Colorado River’s Course Through A Drying Landscape Is Draining Lake Mead

Along the 1,800-mile river basin, locals wrestle with water demands.

By Heather Rousseau

Circle of Blue

The effects of lingering drought, and the unrelenting demand for water from farmers, cities, and energy producers converged today at Lake Mead, which drained to its lowest level since 1937 when the Hoover Dam closed off the Colorado River to begin filling the largest reservoir in the United States.

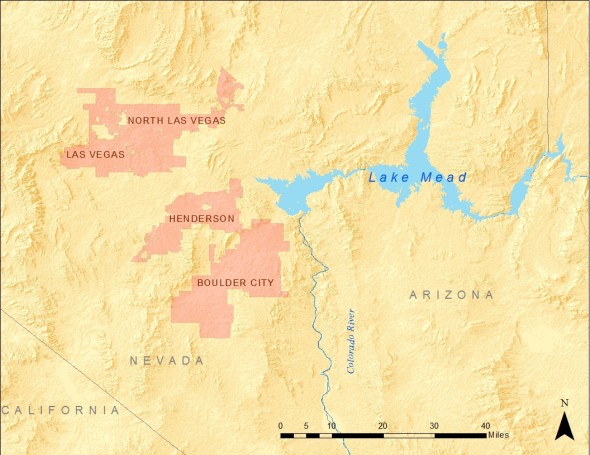

In dropping to a record-low water level the huge lake, which straddles the border between southern Nevada and northwestern Arizona, has emerged as an important measure of water insecurity in the American West. Just as gasoline prices serve as a national gauge of American economic stress — relieving psychic pressure as prices go down, causing strain as they rise — Lake Mead’s steadily declining water levels are a visible and widely reported gauge of intensifying water scarcity in the fastest growing region of the United States.

Lake Mead sits near the end of the Colorado River, which stretches 2,900 kilometers (1,800 miles) across seven U.S. states before entering Mexico. Its course is through one of the earth’s grandest landscapes. Lake Mead reflects the mammoth scale of the geography and its drying condition.

The lake, 193 kilometers (120 miles) long, supplies water to 40 million people in two countries. The federal Bureau of Reclamation announced last summer that there will be a record low release of water this year from Mead’s sister reservoir Lake Powell, a move that could prompt limits by 2016 on water deliveries to two states in the Colorado River’s Lower Basin. Last year, American Rivers, an advocacy group, placed the Colorado at the top of its annual list of the nation’s most endangered rivers, citing threats like dam projects, warmer weather, municipal water diversions, and changes to the river’s flow. And though heavily regulated by dams and canals, the Colorado River can scarcely meet current water demands, let alone the future pressures from population growth and climate change, according to a Reclamation study, released in December 2012.

Today, Lake Mead is over 60 percent empty. The last time the lake was full was in 1983.

In the rural farm counties and growing cities in the Colorado Basin, and especially in and around Las Vegas, which draws its drinking water from Lake Mead, the civic discomfort over Lake Mead’s declining water levels is steadily evolving into alarm. Ranchers and kayakers, farmers and energy developers, families and government leaders seek solutions amid a mass of conflicting interests, concerns about costs, accuracy of forecasts, and other issues that are not easily resolved.

Farming During Drought for an Increasing Food Demand

Just before the turn of the century, Bill O’Leary enjoyed boating trips to Baja California, where the Colorado River once flowed into the Sea of Cortez. But drought, population growth, and energy demands on the river have rendered it dry a few miles shy of the Gulf of California. Except for an experimental release this spring, not a drop of water from the Colorado River has reached the sea since 1998, leaving little fresh water for the delta ecosystem at the river’s mouth.

“This is the lowest I have ever seen the river,” said O’Leary, formerly a biology teacher from Michigan who has been farming in the Basin for 40 years. Having moved to northwest Colorado in the mid 1970s, O’Leary now sells potatoes and lettuce at the farmers’ markets in Carbondale, Glenwood Springs, and Parachute, towns that are within a two-hour drive from his fields in Grand Junction.

Last summer, O’Leary decided to try a farming tactic that uses less water, because he believes that the standard system of irrigating with sprinklers is inefficient and wasteful.

“With sprinkler systems, the water just evaporates into the air. I’m going to run the water through a pipe and put holes in it, so the water runs to the produce,” he said. “Water is the most precious resource we have. You can’t survive without it, and we certainly cannot waste it as the population grows in the Western states.”

From the headwater state of Colorado — growing corn, hay, wheat, vegetables, and fruit — to the Imperial Valley of California — supporting grazing livestock, alfalfa, carrots, lettuce, wheat, cantaloupes, onions, asparagus, orchard crops, and vineyards — a variety of food is grown in some of the driest Western states because of access to supplies from the river, as noted by Colorado River Water Users Association.

Until her retirement this past winter, Joan Mayer was an education specialist with Glen Canyon National Recreation who often spoke with large groups of students about water and energy conservation along the Upper Colorado River. During an educational talk at Glen Canyon Dam in October 2012, Mayer explained that much of the crops that are grown in the United States come from the Colorado River, which irrigates close to 2.2 million hectares (5.5 million acres) of land, according to the Bureau of Reclamation’s Colorado River Basin Supply and Demand study.

“You have the Colorado River coursing through your veins,” she said to a group of Colorado college students, making the connection from the river in front of them to the food they had eaten earlier that morning.

Drilling for Natural Gas in a Challenging Geology

“You want desert, you got desert. You want mountains, you go to the mountains,” said Brad Kesler, a local independent water truck driver who has lived in Rifle, Colorado, for 20 years and loves the area. Kesler’s full-time job involves filling his truck at Last Chance Irrigation Ditch along the Colorado River, off of Interstate 70 between Rifle and Battlement Mesa. He will use 15 cubic meters (4,000 gallons) of water in one day to keep the dust down on stretches of dirt roads that lead to natural gas-extraction areas.

Meanwhile, other traffic on the dusty stretch includes a school bus full of concerned citizens who are taking a tour of gas-drilling sites in Battlement Mesa and nearby Parachute Creek, two small western Colorado communities that are smack in the middle of an area with a deep history of energy extraction. Peering out the window, 60-year-old Lori Syme of Montrose — a small city with just over 40,000 people located about 160 kilometers (100 miles) to the south through the mountains — watches as the bus rolls past several natural gas wells in Battlement Mesa.

“There’s another over here. Wow, look at that rig,” she said to others on the tour of Garfield County. The tour was led by Western Colorado Congress (WCC), an organization of citizens who work on social, environmental, and sustainability issues. Garfield County is one of the top natural gas-producing counties in Colorado and has been featured in numerous documentary films, including the award-winning Gasland, which examined the repercussions and dangers of a production technique called hydraulic fracturing.

Fracking, as it is commonly called, is combined with horizontal drilling and has opened shale gas reserves across the country. Thousands of wells are currently being fracked in Colorado alone. The process, which uses millions of gallons of water per well, has been highly criticized due to much concern over polluted water tables.

Still, locals in the area are divided on the issue of drilling for natural gas. While organizations such as WCC are working for stricter regulations on oil and gas companies, there are many like Brad Kesler who depend on the gas industry for their livelihoods and see the situation differently.

“Without water, the gardens don’t grow. And without water, the U.S. don’t grow,” said Darrel Harrington, a Grand Junction-area water truck driver, while filling up his canister with drinking water at the local gas station before his shift to combat the dusty roads that lead to a a fracking site. “We need gas just like we need water: to get around. Water helps you walk around, and gas helps you drive around. We all want to live in a natural world, but it is basically impossible.”

Ranchers Split on Fracking

“I think it is important for her to grow up on her own family’s ranch, because it will give her a place to roam,” said Roy Savage about his four-year-old daughter, Abigail, as he holds her hand and walks past his home. The house overlooks an expansive land full of cows, an irrigated drinking pond for the cows, and an assortment of natural gas wells. Savage takes Abigail to see his friends, avid hunters, who are gutting a deer that they shot. It had been grazing near the gas pads on Savage’s land.

“Being a part of a piece of land, big or small, I think, gives a person a wider horizon. Lots of details to work out. It keeps one in touch with the neighbors and makes travel more interesting. It gives one perspective,” Savage said. Shifting to when he was growing up in the ‘50s and ‘60s, he continues, “The real problem here was that there were not enough people; there were no jobs. What happens when your kids grow up, what are they going to do? They can’t all be cattle ranchers.”

Savage understands the push and pull between water users in the Colorado River Basin all too well. A rancher turned energy entrepreneur, Savage flipped his business model upside down because of the dry years.

“I saw the drought coming, so I sold all my cows,” said Savage, whose family has a 60-year history of raising cattle in Parachute, another western Colorado community. “You can’t make ends meet with cows, and oil and gas is the only thing that provides enough revenue so you can keep the ranchers.”

In addition to leasing the mineral rights for what lies below the surface, Savage also rents his land to other ranchers to graze their cattle.

“Water and energy are inextricably linked,” Savage explained. “Each is dependent on the other. You have to have energy to produce water, and you need water to produce energy. The question is, what are the resources you are using and what are the resources you need?”

Savage hopes to buy back some of his cattle one day. But for now, the gas wells on his property keep him from losing his land. He is concerned about pollution incidents that have occurred nearby, presumably from gas drilling, especially since he pumps well water out of the Colorado River aquifer for domestic use. Despite this, he believes that “as far as pollution is concerned, the oil and gas industry is probably less of a threat than the general public,” due to people dumping chemicals and overusing fertilizer. Savage is also not too concerned about long-term water shortages.

“You’ll stop irrigating the golf courses before people die of thirst,” he said. “I think as water gets more expensive, as we get more and more people, we are going to have to get much more efficient in our use of water.”

Beef and Water

In another world, just 64 kilometers (40 miles) east of the historically gas-driven economy of Garfield, is Cold Mountain Ranch. Here, William Fales manages to keep his 300 head of cattle — which graze on a wide-open valley of alfalfa and irrigated grass — but not without a fight. Drought and the possibility of natural gas development in the nearby high country have Fales concerned about his water source.

“We rely on Thompson Creek water, which is right above here,” Fales said. “If that water is polluted, I do not want to be spreading it on our fields. And without irrigation, our farm would produce 5 percent of what it is producing today.”

Fales and his wife, Marj Perry, pride themselves on raising local grass-fed beef. The ranch has been in Perry’s family since 1924. Bill and Marj and their two daughters love ranching and being on the land. Located just under 2,400 meters (8,000 feet) in elevation and surrounded by ski towns of the Roaring Fork Valley, visitors to the ranch can admire the river’s source, 4,200-meter-high (14,000-feet-high) snow-packed mountain peaks. The bases of the mountaintops hug the valley’s arid landscape below. The Thompson Creek Divide area, which is also partially in Garfield County, is rich in biodiversity and natural resources. Three major forks drain from their Elk Mountain headwaters into the Roaring Fork River Watershed, including Divide Creek and the Crystal River.

“Look around, what’s not to love about it?” Fales asked. “I mean out here, working in a spectacular environment. I get a lot of pride in taking care of this land. I also take a lot of pride and get a lot of satisfaction out of growing good, healthy food.”

The family wants to have healthy cattle and is concerned that, if large-scale gas development goes into the heart of the summer high country, where the cattle graze, it will affect the cattle’s health. Fales helped start the Thompson Divide Coalition to try to protect approximately 42,500 hectares (105,00 acres) of federal land in the Thompson Divide area of northwest Colorado from the affects of gas drilling. The 12-boardmember coalition is comprised of local stakeholders and was formed in response to the Bush Administration issuing mineral leases in the Thompson Divide in 2003. Currently, 61 of the original 81 leases are active in the area. Some of the leases are in roadless areas and do not contain surface rules. Since then with the help of Fales the organization has made headway. Colorado State Senator Michael Bennet introduced the Thompson Divide Withdrawal and Protection Act to encourage ongoing conversation and provide opportunity for leases to be retired.

“The current price of gas in the West makes it totally uneconomical to develop these leases, but they are worried if they don’t do anything the leases will expire and they won’t have anything,” he explained in 2012. “It is just a spectacular yet somewhat fragile area that we are trying our damndest to maintain and protect the values it provides to this valley today.”

“The volume of water they need for fracking is mindboggling,” Fales added. “There is a limited supply, and it is over-allocated today and over-adjudicated today. So I do not think there is any extra water, which means they would have to haul it all in from someplace else.”

The drought in recent years has been stiff. Cold Mountain Ranch had enough feed last year because Bill and Marj managed their land well and had some leftover feed on reserve, but if the drought is as bad for another year, they will be forced to sell some of their cattle.

“The water is an incredibly valuable commodity to us. We just wouldn’t grow any feed without it,” Fales said, “This ground is totally dry, the area is too dry to grow much feed without water.”

Still, some ranchers, like Savage in Garfield County, felt they had no choice but to sell their cattle and replace them with natural gas drilling in order to keep their land.

A Wider Horizon

The region’s contrast between shale rock, dry desert landscape, and the vibrant green world of irrigated agriculture is most apparent from the air. Eco-Flight, a conservation organization, takes students up in a plane to see for themselves. In 2012, during their annual ‘Flight Across America,’ Eco-Flight flew over the natural gas fields of Garfield County, coal-fired power plants in New Mexico, and the Glen Canyon Dam.

Laurel Hagen, executive director of Canyon Lands Watershed Council explained that over-allocation of the Colorado River leaves others with none, such as Mexico. She posed a hard question. “How do we get [the water] to one population over another?” she asked.

“Right now, because urban populations are growing pretty fast, they are the ones who actually have the increasing demand for water,” she said. “We can conserve all we want, but eventually we are going to hit a wall if our population keeps going up,”

Basin diversions do not just include places like Denver and its suburbs but also big cities — like Los Angeles and Las Vegas — that hold water rights. Though cities are getting better at lowering their per-capita water demand, water use is still growing, because their populations are growing.

Calvin Davenport, 28, is studying environmental science and grew up in Grand Junction. He was on the Eco-Flight trip and describes himself as an outdoor recreationalist who loves to hunt, kayak, bike, and ski.

“I think everybody needs to be mindful of their consumption,” he said after the flight. “Just imagine everyone trying to live the way you want to live. We need to live within our means.”

Heather Rousseau, is chief photographer at The Herald in Jasper, Indiana, and a contributing photojournalist to Circle of Blue, where she interned in 2010. She can be reached at hkrousseau@gmail.com. Keith Schneider, Aubrey Ann Parker, and Brett Walton contributed to this report.

Back in the 70’s there were plans to add two more dams south of Parker on the river. Thanks to the tree huggers that plan went in the toilet. Maybe the general public would reconsider now. I was told that there would never be shortage if those two dams were placed. In addition to the water the recreation area would be a tremendous boom to the economy.

I have lived in the desert 41 out of my 59 years. I have always been a water conservationist. The biggest issue I see here in Las Vegas is that there are people that move in from areas that have plentiful water, and they plant non-indigenous plants that require too much to survive. People allow their water to run down the streets disregarding the penalties to do it. In other words they don’t care enough to think about the future. So far no fraking here. It should be stopped everywhere. Wasteful use of our precious resources.

On another note… you know about the Great Wall of China and the Hoover Dam… why not create a project on just as grand of a scale… consisting of dams and levies to capture melting snow and ice in the southwest region of what was once known as Lake Agassiz. A project of this magnitude would create jobs for decades, reduce downstream damage from flood waters every spring, provide the means for a Hydro-electric generating facility, the possibility for a multitude of lake area resorts, and create the benefit of a huge reservoir of fresh water that could be piped (another project) to the Colorado River to help replenish Lake Mead and save the southwest from the serious water shortage that it is only beginning to experience.

In your graphic, it states…”4,200 megawatts is the generating capacity of hydropower plants along the Colorado River”, which is true when the lakes before them are full and the rated capacity can be reached. As level drops, so does the static head, and the plants operate at a lower capacity. The hydroelectric plants can “overstroke” their wicket gates to allow more water to enter the turbine, and generate more power in response to lower lake levels, but these efforts are limited.