Colorado River Research Group Delivers Message of Water Limits

Veteran scholars argue that creative solutions for the iconic watershed must begin with a hard fact, something our Brett Walton finds refreshing.

I have been reporting on Western water issues – specifically the Colorado River Basin – since 2009. Over the past five years, the question of how to meet current and future water needs in the iconic watershed has taken on new urgency as a long drought and steady water consumption sap both reservoirs and aquifers. Typically the debate is one of bridging the gap between expected demand and a shortfall in supply.

But a refreshingly direct statement was released this week from a new university research group that is dedicated to Colorado River issues. In the second paragraph of the group’s first policy paper, the message about limits hits with force and clarity:

“Water users consume too much water from the river and, moving forward, must strive to use less, not more. Any conversation about the river that does not explicitly acknowledge this reality is not helpful in shaping sound public policy.”

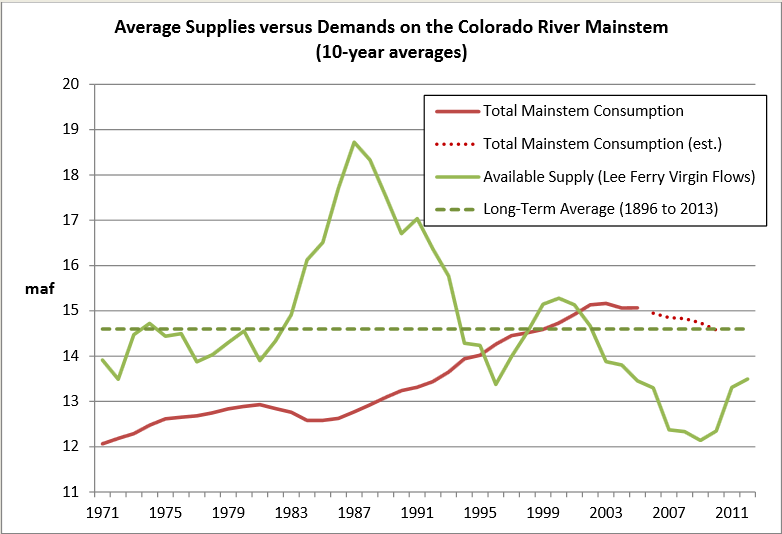

Such sentiments are a sharp turn from a history of increasing consumption, a pattern that no longer seems tenable. As the researchers point out with graphs of shrinking water supply and rising demand, the river’s ability to drive more growth in the future cannot be hitched to the same tactics that led to economic prosperity in the 20th century. Those tactics depleted the river to the point that it no longer touches the sea. (Note: The Colorado River did reach the ocean this spring as part of an experiment to restore the river’s delta. The flush of water was part of a November 2012 agreement between Mexico and the United States.)

“It’s such a simple message,” Doug Kenney, director of the Colorado River Research Group, told me, referring to the principle of using less. “It’s not like we’re getting veteran researchers together and coming up with something completely new. It’s an obvious problem and an obvious solution. We just need people to say it.”

From Constraints Come Creative Solutions

The research group is a pet project that Kenney, the director of the Western Water Policy Program at the University of Colorado, Boulder, has been pondering for two years.

A grant from the Walton Family Foundation – no relation to me – gave life to the vision, and this fall Kenney began handpicking his research dream team. Each of the 10 members that he selected is a respected scholar with decades of experience studying the Colorado River. Their expertise strikes at all angles – public policy, law, hydrology, water management.

Kenney’s inspiration came from another arid river basin, Australia’s Murray-Darling, a watershed that crashed during the horrendous Millennium Drought of the first decade of this century. In those bleak years, the Wentworth Group, a collection of scientists – “esteemed people with clout,” as Kenney put it – came together to guide political leaders through the crisis.

“It looked like they helped steer the conversation in a productive way,” Kenney explained.

For Kenney’s group, the conversation begins with the idea of limits. Going by the long-term historical record (1896-2013), water use in the Colorado River Basin began outstripping the average supply in the late 1990s or early 2000s. The Basin has since endured the driest 14-year period on record by depleting its two huge reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell. With both lakes less than half full and with the knowledge that river flows will likely decrease even more as the planet warms, a continuation of past water-development policies seems absurd.

Yet the group’s goal of redirecting water policy in the Southwest will be a formidable challenge.

Obstacles

Earlier this year, I spoke with officials in each of the four Upper Basin states: Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. According to legal tradition, the Basin is divided in two, and each half is granted by treaty the use of 7.5 million acre-feet of water from the river.

- The Lower Basin – the states of Arizona, California, and Nevada – is already using its full allocation.

- The Upper Basin – Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming – is using roughly 60 percent of its share, but all four states are planning to pull more water from the river, to use for irrigation or urban growth, energy development or water rights settlements with Indian tribes.

“We have mapped out how the remainder of our allocation can be used,” Eric Millis, director of the Utah Division of Water Resources, told me in June. “It’s going to happen sooner rather than later. We have a place for every drop.”

All of the water officials that I have interviewed recently about this issue told me that they were thinking about the risks involved but that the existence of risk alone would not cause them to shy away from a project.

As more water is used, the potential for a shortage increases, but each state will determine its own acceptable level of risk. It is this lack of Basin-wide perspective that Kenney says is missing in these debates about new withdrawals. Each project is analyzed individually, but the accumulation of such diversions will – drop by drop – magnify the risks for everyone.

If not more diversions, where does new water come from? Kenney is careful to point out that the principle of less use does not mean a grounding of the region’s economy. Embracing a less-is-more frugality has a way of generating creative responses to increase efficiency and wring out the waste from the system – an idea that any college student on a budget would understand.

To that end, Kenney said his group will be publishing short policy briefs every couple of months that will address the benefits of these water-saving adaptations – measures such as transfers of water between farms and cities, fallowing farmland, and irrigating with less water. Beyond the policy briefs, Kenney is not sure where the group’s path leads.

“We’re still evolving,” he said.

I will be following Kenney and his group in the coming months. What other groups are doing interesting work on the Colorado River? Contact Brett Walton, or via Twitter at @waltonwater, or use the comment form below.

— Brett Walton, reporter

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

The graphic should be up to date, and show data at least up to year end 2013. The impression given is that the numbers require some delayed tallying. As you know, the reality is that consumption is measured in real-time, and the data publicly disseminated on a daily, weekly and monthly basis on numerous government and user group websites.

Recently, a published study showed that California’s drought was the worst three year drought in 1200 years.

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/12/141205124357.htm

The fact that life in the Desert South Western US even goes on, without experiencing a collapsing economy, or a mass exodus of the population, is testament that cooperation, planning, and management of this limited resource, is working. As always, thank you for your insightful reporting on these water issues.