North American Fossil Fuel Boom Raises Risks From Expanding Oil and Gas Transport Network

Surge in oil and gas production has seen more spills that are harming water supplies.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Until two years ago, when the National Wildlife Federation pointed out their presence, the twin oil pipelines beneath the fast-flowing channel that connects Lake Michigan to Lake Huron were like nearly every other piece of North America’s energy-transport network. The 61-year-old steel pipelines — owned and managed apparently without incident by Enbridge Inc., a Canadian pipeline operator — attracted virtually no attention from Michigan’s citizens or its state government.

Those days are over. A remarkable and unexpected surge in continental production of oil and natural gas is reshaping domestic and global energy markets, dropping prices for gasoline, raising employment in the energy and manufacturing sectors, and prompting civic concerns about the risks to water, land, and communities.

The North American fossil fuel bonanza also is directing more attention than ever before to the management, safety, and disruptive changes in the pipeline and rail systems that ship oil and gas to market.

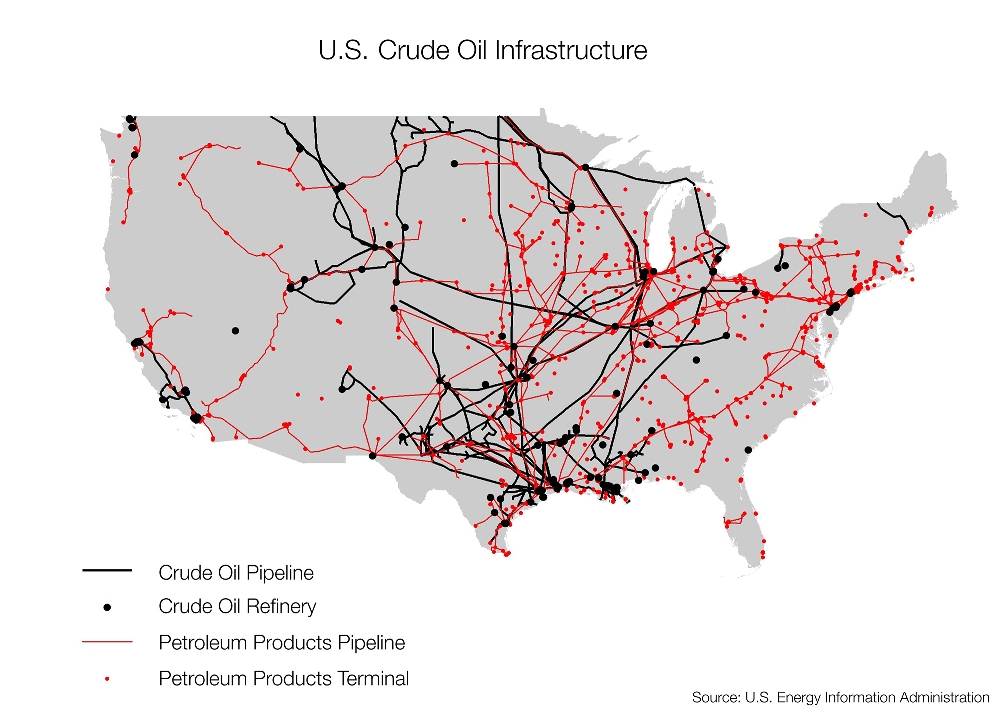

The continent’s new energy reserves — from Alberta and Saskatchewan to the Dakotas, Montana, Colorado, Texas, and the Eastern United States — are located in areas that are not well-connected to the conventional markets, refineries, and customers, developed in 20th century, or to the growing 21st-century roster of terminals that are currently under construction for exporting fuels.

–Carl Weimer, executive director

Pipeline Safety Trust

Oil and gas, in effect, need more ways to get to market. Energy companies are engaged in a continental campaign to fashion a pipeline and rail network to match the new geography and the new supply.

Piece by piece, the energy industry is assembling an expanded circulatory system for moving oil and natural gas, but there is no systematic national plan for developing these energy corridors in ways that minimize risk.

The route of the Keystone XL pipeline, which would link Alberta to the Texas Gulf, is the most visible example and a focus of national protest (the proposed route crosses a sensitive aquifer in Nebraska that citizens and the state’s governor want to protect). But the same challenge has arisen elsewhere, bringing tensions and danger to small towns in North America’s empty quarters.

Over the last two years, trains carrying oil from Canada and the Dakotas have exploded in Aliceville, Alabama; Casselton, North Dakota; and Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, causing loss of life and property. In 2010, a pipeline carrying oil to a refinery in Detroit from the tar sands region of Alberta ruptured in southern Michigan, spilling nearly 1 million gallons of sticky crude into the Kalamazoo River. In 2012, the National Wildlife Federation called the Mackinac Straits pipelines a “sunken hazard,” prompting activist campaigns in communities from across the Great Lakes region to remove or reinforce the lines.

“Our big frustration is that, to a high degree, the planning of how to get the oil from Point A to Point B is left up to the pipeline and energy companies,” said Carl Weimer, executive director of the Pipeline Safety Trust, an advocacy group in Bellingham, Washington, in an interview with Circle of Blue. “In the East Coast, for example, you see multiple companies trying to develop lines going to the same location. There doesn’t seem to be any federal government oversight, no agency asking if two lines are appropriate in this location or four. Because of this, more communities are affected by construction.”

Mammoth New Pipeline Capacity

The scale of that construction is astounding. Industry analysts forecast that an average of nearly $US 50 billion a year will be spent by 2025 to create pipeline and rail networks that connect natural gas hot spots in British Columbia and Pennsylvania and oil fields in Alberta, North Dakota, and Texas to refineries, processing plants, and coastal export facilities. Older pipelines are being enlarged or the direction of flow is being reversed to accommodate the unexpected bounty of hydrocarbons wrought by hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”), tar sands, and other new extraction techniques. Where pipeline capacity is insufficient, rail transport of crude oil — a more expensive and, in some ways, riskier alternative — has ballooned.

Construction crews are hustling to keep pace with demand. As many as 28,968 kilometers (18,000 miles) of new, expanded, or refurbished crude oil pipelines — enough to string two Earths like a chain of pearls — will be put in the ground in Canada and the United States by 2018, according to IHS Global, a consultancy.

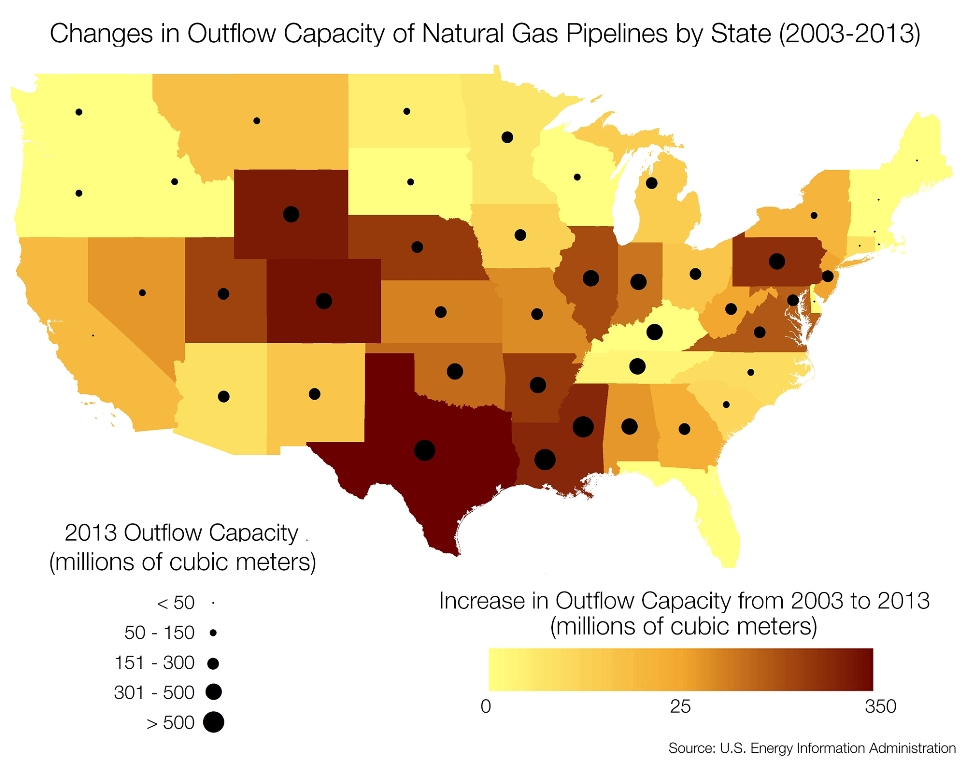

Jeff Wright, director of the Office of Energy Projects at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the U.S. regulator for natural gas networks, told a federal pipeline advisory committee in October that a “tsunami of new pipelines” is imminent, yet growth is already occurring.

Since the boom began in 2008, the U.S. crude oil system has expanded by 20 percent. Some 5,549 kilometers (3,448 miles) of crude oil pipelines were added to the U.S. system in 2013 alone, a move which increased the national length by 6 percent, according to federal government data.

The country’s railroads are seeing comparable growth. Analysts estimate a two-year production backlog for new rail tanker cars, designed with stricter safety standards.

“[The map] has been reshaped entirely,” said Ken Medlock, an energy economist at Rice University’s Baker Institute, in an interview with Circle of Blue. “Most people 10 to 20 years ago would have told you that energy infrastructure would be developed to move product from the coast [inward], because we’d become an increasing importer of both crude oil and natural gas. And today, you’re actually seeing the exact opposite begin to emerge — we’re going from the middle of the country to the coast and trying to find ways to export.”

But as the broadest expansion in decades of fuel-transport capacity unfolds in Canada and the United States, the public is becoming increasingly aware of the potential for leaks, fires, and water contamination. Citizens are concerned about how well pipelines and rail transit are being designed and operated. For instance, the Straits of Mackinac’s Line 5 is one of many dozens of pipelines — both old and new — from British Columbia to New England that are being looked at in a new light.

According to Tom Miesner, a 35-year veteran of the pipeline business and principal of the consulting firm Pipeline Knowledge & Development, the challenge for the industry is two-fold:

- the outward growth of cities brings more people closer to pipelines that were once located in fields or forests when they were originally built

- a pipeline’s proximity to water sources, where the environmental damages from a spill and the cost of cleanup are significant

“For crude oil pipelines, the highest risk is where you have people and water, because that is usually where the consequences of a release are greatest,” Miesner explained.

A New Era of Oil and Gas

Construction of oil and natural gas pipelines in Canada and the United States has been swift and disruptive, with investment increasing since 2010 by 60 percent to $US 89 billion in 2013, according to IHS.

“By 2015, just a year from now, the landscape of major U.S. crude oil pipelines will have almost no resemblance to the picture that existed in 2005,” IHS asserted in a December 2013 report.

The record levels of spending for pipeline construction are designed to keep pace with the head-spinning growth in fossil fuels production. For the time being, the mismatch between production and transport capacity is growing wider and more apparent.

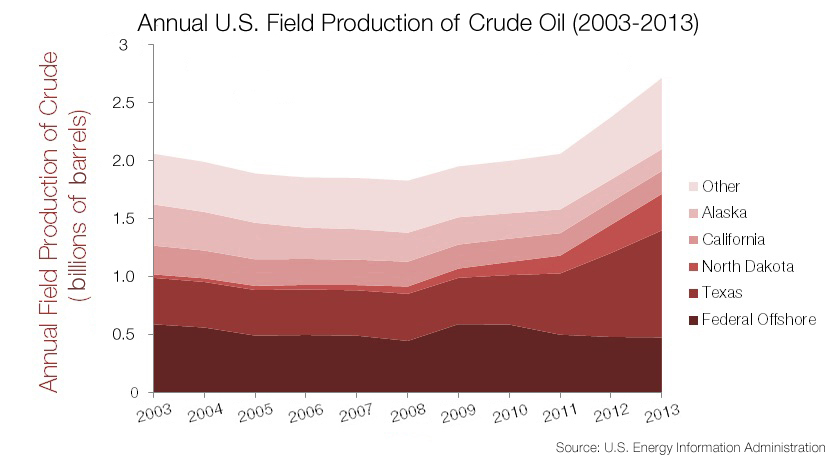

Since 2009, U.S. natural gas production rose 22 percent, while crude oil production jumped 67 percent, according to the Energy Information Administration. In the same time, production of heavy crudes in Canada — including the tar sands — increased 70 percent, according to the National Energy Board. President Obama’s chief economic advisor compared the rise in U.S. oil production this decade to discovering a new Iraq at home.

In oil and gas patches without adequate pipeline infrastructure, rail transport has grown exponentially. In just two years, exports of oil from Alberta to the United States by rail have shot up 813 percent. Rail shipment of crude oil within the United States is nearly off the charts, a 3,654 percent increase since 2009.

Opponents of the Keystone XL pipeline — the most visible of the proposed delivery routes — believe that stopping the project will help prevent the tar sands, one of the world’s most expensive and dirtiest sources of oil, from being developed.

That logic, though, is being turned on its head by rail transport. Oil is not waiting for new pipelines, noted Medlock, the energy economist. It is hitching a ride southward on the rails.

“If you put the clamps on one part of the market, the capital will find a way to facilitate development, if there’s really an opportunity there,” Medlock said. “And that’s exactly what’s happening.”

In the Bakken oil fields of North Dakota, for example, production outpaces the region’s pipeline capacity by 450,000 barrels a day. What cannot fit into a pipeline is shunted to a growing fleet of rail terminals and then out onto the tracks in 100-car trains.

Meanwhile, new rail terminals to unload these trains and new tracks for them to run on are being proposed for riverside and maritime locations from California and Washington to New York. Increases in rail traffic are creating congestion where they cut through towns and cities. More oil by rail, for example, means less space to move a record grain harvest in the Midwest to market.

“It’s not an either/or proposal — to ship or not to ship oil,” said Mark Barteau, professor of chemical engineering at the University of Michigan, in an interview with Circle of Blue. “What you’re going to do without pipeline capacity is transport fuels by less desirable means.”

A Game of Risk

By “less desirable,” Barteau means moving oil by rail. The rise of rail — as well as the expansion of older pipelines — raises questions of risk and of inadequate infrastructure, points underscored by several high-profile accidents recently involving oil trains and old pipes.

Risk itself is often misunderstood, or at least not understood by the general public in the way technical experts define the term. Those who analyze risk see it as a combination of two variables: both the likelihood of an accident and its consequences. The chances of any given pipeline breaking are small but the consequences are significant if the rupture happens in a suburban neighborhood or under Lake Michigan.

Crude oil pipelines pose a greater risk to sources of water than natural gas lines because of the cost of cleaning up liquid fuels. Though none of the experts interviewed for this story could provide data comparing rail spills to pipeline spills — a persistent problem for nearly all pipeline risk calculations — they agreed that rail transit results in more accidents than pipelines but smaller volumes spilled.

Two recent accidents underscore the risks of rail. A year ago, a train carrying oil from the Bakken fields in North Dakota hit a derailed grain train and crashed, spilling 1.5 million liters (396,000 gallons) of oil onto the prairie. In July 2013, an explosion following the derailment of a train also carrying volatile oil from Bakken killed 47 people in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, and spilled at least 100,000 liters (26,400 gallons) into the Chaudière River.

In both cases, the trains were using an older model of tank car that is easily punctured in an accident. Federal regulators in Canada and the United States have recommended phasing out the old cars, but a complete turnover in stock will take years. The U.S. regulator for oil and gas transport, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, proposed a two-year timetable, but industry representatives are asking for at least seven years to transition to safer models.

Pipeline spills, which are less frequent than rail accidents but often result in larger releases, which can pose a greater environmental risk. The worst was the 2010 spill of 3.2 million liters (845,000 gallons) of diluted bitumen into Michigan’s Kalamazoo River, a spill that grew larger when the Enbridge operations staff misinterpreted emergency signals and failed to shut down the line. The heavy oil dropped to the river bed where it is more difficult to remove, the reason why pipeline transportation of diluted bitumen poses a higher risk to water than other forms of oil. Cleanup costs have passed $US 1 billion, and the National Academy of Sciences is now studying the environmental consequences of diluted bitumen spills.

In other cases, soft regulation has led to spills. An Exxon pipeline across the Yellowstone River in Montana ruptured in July 2011, spilling roughly 179,000 liters (47,250 gallons) of oil and causing $US 135 million in property damages. Investigators found that flood waters had scoured the river bed and exposed the metal. While pipeline operators are required by federal regulation to bury pipes at least four feet deep, they are not required to maintain that depth of cover over the lifetime of the pipe, even though rivers are dynamic earth-movers and exposure to debris in open currents can led to a collision and rupture.

Older pipelines are another concern. Half the pipelines in the United States were built more than 50 years ago. A March 2013 spill in Arkansas, a case that federal regulators are still investigating, came from a pipeline roughly 60 years old. Michigan’s U.S. Senate delegation along with state officials has questioned the safety of the 61-year-old Line 5 through the Straits of Mackinac. Enbridge insists they are safe and increased the amount of oil running them by 10 percent last year.

Age does not necessarily pose a greater risk. As long as they are properly maintained, older pipelines can operate without incident for decades – as is the case with Line 5, which has never leaked, according to Enbridge. But newer pipelines have the advantages of technological progress. They are made of better materials, are manufactured under tighter tolerances, and have better protection against corrosion, noted Barteau, who chaired a National Academy of Sciences committee on the pipeline transportation of diluted bitumen. But, as with any part of life, there are still risks.

“Pipelines are certainly not perfect,” Barteau explained. “They do leak. Sometimes detection of leaks does not occur immediately, and there is human error in operating them, like in Marshall, Michigan [where the Kalamazoo River spill occurred]. So we need to improve the system at all points, not just by putting tougher materials into the ground.”

Yet spending money on tougher materials does matter, Barteau said.

“The basic problem in this country is that we don’t want to pay for infrastructure,” he lamented. “We can’t keep putting pressure on what we have until it turns to rust and dust.”

A Data and Regulatory Gaps

Determining the condition of the nation’s pipelines, however, is not so easy. For one, important data are missing. Reliable statistics on the number of minor leaks and near failures — cracks that should have been detected before reaching such a state of disrepair — are not available, said Oliver Moghissi, director of the Materials and Technology Center at DNV GL Columbus, an energy consulting firm.

Pipeline companies are supposed to keep detailed records of inspections, defects, and maintenance, but they are not required to keep such records for all pipelines nor are they required to submit them to regulators, said Weimer of the Pipeline Safety Trust.

The data that are reported reveal divergent trends. For example, the number of significant incidents for hazardous liquid pipelines — a category that includes spills that result in death, hospitalization, fire, or damages above $US 50,000 — declined for two decades only to rise again in the last five years.

“Everyone is scratching their heads,” Weimer said, referring to the increase in accidents. “Is it aging infrastructure? A matter of too many pipelines built too fast? We have no conclusion.”

Local Concerns

The perception of risk is magnified for communities in the path of rail lines and pipelines, argues Moghissi, because the communities are often not in control of the project. Those decisions are made at higher levels of government.

But local governments are increasingly using the few tools at their disposal. New policies and regulations pop up almost daily as local and state governments struggle to yoke an industry pushing pell-mell for more production and more lines to carry it to market. The Appellate Court in New York, for instance, ruled in July that local governments can block hydraulic fracturing for natural gas under home rule land-use regulations, while the city council in Vancouver, Washington passed a resolution opposing an oil terminal at a nearby port on the Columbia River that would handle 360,000 barrels per day from rail cars – almost half the capacity of the proposed Keystone XL pipeline.

In Michigan, state government regulators also are responding to public pressure on Line 5. Opened in 1953 as part of an oil network that skirts the Great Lakes, the pipes under the Straits of Mackinac were moving light crude across Michigan in the 1970s when the United States became the world’s top oil producer.

The oil continued to flow through the line during three decades of decline, as U.S. production fell to half its peak. Now North America is again the world’s center of oil and natural gas growth, and communities see the lines under the Mackinac Straits as a threat to the waters.

Aware that a spill in the Straits of Mackinac would set back a thriving fishing industry and tarnish one of the state’s top tourist destinations, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) earlier this year requested from Enbridge operation and maintenance records for Line 5, as well as information about the composition of its oil deliveries.

“Even though we don’t have regulatory authority over the pipeline, we have a constitutional duty to protect Michigan’s natural resources,” Brad Wurfel, Michigan DEQ spokesman, told Circle of Blue. A state task force is reviewing the documents and will offer recommendations by March 2015 for responding to a spill.

Land and water advocacy groups argue that a task force, while an encouraging first step, alone is insufficient. FLOW, an organization based in Traverse City, Michigan, that supports protection of natural resources for public use, is part of a coalition of like-minded groups that want the state to assess the potential harm from a Line 5 spill and exercise greater oversight over the pipeline.

“As things stand, Enbridge holds all the cards,” Liz Kirkwood, FLOW’s executive director, told Circle of Blue. “We want to open up the process and get the state to evaluate the pipeline and make decisions in full disclosure.” Those decisions, Kirkwood said, could range from restrictions on the type of fuel carried in the pipeline to a decommissioning and re-routing.

FLOW will present its public-trust argument to the task force in December. For now, the state is poring over the substantial amount of information Enbridge turned over, said Wurfel, who asserted that the department is “feeling more confident” about the condition of the pipeline than before. Still, the department wants to prepare for the worst.

“We have to assume that somewhere down the road a spill is going to happen,” Wurfel said.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Thank you Brent Walton and CoB for the article. Not only should the State of Michigan open up the process to review and consider the alternative routes that would avoid the high magnitude of harm and health threats if there is a spill in the Straits of Mackinac, the public trust doctrine, incorporated into state law — the Great Lakes Submerged Lands Act — demands authorization, so that alternatives must be considered, and findings of no impairment assured. It should also be understood that Michigan’s current administration is wrong that this is a federal regulatory matter. The federal government regulates safety of a line. Michigan holds title and sovereign control of the bottomlands and waters of the Great Lakes in public trust for the public, the beneficiaries of the trust. The state has a duty to prevent harm or impairment of Great Lakes or public and riparian uses that depend on them. State ownership and control can never be relinquished to private or other persons or entities. It is false to assume that an old pipeline without incident, at least none reported, under the Great Lakes is safe. There have been and are — just today, ironically — leaks along Line 5. Importantly, prudent state-of-the-art risk analysis demands that if there exist alternative routes with lower potential magnitude of harm, the high magnitude harm routes or sites like the Great Lakes, Line 5 under the Straits of Mackinac, Kalamazoo River, and other water crossings should be rejected.

those of us who live in rural areas through which pipelines are slated to go are also having a hard time hearing our lives dismissed as less “consequential”.