San Antonio Pipeline Continues Texas Water Rush

America’s seventh-largest city debates a pipeline project worth billions as the second-fastest-growing state faces more demands for water in its third year of severe drought.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

A champion of municipal water conservation in the United States is about to open its wallet for an expensive pipeline to increase its supply.

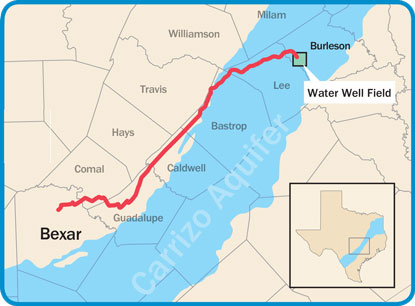

The San Antonio City Council is expected to approve on Thursday a 30-year, $US 3.4 billion contract to buy water from a private developer. The Vista Ridge project, which includes a 229-kilometer (142-mile) pipeline from the Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer in Texas, will boost water supplies for the nation’s seventh-largest city by 20 percent when it comes online in 2020.

–Greg Flores, spokesman

San Antonio Water System

Nowhere in the United States — not even in desperately parched California — is the scramble to build new water pipelines more evident than in Texas, where the hottest, driest year in state history in 2011 awoke many communities to the prospect of water scarcity.

“After 2011, a lot of communities realized they didn’t have the supplies needed to make it through a multi-year drought,” Greg Flores, San Antonio Water System spokesman, told Circle of Blue. “That realization will lead to future competition for water, because cities are now more aware. Cities are not only competing with each other, they’re competing with agriculture, bays and estuaries, industries, and oil and gas.”

In Texas, still reeling from the drought, Circle of Blue found at least a dozen water-pipeline projects under construction or completed within the last five years — and there are many more still on the drawing board. Aware of the increasing demands in a state that is expected to add 20 million people by 2060, San Antonio is likely to enter into the most expensive water contract in its history.

“There are a lot of needs in Texas, and we think that locking in water today makes sense,” Flores said.

Texas Cities Search for Water

Spooked by a record dry spell three years ago — a drought that is still evident in the state’s depleted reservoirs — and fearful of being left at the table with an empty glass, cities in the country’s second-fastest-growing state are eager to build. Even the Legislature is opening its wallet for cities in Texas. Last year, lawmakers created a $US 2 billion water fund with surplus money from oil and gas revenues. Low-interest loans from the fund will finance both water-conservation initiatives and water-supply projects that are included in the state’s $US 53 billion water plan.

More water transfers are taking place in Texas than ever before, according to Andrew Sansom, executive director of the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment at Texas State University. Sansom believes that the pace will pick up even more once the water fund is opened to applications next year.

“Everything is accelerating in urgency because of the drought,” Sansom told Circle of Blue. “People are settling into the notion that drought could last for many years.”

Thinking like financial managers, cities want a “diverse portfolio” of water sources. San Antonio is one of those cities on the hunt for alternatives. By 2030, the city’s water utility plans to have at least a dozen distinct sources of supply — desalinated brackish water, recycled wastewater, and imports — all for a utility that until the late 1990s relied on a single source, the Edwards Aquifer.

Frequently the search for new supplies leads underground. Texas has given out more permits to water in rivers and streams than is actually available, Sansom said, which is prompting the run on groundwater. Water beneath the land is a private property right in Texas, and groundwater management districts can do little to prevent it from being sold, even to users outside the basin.

San Antonio is not an outlier. It is one of many Texas cities from the Panhandle to the Gulf of Mexico that are spending money on pipelines. For example:

- Amarillo, the second-largest city in the Panhandle, completed an $US 86 million groundwater pipeline in 2011 after its main reservoir dried up.

- Corpus Christi, home to one of the country’s largest ports, broke ground on a $US 160 million pipeline this spring to tap into longstanding rights to water from the Colorado River.

- San Angelo — a plains city of 95,000 — completed a 100-kilometer (62-mile), $US 120 million pipeline to the Hickory Aquifer this summer and will have treated water flowing by next year. The city acquired the rights to the water in the 1970s but only recently needed to develop the source.

“You have to have water for economic vitality,” Ricky Dickson, director of San Angelo Water Utilities, told Circle of Blue. “Without water, you don’t have anything.”

Indeed, economic arguments often hold sway when it comes to justifying a big budget outlay for water infrastructure, even if the supplies are not immediately needed, as is the case in San Angelo, which will operate its new facility at just one-sixth of capacity initially, Dickson said.

Public-Private Partnership for San Antonio Water

San Antonio had a long courtship with Abengoa Vista Ridge LLC, the project’s developer.

Three years ago, San Antonio Water System (SAWS), the water utility, solicited bids from developers that wanted to supply the city with water. SAWS has won numerous national awards for its water conservation programs, but utility leaders think that the time is right to increase supply. Developers were happy to oblige. SAWS received nine applications.

SAWS then selected three finalists but rejected them in February 2014 because each of the proposals was too risky or too costly. Some of the groundwater districts targeted in the applications were grumbling about water being exported out of their basins. If they moved to curtail pumping, SAWS did not want to be on the hook for a pipeline that did not hold water. Instead, the utility decided to expand its use of brackish water, which could be made drinkable by removing the excess salt.

Then, Abengoa Vista Ridge, which submitted the highest-ranked proposal, came back with a sweetened offer. It would take on the regulatory risk, meaning San Antonio would only pay for water that would be delivered. An automatic annual cost increase of 2 percent was ditched, as was a $US 5 million annual fee. SAWS approved the project in September 2014.

Abengoa Vista Ridge is a partnership between Abengoa, a Spanish engineering firm that will build the pipeline, and BlueWater Systems, a Texas group that negotiated some 3,400 individual water leases in the Post Oak Savannah Groundwater Conservation District and tied them into one package to fill the pipeline.

In the end, the pipeline will deliver 61.6 million cubic meters (50,000 acre-feet, or 16 billion gallons) per year, enough to supply 162,000 homes. Totaling 616 pages, the $US 3.4 billion contract includes $US 864 million to construct the pipeline plus fixed payments for the water itself, which will be some of the most expensive in Texas — between $US 1,852 and $US 1,959 per acre-foot depending on interest rates for the loan that Abengoa Vista Ridge still needs to secure. The cost of operating the project and the electricity to run it will add roughly $US 350 per acre-foot at today’s prices. The pipeline contract alone, not including SAWS other projects to expand supply, will increase rates by roughly 16 percent, according to the utility.

Meanwhile, SAWS has capped its interest rate exposure at 6 percent. If the costs of financing the project are any higher, Abengoa pays the balance. After 30 years the assets, including the pipeline, will be transferred to SAWS.

Long-time San Antonio residents might remember a deal, proposed decades ago, for the city to buy water from nearby Canyon Lake. In 1976, the City Council voted against the deal, which would have fixed the price at what is now a considerable bargain.

When asked if buyer’s remorse motivated the Vista Ridge deal, Flores, the SAWS spokesman, said, “Absolutely. The cost of water is only going up.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Using the word “drought” to describe what is happening across the southern US has built in the assumption that very arid conditions are the rare condition and that conditions will bounce back to normal conditions that are wetter. Given that human-induced climate change from, mainly, relying on fossil fuels for our energy is leading generally to a northward expansion of the subtropics and so drier conditions on average, the region seems likely to become more and more arid, with very wet conditions (e.g., from occasional very wet hurricanes, tropical storms, etc.) being the rare year. Like San Antonio’s leaders, some regions in Australia have been having a multi-decade drought, and then had a wet year, suggesting to some leaders that the drought had been broken; this seems very doubtful in that the Southern Hemisphere subtropics are also expanding poleward, pushing the storm track southward. Again, saying that they have been in a drought rather than that the climate is overall becoming more arid, is very likely optimistic–and misleading about what lies ahead; after all, we don’t say that the Sahara Desert, once green and vegetated, is suffering a 6000-year drought. San Antonio is a wonderful place, and it would be nice if the proposed pipeline provides a long-term solution, but I’d urge being quite cautious, dare I say conservative, in thinking about the future of water for the region.