Jerry Brown, Smart and Prepared, Responds to California’s Drought Emergency

Steeled by past drought, governor is reshaping how largest U.S. state uses and distributes water.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Three straight years of desperately dry conditions in California are igniting hills in walls of towering orange flames, turning reservoirs to sandpits, and causing residents across America’s most populous state to clamor for water.

Months ago the California drought established its ranking as one of the worst ecological emergencies in the United States since the 1930s, when an equally hot and dry era – helped by catastrophic mismanagement of farmland – turned Great Plains topsoil to dust. With each passing week without rain, though, the California drought is steadily crossing into new economic, environmental and governing frontier. It’s becoming a test of modern American democracy’s capacity to recognize change and to adjust, perhaps dramatically, a region’s water-rich economy and way of life to an unfolding era of scarce moisture.

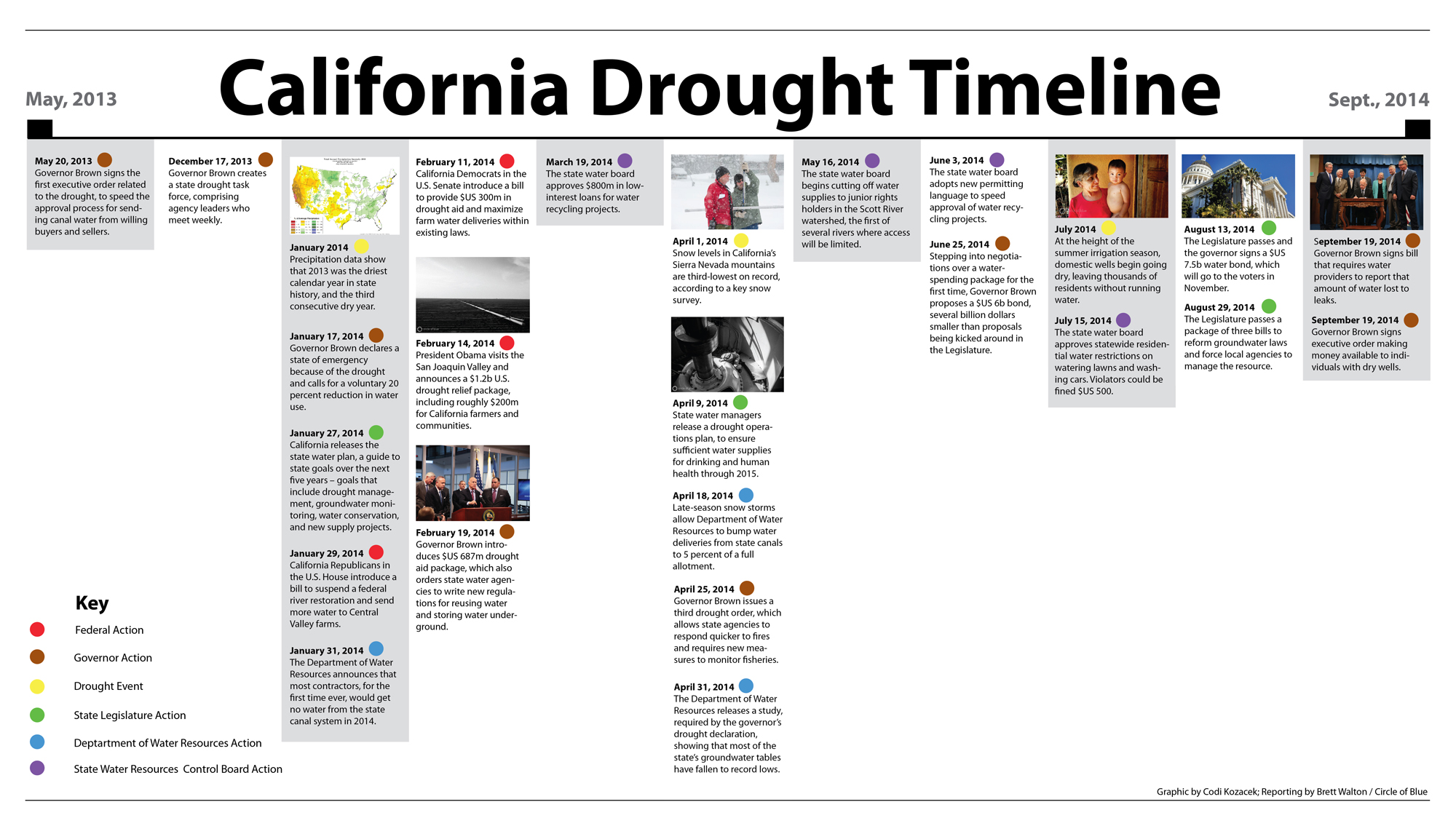

California’s Democratic Governor Jerry Brown understands that. Through a series of major actions – shepherding groundwater reforms and a $US 7.5 billion water spending measure through the state Legislature – and a host of less visible steps – improving lines of communication between state agencies and accelerating the drafting of new rules for reusing water – Brown is conducting a clinic on how to direct public investment and dispatch personnel to shift how California businesses and citizens respond to conditions of water scarcity.

In the process he’s enthused supporters and swayed critics. More significantly, if the drought persists through the winter Brown will become, arguably, the most important water manager on Earth.

“It is a tall order,” Brown said in his January 2014 State of the State speech, referring to the list of actions needed to respond to the emergency. “But it is what we must do to get through this drought and prepare for the next. We do not know how much our current problem derives from the build-up of heat-trapping gasses, but we can take this drought as a stark warning of things to come.”

Drought is difficult to prepare for, arduous to manage, and perplexing to assess. Scientists do not know exactly when the lean times will strike, how deeply they will cut, or when moisture will return. Lack of water leads a parade of ills. The risk of catastrophic fire increases. Some diseases, notably West Nile virus, spread more quickly. Without cleansing rains, pollutants and dust particles foul the air. Farm and recreation jobs evaporate. Given time, water scarcity works its way to other big water users – energy suppliers, municipal water systems, manufacturers, and eventually homeowners.

In its first three years, California’s drought has pummeled rural economies and society’s vulnerable – farm workers and small communities. If it continues, drought draws the rest of society into the corral of desperation. No leader, especially those accustomed to pleasing the crowd, relishes water deprivation, markets roiled by scarcity, and the decisions about supply and distribution that are sure to aggravate one group or another.

And yet Governor Brown manages the drought with political clarity that has impressed supporters with his steadfast attention to detail, yet left others, particularly farmers and farm workers, wondering why help from state government is so late in arriving.

“Jerry Brown has handled the drought extremely well in Sacramento – ‘inside the Beltway’ we’d say if we were in Washington, D.C.,” Arthur Kidman, a water rights lawyer working in California since the 1970s, told Circle of Blue. “Outside Sacramento there are significant forces he doesn’t have control over” – the powerful legal traditions of landowner rights to water, for example – “but inside Sacramento he has been masterful.”

Through executive orders and legislative cajoling, Brown has pushed Californians to use less water, albeit incrementally and imperfectly. He has pursued emergency actions for dry communities, identifying in January those most at risk of calamity and providing state assistance in finding alternative water supplies.

“Inside Sacramento [Brown] has been masterful.”

–Arthur Kidman, water rights lawyer,

Kidman Law

His declaration of a drought disaster, also in January, cut paperwork requirements and quickened agency response times. The state Department of Water Resources held back more water in reservoirs than usual, cutting water deliveries from state canals to record lows. Brown convinced the Legislature to direct local communities to write new plans that should lead to lower groundwater consumption, a historic change to water law in a state that has resisted government oversight of underground water sources.

Brown, known as a tight-fisted budget balancer, also isn’t afraid of spending money when warranted. The Legislature, at his urging, approved a $US 687 million emergency measure for food aid to farm workers put out of work by the drought, to finance work by utilities to fix leaks and make other improvements in water efficiency, and to halt declines in groundwater tables. Following that spending bill, Brown directed the State Water Resources Control Board in March to offer utilities $US 800 million in low interest loans for projects to expand or construct plants to recycle water.

The last ten months are an impressive record of achievement, evidence of a governor taking seriously the duties of governing. What Brown is orchestrating in California is distinctive, perhaps unique in the United States during this frustrating age of division. In most other states policy changes and investments necessary to adapt to new environmental conditions have been impeded by leadership fogged by the politics of austerity and ideology. The results are that the nation’s transport, water, and power infrastructure are reaching the end of their design lives and not being modernized, expanded, or replaced.

One critically significant advantage enjoyed by Brown is that he is supported by a state Assembly and a state Senate with Democratic majorities. A second advantage is that Brown is governing during a deepening emergency. The result is that he’s able to pull the levers of legislative and executive power to turn California in a new direction.

If the drought continues, more levers will be pulled. Brown, up for reelection in November, is almost certain to win a fourth term and retain his office. Ahead by 20 points in the polls, Brown’s biggest push is for passage of a $US 7.5 billion bond dedicated to water projects, which the Legislature approved in August and the voters appear likely to endorse. The spending measure, one-third of which is dedicated to storing water either behind new dams or underground in aquifers, targets future droughts. The bond provides money for recycling water, cleansing polluted aquifers, and increasing wetland habitat for birds and fish species.

Drought a Chronic Problem

Brown and his state know drought, deep drought. Water managers were nervous in 1977, the middle of Brown’s first term as governor. California’s rivers had never flowed with so little force, at least not in the eight decades of official recordkeeping. Lake Shasta, the state’s largest reservoir, had never been lower, setting a record that still holds today. A temporary pipeline was laid across the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge, spanning San Francisco Bay, to send water to suddenly dry Marin County.

“This is an era of limits and there are very hard choices to make,” Brown said in his opening address to a state drought conference in March 1977. It is a refrain he repeated in January 2014 when declaring the current drought an emergency.

Those two years – 1976 and 1977 – began a transformation of California’s water behavior. Brown created an office of water conservation within the Department of Water Resources. He advocated for more use of recycled water for cities and drip irrigation for farms, both of which are techniques for cutting water withdrawals from rivers and aquifers.

Plumbing codes were eventually revised as part of a statewide movement to drive down municipal water use. Results were swift and consequential, ushering in permanent changes. Water demand did not rebound after the drought. Owing to steep declines in the farm sector, total water withdrawals peaked in 1980, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

In addition, Brown commissioned a study of ways to improve state water law. One of the expert panel’s four recommendations was to strengthen groundwater regulations. That turned out to be a path to water conservation that few wanted to follow. The state, unwilling to cast away the belief of a property owner’s largely unfettered access to water beneath his land, was not ready to act. Then, as today, groundwater rescued the agriculture industry. Some 10,000 new wells were drilled in 1977, according to a state review.

Nonetheless, the shifts in water use were unmistakable and long-lasting.

“Jerry Brown, in his first two terms as governor, actually set in motion many of the programs that have mitigated the worst effects of the current drought,” Jonas Minton told Circle of Blue. Now the water policy adviser for the Planning and Conservation League, a green group, Minton was a staff member of the California Department of Water Resources during the late 1970s.

The momentum continued even after Brown left office in January 1983. Later that year the Legislature passed a law requiring urban water providers to submit plans every five years outlining how they manage supply and demand.

The drought of the 1970s, serious as it was, did not hold long enough to compel the state to revise core principles of water policy and tradition. The drought was certainly bad – Lake Oroville, the main source for state-operated canals, was lower in 1977 than today – but it was short-lived. Ground-soaking rains in the winter of 1978 refilled the reservoirs, and eased the urgency.

Wait, Wait, Act

Today, in a state whose population has grown by 70 percent since 1977, Brown finds himself back in the seat of power where he is again confronting forces of tradition and the convoluted plumbing of one of the world’s most highly engineered water systems.

As governor, the 76-year-old Brown has the authority to declare state emergencies, which he did for the drought on January 17. Characteristically, he promised as much help as he could give and no more than he thought necessary.

“Don’t think that a paper from the governor’s office is going to affect the rain,” Brown said after making the declaration. “We are doing what we can do in terms of water exchanges and we’ll do other things as we get down the road. That seems to be probably enough, from my point of view.”

As each dry month passed, the governor, who did not respond to Circle of Blue’s request for an interview, acted with steps appropriate to the steadily drying conditions: Money to help small communities connect their water lines to larger systems with more secure sources of supply. Measures to curb urban water use and the authorization of fines to give the orders teeth. New rules to speed the transfer of water between buyers and sellers, and to facilitate use of recycled water.

“He thinks unconventionally,” Phil Isenberg told Circle of Blue. Isenberg is the vice-chair of the Delta Stewardship Council, an advisory group for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the state’s most important water body, and he was mayor of Sacramento during the 1977 drought. “The governor is really smart. He thinks about the end goal instead of getting lost in the details of the fight.”

The governor began 2014 with two goals: 1) act quickly but deliberately in doling out emergency aid and 2) begin repositioning California’s water laws and infrastructure so that the state is more resilient to future drought and deluge. But to achieve them he would need the Legislature’s help.

Brown initiated the former by establishing in December a state committee to coordinate drought efforts and by declaring a drought emergency on January 17. Too soon, some argued but in retrospect the correct move, said Peter Gleick, president of the Pacific Institute.

The second goal followed two paths, both of which crossed the Democratic-controlled Legislature. One path pointed toward a new bond measure to invest state money in water storage projects, pollution cleanup, and conservation. The other sought reforms in how groundwater, an imperiled resource and 60 percent of the state’s water supply this year, is managed. Local agencies will be required to exercise firmer control on groundwater use.

To do so, Brown divided the labor. He let members of the state Assembly and Senate debate the bond measure. Nearly one dozen proposals popped up, ranging in cost from $US 6 billion to $US 11 billion.

On groundwater, Brown enlisted the help of the California Water Foundation, a nonprofit led by the aptly named Lester Snow, former head of the state Department of Water Resources. A handful of public hearings were held in farm towns and city centers to note the voice of the people.

Brown, meanwhile, was largely silent on both fronts. Observers in Sacramento wondered if the governor even knew what he wanted out of the endeavor. Still, throughout the spring, he waited.

As legislative deadlines approached this summer, Brown acted.

He threw his weight behind a much smaller bond – just $US 6 billion. When it was apparent that he needed Republican support to clinch the two-thirds majority required for passage, he added $US 700 million more for storage projects, to appease representatives of the Central Valley, the heart of the state’s $US 43 billion agriculture economy.

“Water is central to our lives, our wildlife and our food supply,” Brown wrote in June in a letter to California residents. “Our economy depends on it. We must act now so that we can continue to manage as good stewards of this vital resource for generations to come. But we can and must do so without returning California to the days of overwhelming deficit and debt.”

The final bond, which passed 77 to 2 in the Assembly and unanimously in the Senate, totals $US 7.5 billion in state spending in the coming years, more than one-third of which is dedicated to water storage. Green groups hope this means injecting water into underground basins, while farm groups are keen on more dams. Others fear that funding in the bond will be used for the governor’s $US 25 billion proposal to build a pair of tunnels to move water through the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the state’s imperiled water hub. Those divisive battles are yet to be fought but they will likely be on the horizon. Opinion polls released in late September show 58 percent of voters approving the bond.

Brown’s tactics on the water bond recall his Zen training learned while in Japan in the early 1980s – action only when necessary.

“He stayed out of the legislative discussion until the debates were at the point of exhaustion and that was masterful,” said Kidman, the water rights lawyer.

The groundwater bills did not have the same legislative unity. They passed without any Republican votes, needing only a simple majority. But they did pass and Brown, unlike in 1977, had important allies.

Kidman attributes the success of the groundwater legislation to the transformation of a key interest group, the Association of California Water Agencies, or ACWA, which represents 430 water providers in the state. Formerly a linchpin of farm interests, ACWA has recently seen more influence from urban water agencies. Gaining ACWA’s endorsement reflected a shift in sentiment. Groundwater regulation was now supported by the public as well.

“‘Significant’ understates it,” Kidman said, referring to the importance of the groundwater legislation. “It’s a sea change of extraordinary magnitude. When you have the organization that speaks for all water agencies in California speaking in favor, that changed the politics.”

The reason for the shift was a better understanding of the gravity of the situation, said the Pacific Institute’s Peter Gleick. “New science changed minds,” Gleick told Circle of Blue. “New information about how serious the problem is shocked a lot of people. That led to support from groups long opposed to groundwater law.”

Gaps in the Response

Not everybody is so mesmerized. Many of the governor’s actions will not produce additional water supplies or result in management improvements for years or decades. The groundwater law requires local agencies to rein in groundwater use by 2040. Those whose lives are altered now by a lack of water are less enthused by the pace of change.

Drought is hardest on farmers, who use the lion’s share of the state’s water; on the rural poor, whose wells have gone dry at record rates this year; and on fisheries, which are facing disease and death as rivers are too low and too hot to support normal populations.

Understandably, representatives of these groups are most critical of the state’s response. Some of the criticism is warranted. The state, for example, was not prepared for the drinking water catastrophe occurring in the San Joaquin Valley, where aquifers have dropped so low from ravenous farm demand that thousands of residents do not have running water in their homes because of dry wells.

“Help is not coming soon enough,” Gladys Colunga, a Tulare County resident whose well went dry in June, told Circle of Blue. “Can’t they get something moving quicker? This is an emergency situation. We’re the lost world here.”

While the state in January identified community systems at risk of running out of water and gave them money to drill new wells or to connect with nearby systems, individual well owners had no such safety net. Not until mid-September did the governor issue an executive order addressing the valley’s well crisis.

Social workers saw the frustration, but they acknowledge that the wheels of bureaucracy are turning quicker than before.

“The state’s response has gone from glacial to fast. Not quick, but quicker,” Ryan Jensen, an organizer with the Community Water Center in Visalia, told Circle of Blue.

Still, because the number of dry wells is unprecedented, the state’s reaction is an improvisation.

“We’re making it up as we go,” Jensen said. “I don’t think anyone was well prepared for this. We’re all working together to develop an emergency response. It’s frustrating for people living day to day with this.”

The Political Art of Conservation

Even with apparent gaps, Brown has had an outsized effect on the course of the state’s water history.

His role may grow larger if the coming winter is dry again. Early hopes of heavy snows fueled by a strong El Nino weather pattern have faded.

State officials are not making weather predictions, but they are approaching the coming year with more forethought. Mark Cowin, director of the California Department of Water Resources, said last week that a dry winter and wet winter are equally probable at this point, but the department wants to be better prepared for potential catastrophe than it was ten months ago.

“Last year in January, we did a quick, hurried assessment of potential human health and safety needs across the state,” Cowin told the Metropolitan Water District, the state’s largest municipal water wholesaler. “We want to do a little more diligent planning for the potential impacts and hot spots that we might expect in 2015, so we intend to begin working with all of you on that. We’re also working with state and federal agencies on getting a jump on how we will define the issues and try to reach the balance between water supply and environmental protection, water quality, all of the issues that we worked so hard to balance last year.”

If so, more cuts in water use will be necessary. It is an opportunity for Brown not just to govern but to lead, to sell Californians on the idea that using less water is not an economic and cultural catastrophe, but a challenge and a benefit. Evidence from the Great Plains, where demands also exceed supply, is proof that a dynamic, persistent champion for change is paramount.

“The water supply is limited and demands are limitless,” said Isenberg, of the Delta Stewardship Council. “Because of this we will have enduring problems with water in California. There’s no way to guarantee all the interests all the water they want every year. Most people would not want to hear that.

“We have to get used to living within our means. How you convince people to buy into that is the art of politics, and Jerry Brown is a damn good political artist.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Brown + tracking = no foresight or sincere concern for California

Is this article a spoof ?

Anyone that knows the water history in CA. would know what is being told in this article is not so.

The people who vote these mental midgets into office are just going to have to drink “Brown” water.

I lived in Californistan for 60 years before escaping. I won a water conservation award in the 70’s and work in other countries that want solutions, not illusions. Get out before the whole state goes down.

What took the Brown man so long to do something? I think he smoked to much of something while partying with Linda Maria Ronstadt?

Have you heard of the Blues Brothers? The Brown brothers, both Willie and Jerri have created a CA. that is dying….the voters deserve what they have and what they will get in the future.

Thanks for the humor

G

.Brown “now” understands that California is in a drought?? He should be left in a dry field in the Central Valley for 6 months to fend for himself so he will truly “understand” the problem!