Jolted by Reality, Colorado River Water Managers Plan for Persistent Drought

Unprepared for more years of drought, basin states work to preserve Lake Powell.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

The severe risks of an extended drought in the Colorado River Basin – a shutdown of hydropower generation, functionally empty lakes, and restrictions on water use – are forcing the basin’s seven states to consider unprecedented changes in how they manage a scarce resource.

Still in the earliest stages of negotiation, two remedies have emerged, both of which seek to fortify Lake Powell, the nation’s second largest reservoir, and preserve its capacity to generate electricity and supply water to the 40 million people who live in the watershed.

One strategy is an operational revision: release more water from upper-basin reservoirs during drought emergencies. The other option would cut demand: ask – or perhaps pay – farmers to stop growing crops in order to save water. Both approaches are technically and legally feasible, according to those involved in the discussions and outside experts.

–Don Ostler, executive director

Upper Colorado River Commission

“We’ve never had to do this before because we never planned for this degree of low water storage,” Don Ostler, executive director of the Upper Colorado River Commission, an administrative body, told Circle of Blue. “We want to plan for extreme hydrology the likes of which we have never seen.”

In these parched times, the Colorado River conundrum is a problem common to water officials from Austin to Sacramento.

Several exceptionally dry years in some of the nation’s largest economies and fastest-growing regions have prompted responses never before taken, as water managers dole out smaller sips from an emptying drinking glass.

Rice farmers on the Texas Gulf Coast, for instance, will receive no irrigation water for the third consecutive year and the third time ever. Reservoirs upstream near Austin are so low that water rights may need to be recalculated based on the new hydrology.

In California, smothered by a record drought and with snowpack just 32 percent of normal, neither cities nor farmers will get water from state canals this year.

Across the American West, farmers are tapping underground water sources at unsustainable rates to offset the lack of water in rivers and lakes.

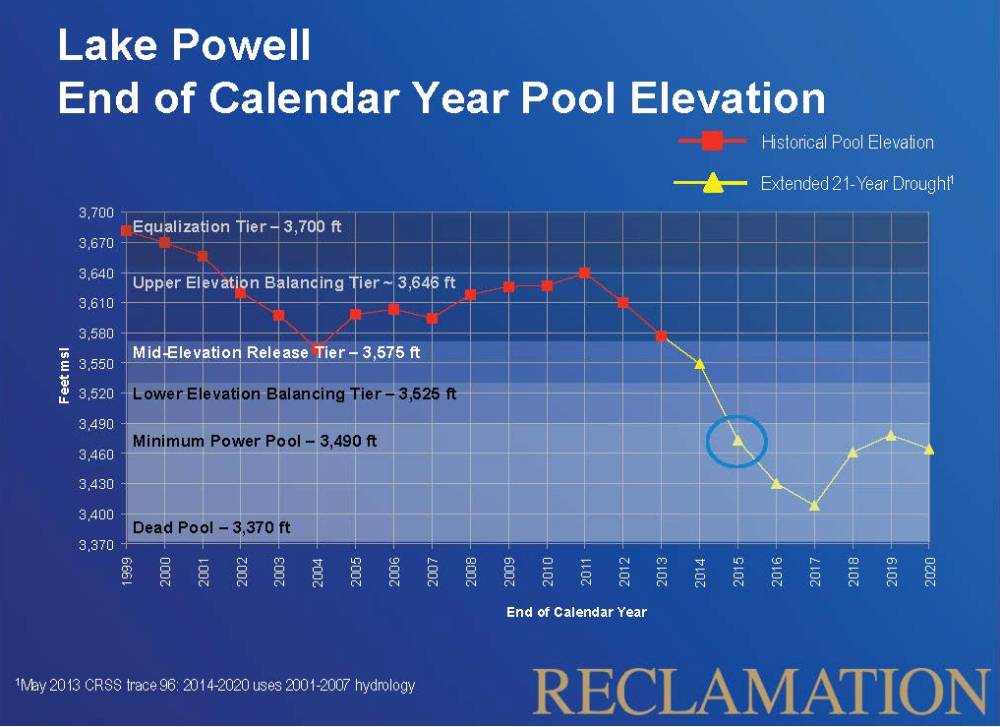

Meanwhile in the iconic Colorado River, flows have been above average in only three of the last 14 years. If the rest of the decade follows a similar hydrological trajectory, “dramatic problems emerge rather quickly,” said John McClow, Colorado’s representative to the Upper Colorado River Commission.

McClow told Circle of Blue that the basin states used computer simulations last June to replicate the 2001 to 2007 river flows, a rather dry period, from 2014 until the end of the decade.

By 2017, the modeling showed a 20 percent chance of both Lake Powell and Lake Mead dropping too low to generate electricity. Mead would also fall below the first water supply pipe for Las Vegas. (The gambling mecca does not like those odds. It will complete a $US 817 million back-up intake by next spring.)

“There’s a significant chance we would be in dire straits pretty fast,” McClow said, referring to a continuation of current drought conditions. “Nothing in our toolbox could respond to those circumstances that quickly.”

Forging New Tools

An interstate agreement nearly a century ago divided the Colorado River for legal purposes into an upper basin and a lower basin. The two basins operate somewhat independently, and each is holding its own drought discussions.

The four states of the upper basin – Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming – have been most forthcoming about their emergency plans.

The upper basin wants to prevent a call on the river, a circumstance in which the four states are unable to meet their legal obligations to send water downstream to Arizona, California, and Nevada. A call has never happened.

The upper basin also wants to keep Lake Powell’s surface elevation from dropping below 3,490 feet, the point at which hydropower generation from Glen Canyon Dam, which forms the reservoir, would probably stop. Lake Powell has never tested that limit, a theoretical threshold. Today, Powell’s surface elevation is 3,574 feet, having fallen 60 feet in two years.

Glen Canyon provides as many as 5.8 million people with a portion of their electricity. Revenue from electricity sales helps pay to operate the dams. It also underwrites measures to reduce salt in the Colorado River and revive fish habitat.

To keep Powell from draining, one option is to release more water from reservoirs located higher in the basin: Flaming Gorge, in Wyoming; Navajo, in New Mexico; and a Colorado cluster known as the Aspinall Unit.

These Rocky Mountain reservoirs evaporate less water than Powell, located in Utah’s arid canyon country, said Malcolm Wilson, chief of the Bureau of Reclamation’s water resources group, which operates the reservoirs. But that does not preclude a shift in operations.

“There’s nothing to say we couldn’t release more water than we have to sustain Powell,” Wilson told Circle of Blue, stating that the interests of the upper basin and Reclamation align, both wanting to keep the dam’s cash register ringing.

–Doug Kenney, senior research associate

University of Colorado

McClow noted that recreation and environmental constraints would need to be respected. Each of the higher-elevation reservoirs has an endangered species in its watershed, he said.

Along with the reservoir shuffle, upper basin negotiators are debating what a farmland fallowing program would look like. More questions – Who pays for it? Which lands are targeted? – than answers exist now, McClow said.

Doug Kenney, a water policy expert at the University of Colorado’s Natural Resources Law Center, said he saw no obvious legal problems with the two options.

“As long as they don’t try to be too picky about who owns that water, then I think it’s entirely realistic,” Kenney told Circle of Blue. “If they want to be picky, then all sorts of legal issues and potential problems come forward.”

Kenney said that ascribing ownership to the water begins to resemble the selling or transfer of water rights across state lines, a bête noire for the basin. Better, he said, if the water is not earmarked and simply flows downstream.

Ostler, the river commission’s executive director, said that the upper basin would like to have a plan finalized by the end of the year.

“We hope it will sit on the shelf,” he said, wishing for wetter days ahead.

Lower Basin Plays Its Options Close to the Vest

The threat of shrinking reservoirs is also on the minds of water managers in Arizona, California, and Nevada, the three lower basins states that rely on Lake Mead, Powell’s bigger and older brother. The three states signed a water-shortage agreement in 2007.

If the surface elevation of Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir, drops below 1,075 feet, water restrictions for Arizona and Nevada kick in. (California, a political behemoth, negotiated itself no cut.) Bureau of Reclamation forecasts anticipate a first-ever shortage as soon as 2016.

If the lake continues to wither, the shallowest water intake for Las Vegas will suck in only air. Eventually the decline will halt hydropower generation at Hoover Dam, one of the largest power stations in the West.

All of which are reasons for water managers in the lower basin to worry. But none of the representatives that Circle of Blue contacted offered many details about their drought planning.

“We’re certainly having discussions about existing drought and contingency planning for an ongoing sustained drought,” said Colby Pellegrino, who handles Colorado River issues for Southern Nevada Water Authority, the state’s largest water utility. “But we’re not to a point where we can say what those options will be.”

Tanya Trujillo, executive director of the Colorado River Board of California, also demurred and declined to comment.

Pellegrino did say that the lower basin states are using hydrology models used in the Bureau of Reclamation’s Colorado River Basin study, a comprehensive supply and demand assessment published in December 2012.

That study assessed water use through 2060, but the current drought discussions take a narrower view. Pellegrino said the lower basin interests are looking at options through 2026, the year that the shortage sharing agreement expires.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Or they could save half a million acre-feet per year (8% of the Colorado’s annual flow) now lost to bank storage and evaporation from Powell and drain the sucker. That water is worth more on the open market than the value of the electricity the damn dam generates, and it would be better to store it at Lake Mead, where the walls are igneous rock.

I keep returning in my mind to the Circle of Blue forum held a few weeks ago about the California drought, in which Mike Young, an Australian who has been central to creating a new water paradigm and management system for Australia, participated. He was here in Tucson, Arizona last week and he expanded on ideas he shared at the forum, titling one talk something like “Missed Opportunity for Arizona?” The missed opportunity is failing to educate the public, press and policy makers about the comprehensive legal and institutional reforms that have taken place in Australia, South Africa, and elsewhere–well summarized, by the way, in Brian Richter’s new book, “Chasing Water: a Guide for Moving from Scarcity to Sustainability.” The book puts forth seven principles for sustainable water management, beginning with setting a limit on total water consumption and adhering to the core principle of hydrological integrity and ecological thresholds. In the Circle of Blue forum, Mike Young questioned whether we can manage water in the West without making this fundamental shift in how we view and manage water.

As plans for managing the Colorado as well as water in the West in these times emerge, it’s vital that we turn to examples that seem to be gaining traction elsewhere, beginning with the key core understanding/principle about hydrological integrity and ecological thresholds.

It is a misnomer to say that the 40 million people live in it’s watershed. I would hardly call San Diego a part of the Colorado’s watershed, for instance. San Diego has it’s own San Diego River watershed, and moves water from the Colorado through a nearly 90 year old aqueduct.

The more that we all become aware of the watersheds we actually live and work in, the more that we will understand that localizing water collection and use – supported primarily by rainwater capture and graywater reuse, obviating stormwater management, is the way to become responsible and engaged water users.

great article!

major water concern and fraught with all sorts of decisions,

ethical, political, from farmers/agriculture, capital/corporations,

communities, drinking,cooking,cleaning, bathing…etc.

it’s not that difficult to harvest rain water from roofs, parking lots,

and any place we can think of not letting it go to waste

…and not pollute, frack or destroy what we have.