sharply, the agency said.

“This could be a better way of delivering power subsidies that cuts energy losses and stabilizes the water table at the same time,” said the Planning Commission, in describing the Gujarat results in the latest Five-Year Plan.

Small-scale and Off-grid

Over the last decade, India has almost doubled its electrical production, according to the Ministry of Energy. In 2011, India produced 923 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity, 65 percent of which came from coal. But India’s electrical sector is at battle with itself. That same year, India lost almost 200 billion kilowatt-hours of power due to its old and inefficient electrical grid.

Described another way, of all the power India generated last year, one-fifth of that electricity never reached customers — it literally disappeared while being transported from one section of the country to another. (For comparison, U.S. electricity transmission losses are around 7 percent, according to the Energy Information Administration.) Not only is that power wasted; so are the billions of cubic meters of water that it takes to produce that power. Additionally, hundreds of millions of tons of carbon emissions are needlessly created in the process.

Instead of pursuing a mammoth and expensive program of Western-style centralized electrification — which includes constructing high tension lines across mountains and forests, as well as adding 20,000 megawatts of new coal-fired generating capacity to the grid annually — small energy projects seem precisely what India could use, since more than 400 million Indians, or one-third of the country, still live without electricity, according to the central government.

India’s national Planning Commission suggested in the latest Five-Year Plan that an alternative approach is to pursue a decentralized power grid, village by village, by hooking homes up to solar-powered local installations. The government has proposed building 2,000 megawatts of off-grid, decentralized solar power in rural areas by 2022. One big step toward that goal is a 30 percent capital subsidy on the installation and equipment costs that is provided to developers.

The small solar program is part of a larger government-sanctioned and -financed program to encourage electricity production with clean alternatives. In 2010, as part of its formal National Solar Mission, India set out to develop 22,000 megawatts of generating capacity from solar energy — half from photovoltaic panels and half from concentrated solar plants that use reflective panels to focus the sun’s energy on a boiler to produce electricity.

The solar project, though, is largely stalled, said the authors of the latest Five-Year Plan.

“The concept of microgrid, even though attractive, has so far not been effective in augmenting rural power generation,” they wrote. “This is mainly because the developers have found it difficult to get reasonable returns on their investments and they are unable to collect adequate revenues to cover operating expenses, despite the initial capital subsidy.”

When matched up against the investments in developing coal and other fossil fuels, the clean energy program is a comparative trifle. From March 2012 to March 2013, India installed 754 megawatts of solar-powered electricity, bringing the national total to 1,686 megawatts of generating capacity attributed to solar. In the same year, India installed 1,699 megawatts of wind energy generation, bringing total wind generating capacity to just over 19,000 megawatts, according to India’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy. In contrast, from 2010 to 2013, India put more than 60,000 megawatts of generating capacity online that was fueled by coal and natural gas.

Byproducts, Biogas, and Biofuels

India is concerned about its rising climate-changing emissions and the role that carbon is playing to disrupt the country’s rain and snowfall, both of which are decreasing across India, according to government reports. Though India wants to reduce carbon emissions and diversify its electrical generating fuel sources, according to its Planning and Energy ministries, the nation’s interest in biomass and biogas is not keen.

In 2010, India met a four-year goal of adding 457 megawatts of biomass- and biogas-produced electricity, according to a United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) report. But generating capacity from plant-based fuel is still only 3,700 megawatts, or 1.5 percent of India’s 240,000-megawatt generating capacity. In terms of installed electricity-generating capacity, it ranks fifth behind coal, crude oil, natural gas, and wind, according to the Renew India Campaign.

On 32-year-old Mandeep Sekhon’s eight-hectare (20-acre) farm in northern Punjab state, the gas for the kitchen stove comes from the manure of eight water buffalos that the family keeps for milk. Started by his grandfather during the 1970s, Sekhon says the off-grid biogas system provides more than his 8-person household needs.

“It never turns off, like the electricity does sometimes, and it’s a free resource,” Sekhon said. “It just makes sense, and it’s easy. Why wouldn’t we do it?”

The biogas and the compost are useable components of what would otherwise be an idle waste product of Sekhon’s farm. But harvested and used on a small-scale level, the system increases both the farm’s efficiency and yield, in addition to lessening the need for external inputs like natural gas and fertilizer.

Similarly, India’s rice-processing sector in Punjab and Haryana burn leftover rice hulls to produce the heat that dries the new grains that are put through the system. Likewise, in Chhattisgarh — India’s largest iron and steel manufacturing state — manufacturers offset some of their coal usage by burning rice hulls to heat the boilers that provide electricity to the steel-making furnaces..

In Tilda, a farm community in Chhattisgarh, 34-year-old entrepreneur Gaurav Jindal is working with his brother and several other closely related investors to develop a cleaner-burning alternative to coal-fired power. He is developing an experimental program of biomass cultivation on his 60-hectare (150-acre) Raipur Agro Farm, where a hired hand cultivates a half-hectare (one-acre) pilot plot of Napier grass, a fast-growing perennial that is native to the African grasslands.

Jindal is just as busy cultivating new investors — as well as developing harvesting, drying, and processing techniques — to see if the experiment can be scaled up and turned into a new cash-generating energy supply. Raipur Agro Farm’s first crop, planted in November 2012, was ankle high during a visit in December. Reaching nearly four meters (12 feet) in height after only a few months, Napier grass can be harvested three or four times a year. Since up to six hectares (15 acres) of new growth can be produced from the seedlings of just a half-hectare (1-acre) plot, Jindal told Circle of Blue, Raipur Agro Farm could be full of Napier grass by the end of this year.

“We wanted to work on something different that could make a difference,” said Jindal, who has degrees in physical therapy and law. He moved his family to Tilda to start the biofuel-farming venture. “There’s a huge requirement for biomass in our steel plants. There aren’t enough rice hulls.”

Jindal said he also is driven by a sense that government cannot be responsible for making all the changes. India’s entrepreneurs and young professionals must make a bigger difference than they are now. There is a sense of unease, he said, about India’s goals, its national agenda, and its prospects.

Very clearly, Jindal is tapping into a developing mood of uncertainty, even worry, in India.

Big Threats To India’s National Security

In May, the Lowy Institute for International Policy and the Australia India Institute picked up the same trend. The two Australian think tanks published a nationally representative survey of how 1,233 Indian adults viewed their country’s progress. The survey found that while 74 percent of those responding to the poll were optimistic about the economy, Indians were divided about the consequences of high-speed mega project growth; 45 percent said they either did not benefit economically or were worse off than they were.

Indians who responded said that they worried about possible wars with Pakistan and China, as well as home-grown terrorism. But the issues that really attracted their attention and generated lingering fears, according to the survey, were how poorly India is managing its natural resources.

“Shortages of energy, water, and food, along with climate change,” said the survey, “were viewed as the country’s most important challenges, with 80 percent to 85 percent of Indians rating these issues as ‘big threats’ to their country’s security.”

India’s leadership, well aware of these risks and how the nation views them, is nevertheless pursuing a development strategy that could be defined as an anti-strategy. The country is careening into the water-scarce, climate-altered, fossil fuel-challenged 21st century. But its schemes for producing energy, using water, and building a durable economy much more readily fit the growth-at-any-cost, care-little-about-resource constraints of the 20th. Khondla Village’s project to conserve water represents much more than an ingenious means to save energy and produce ample harvests. The tiny settlement, set at the base of a rocky ridge far from the mainstream, heralds a fresh reckoning in India with the real economic opportunities and environmental stability that comes with truly understanding the limits of this time and this place.

Map by Jinah Park, undergraduate student at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism. Photos by Aubrey Ann Parker, Circle of Blue’s news editor. Reach them at circleofblue.org/contact and circleofblue.org/contact.

Choke Point: India is produced in collaboration with the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and its China Environment Forum, with support from Skoll Global Threats Fund. The Wilson Center’s Asia Program, which provided research and technical assistance, produces substantial work on natural resource issues in India, including articles and commentaries on energy, water, and the links between natural resource constraints and stability.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider