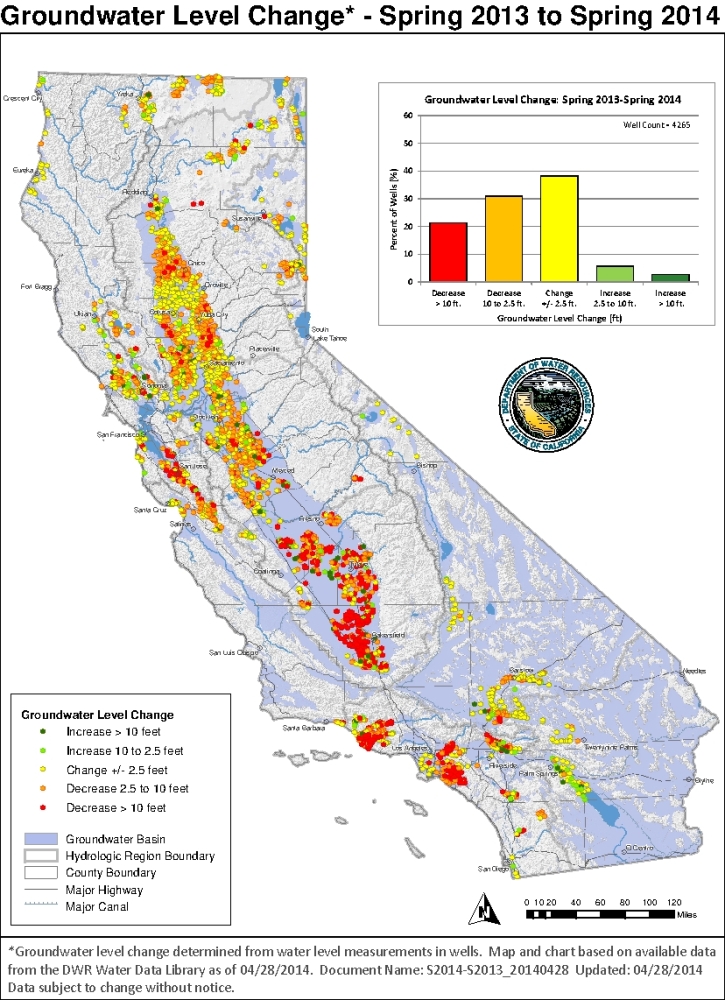

Most of California Groundwater Tables at All-time Lows, State Report Says

The biggest declines are in the San Joaquin Valley and in metropolitan Southern California.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

In a historic drought and with little river water being delivered in canals, Californians are taxing their groundwater reserves like never before, according to a state assessment released Wednesday.

All areas of the state are experiencing record declines in the water table, none more so than the San Joaquin Valley, an agricultural heavyweight that grows roughly half the nation’s fruits, vegetables, and nuts and uses a lot of water to do so – nearly half the state’s freshwater supply for just eight counties.

Aquifers in parts of the San Joaquin Valley dropped more than 30 meters (100 feet) below previous lows, while the water table in parts of the Sacramento Valley and in the basins of metropolitan Southern California are roughly 15 meters (50 feet) below old records.

The report, prepared by the Department of Water Resources (DWR), assesses four areas related to groundwater use:

- Groundwater basins with the potential for water shortages

- Groundwater basins that are not well monitored

- Farm fields that are not being planted (called fallowing)

- Land that is sinking, usually because of too much groundwater pumping (a process called subsidence)

Though not a stated goal, the report’s maps clearly show areas in which groundwater use is out of balance with sustainable extraction. These areas, if they do not quickly reverse decades of poor practices, may be candidates for state intervention. Governor Jerry Brown has said that if locals will not manage groundwater, the state will.

The governor requested the groundwater report in his January 17 drought declaration. A follow up report is due November 30.

Draining the Account

Groundwater is essential for cities in the Los Angeles Basin and vineyards in San Luis Obispo County, just as it is for the millions of acres of fertile land in the San Joaquin Valley. In an average year, some 40 percent of California’s water use comes from aquifers. In an exceptionally dry year – such as 2014 – groundwater’s share approaches 60 percent, though in some basins the figure is much higher.

The report describes which groundwater basins are most at risk for water shortages, where water levels have dropped most sharply, and where the data holes exist. The report is based on data from the state’s voluntary well-monitoring program, called CASGEM, which was established by law in 2009.

The CASGEM program has taken great strides, but significant gaps exist, according to the report. Only 169 of the state’s 515 groundwater basins are monitored.

But of those 515 basins, many are small or rarely used, thus not a leading concern. A handful of basins have a disproportionate value. The DWR identified 126 basins that account for 92 percent of the state’s groundwater use and serve 89 percent of its population.

Yet of these priority basins, three in 10 are not monitored under CASGEM, which, again, is voluntary. The data gaps are precisely the areas in which groundwater is being sucked out the fastest – the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys and the slip of coastal land from Santa Cruz to Santa Barbara. The sparsely populated interior lands from Owens Valley to the northern Mojave Desert are also included.

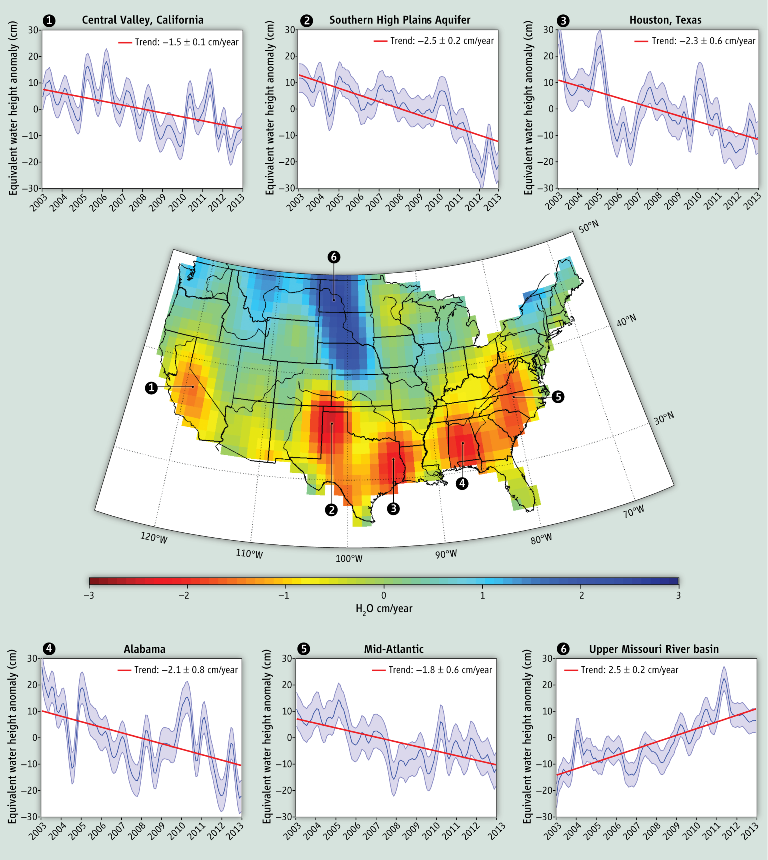

CASGEM data, however, shows only elevations, not volumes. Researchers at the University of California, Irvine have used satellite data to estimate how much water is being pumped. A recent study estimated that the amount of water stored in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Valley fell by 20 billion cubic meters, or two-thirds the volume of Lake Mead between 2011 and 2013.

Because it is an emergency source, groundwater use is expected to increase during drought, as more is withdrawn to compensate for paltry river flows. In wet years, the aquifers can recover. But the fact that most basins are in a long-term decline shows that groundwater use in California is far from an ideal balance.

Unsustainable use is a chronic problem, but for some basins a dry period leads to immediate threats. The DWR report identifies 36 groundwater basins at risk for water shortages in a drought. These basins have either a high reliance on groundwater (more than 61 percent of total supply) or use a lot of it (more than 0.61 acre-feet per acre). These at-risk basins are located on the coasts and in the Central Valley.

Fallowing and Subsidence

The DWR is working with federal agencies to assess these two aspects of the drought emergency.

Images from Landsat and MODIS, two NASA satellites, are being used to reckon how many acres farmers are not planting.

James Verdin of the U.S. Geological Survey is a collaborator on the project. He told Circle of Blue that researchers will compare current satellite reconnaissance with a trove of historical images. They will look for changes in “greenness,” which differentiates between fields of dirt and fields of, say, cantaloupes. That index will then be checked against statistical data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The method was being developed for later down the road, but the severity of the drought thrust the project forward.

“This wasn’t meant to be implemented in 2014,” Verdin told Circle of Blue. “But given the circumstances, we’re accelerating the work.”

The data will be used to vouch for counties as they apply for federal disaster assistance, Verdin said. The state may also use the assessment for divvying its own aid package.

Meanwhile, data from another NASA satellite – this one from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California – will be used to gauge land subsidence. Researchers will use InSAR, a satellite-based radar system, that measures changes in ground elevation.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!