California Drought Helps Rim Fire Recovery

Little rain is not a problem for land managers working in the aftermath of one of California’s largest fires.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

For the land and water managers working in the aftermath of one of the largest fires in California’s history, the lack of rain and snow – and more significantly the absence of land-ripping thunderstorms – has been a spot of relief in an otherwise bleak and trying year.

Blackened trees and charred homes are misery enough after a destructive blaze. But a severe forest fire also prepares the land for a destructive second act: a flood of muck and debris into streams and reservoirs after a heavy rain. In recent decades large forest fires in the American West, from California to Colorado, have cost water utilities millions of dollars in clean up costs.

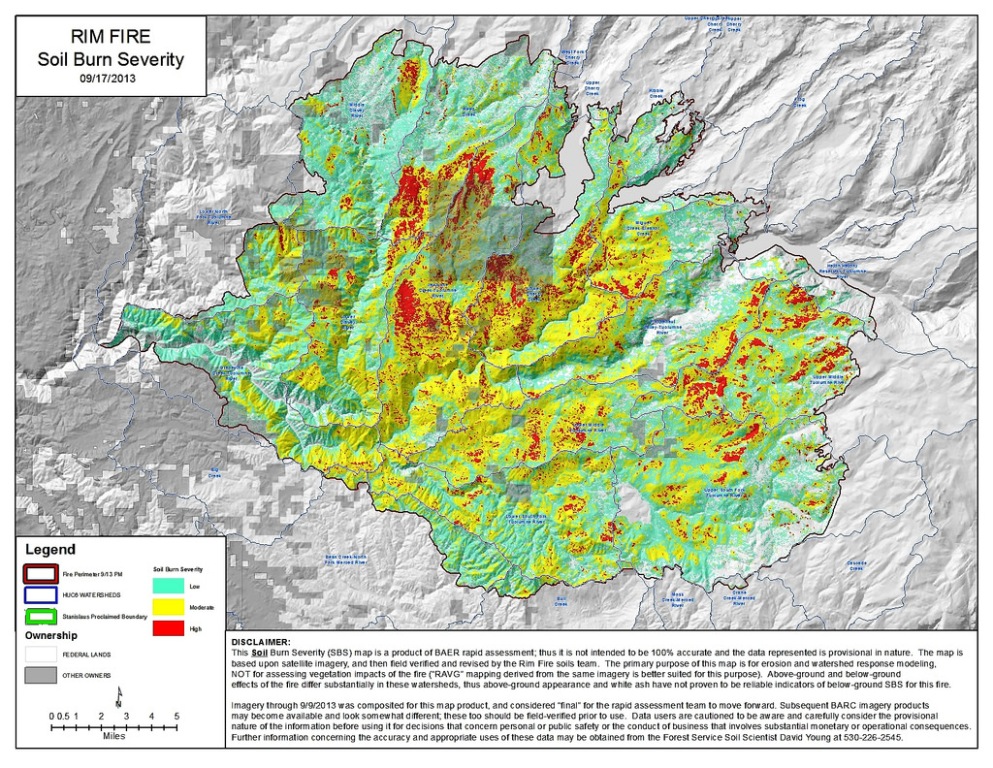

The Rim fire burned more than one quarter of a million acres last August in Stanislaus National Forest and Yosemite National Park and cost $US 127 million to snuff out. A federal grand jury indicted a hunter last week for accidentally starting the inferno.

Yet the curtain has not lifted on a big second-act flush in the watershed. For that, California’s record drought – which has prompted unprecedented reductions in water availability – is a silver lining.

“The drought has been somewhat beneficial to the watershed,” Mary Moore, a U.S. Forest Service hydrologist working on the Rim fire recovery project, told Circle of Blue. “The rain has been light, wetting rain. That has allowed the seed bank to reestablish.”

The seed bank is the stock of grasses and young trees that begin to push through the denuded soil.

“We’re starting to see green up in the burned area,” Moore said. “There haven’t been any significant effects in degrading the watershed – no gullies or rills.”

Utilities operating in the watershed downstream of the fire are relieved too. No overwhelming cascade of dead trees, brush, and sediment has washed into Don Pedro reservoir, a large manmade lake on the Tuolumne River, said Calvin Curtain, spokesman for Turlock Irrigation District, which operates the dam and reservoir.

“Our biggest concern in relation to the Rim Fire is debris runoff into the reservoir,” Curtain told Circle of Blue. “Fortunately, in this case, we haven’t seen much runoff.”

The district has spent about $US 100,000 to guard mechanical structures in the reservoir from debris, Curtain said.

A Fear of Water

Floods are a problem after a fire for several reasons. First, dead trees and ash can turn streams into a thick cauldron of goo. Fort Collins, Colorado, for instance, sealed its water intake from the Cache la Poudre River in July 2012 after a rainstorm over the recently extinguished High Park fire caused a spike in particulates and a rapid degradation of the watershed.

The second problem occurs if the fire burns with such intensity that it creates a hydrophobic layer of soil that repels water like Teflon.

In the Rim fire, some 7 percent of the burn zone was classified as “high severity.” But roughly 40 percent of the burned acres show hydrophobic soil properties, Moore said.

A week ago Moore was in the field assessing the soil. She found the water-repelling layer at a depth of 2.5 centimeters (1 inch). All of the soil above the hydrophobic coat could potentially wash off.

“One inch is not as scary as three or four,” Moore explained.

Evidence of the flood risk came in late July when one of the few large storms to hit the area parked over Granite Creek. Almost 5 centimeters (2 inches) of rain fell in an hour. Moore said the storm tide overwhelmed a culvert large enough for a grown man to walk through.

Hitting the Utility’s Wallet

Turlock Irrigation District has spent only $US 100,000 responding to the Rim fire. Not every utility gets off so cheaply.

Fires in 1996 and 2002 clogged Strontia Springs reservoir and led Denver Water, the owner, to spend $US 26 million to dredge the facility and reseed the surrounding forest.

In Southern California, a series of storms in 2010 that followed a destructive fire in Angeles National Forest prompted a similar response from Los Angeles County, which spent $US 30 million to clear debris from basins it uses for flood control.

After these experiences, several utilities are taking preemptive action. Denver and Santa Fe are among a growing number of cities that are adding the costs of forest restoration and fire prevention to their water rates. They seek to reduce the risk of a catastrophic fire in the watersheds from which they drink.

The U.S. Forest Service, because it often oversees the land upstream of the reservoirs, usually facilitates the programs and has agreements with Colorado Springs in addition to Denver and Santa Fe.

The Bureau of Reclamation, a large federal water agency, joined the party last June as part of the Western Watershed Enhancement Partnerships, one of President Obama’s many climate change initiatives. River basins in six states – Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, and Washington – were selected for the program.

These efforts will take time – both to thin forests before a fire and guard against ill effects afterward.

Moore, the U.S. Forest Service hydrologist, said that a watershed takes as many as 10 years to recover from a serious fire. Significant damage to rivers and streams can occur even five or six years after the smoke has cleared.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

The unidentified Forest service employee is Alex Janicki, forest soil scientist on the Stanislaus National Forest.