‘Transformational’ Water Reforms, Though Wrenching, Helped Australia Endure Historic Drought, Experts Say

California, in the third year of its worst drought ever, faces challenges similar to those of Australia. A panel of water policy experts and Circle of Blue journalists questioned whether the nation’s most populous state has the resolve to enact similar reforms.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

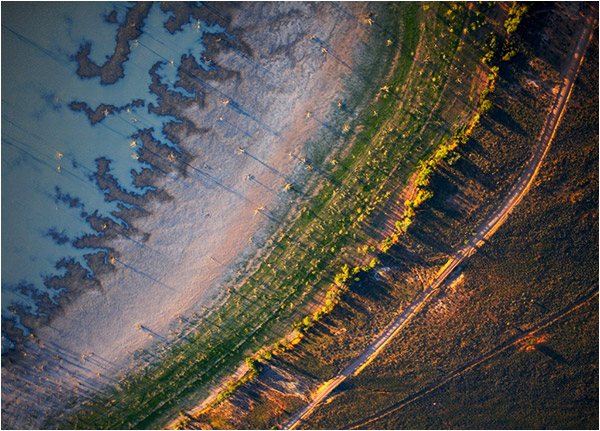

Ten years of implacable dryness in the 2000s staggered Australians, who saw the River Murray, the country’s longest waterway, fail to reach the sea, while a deep social depression spread through rural farm communities that did not have enough moisture to raise a crop.

Yet, even as the rains failed for more than a decade, Australia avoided complete economic calamity, thanks to comprehensive water reforms and a drastic reduction in urban water use.

The country’s willingness to throw out a well-worn water playbook and rebuild laws, behaviors, and governing bodies could be an inspirational model for California, now in the third year of a record-breaking drought, and for other water-scarce regions of the United States.

These were the main conclusions from a Circle of Blue interactive conference call on March 18 that featured a panel of water policy experts who have worked or lived in Australia or California and nearly 400 callers who dialed in from around the world to share their knowledge and concerns.

A Systematic Transformation

Australia’s current water code and its engineered water system of pipes and treatment plants would be unrecognizable to the men who framed the country’s original water laws more than one hundred years ago. Water leaders today realized that the old legal system, based on land ownership, did not provide enough flexibility when water was scarce.

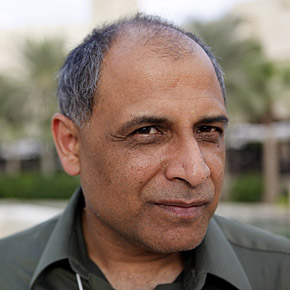

“The entire water allocation system, which evolved in the previous century was inappropriate for the future,” said panelist Michael Young, professor of water and environmental policy at the University of Adelaide.

–Michael Young, professor

University of Adelaide

Australia made several significant policy changes. The federal government, to the initial chagrin of the states, placed a firm cap on the amount of water drawn from rivers and lakes. The government split water allocations into long-term entitlements and tradable annual shares.

Australia’s leaders discarded the concept of beneficial use, Young said. Beneficial use, a foundation for water law in the western United States, requires that water be used or forfeited, resulting in wasteful farming practices. Notions about who was first to use the water and thus had the oldest rights were abolished. The federal government also handed out at least $US 10 billion to farmers to improve irrigation systems and ensure their support for the transition.

In effect, one of the world’s driest countries fully embraced a market system that allows water to be moved quickly and precisely between users in order to maximize the water’s economic value.

In the drought’s worst year, for example, when the total volume of water available to farmers was cut to one third, the value of irrigated agriculture remained at 70 percent of normal.

“Transformational reforms work,” said Young, who had a hand in designing the new system.

Urban centers also underwent a transformation. Brian Richter, lead scientist for water markets at the Nature Conservancy, said that Australia’s cities, through education campaigns and price increases, were able to cut water use by 35 to 50 percent.

Heather Cooley, water program director at the Pacific Institute, emphasized the differences in urban water use between Australia and California. The average Australian household uses 227 liters (60 gallons) per person per day, while the average California household consumes twice that amount. Cooley added that 80 percent of Australian household have a dual-flush toilet, a model that uses the least water. These conservation and efficiency measures, she argued, are the cheapest ways to reduce demand and thus increase supplies.

The panelists agreed that Australian cities rushed to build expensive facilities to remove the salt from sea water. Cooley said that coastal cities built six desalination plants at a cost of $US 10 billion, even as water conservation programs produced significant water savings. Residents are still paying for these desalination facilities, though only two are currently operating. The rains returned and once-empty reservoirs refilled.

“These are cautionary tales about the need to pursue cheaper alternatives first,” Cooley argued.

Cooley said she sees a different tone in California’s water discussions, as the drought is helping the public see the value of water.

But the true test is how society responds, asserted Keith Schneider, Circle of Blue’s senior editor, who has reported on the competition for water, food, and energy from four continents.

“Societies have one gear: forward,” Schneider said. “The Earth is telling us we need to change. We’re being forced to embrace different ways. We have the capacity to adjust, but can we do it quickly enough?”

California is slowly turning in that direction – the state is debating new groundwater regulations and is considering spending between $US 7 billion and $US 9 billion on water projects – but no panelist was confident that the state is willing just yet to take the formidable leap that Australia did.

“California Drought – Lessons from Australia”

The California drought, now in its third year, looks to be a significant test of the capacity of residents, farmers, businesses and governments to ensure the state’s water security.

Transcript: Circle of Blue Conference Call – March 18, 2014

Transcription by Ashleigh Lauren Hall

Heather Cooley

Water Program Director

Pacific Institute

Professor Michael Young

Gough Whitlam and Malcolm Fraser Chair in Australian Studies, Harvard University

Chair in Water and Environmental Policy, University of Adelaide

Honorary Professor, University College London

Dr. Robert Wilkinson

Director, Water Policy Program

University of California, Santa Barbara

Brian Richter

Chief Scientist of Water Markets

Nature Conservancy

J. Carl Ganter

Managing Director

Circle of Blue

Member, World Economic Forum

Global Agenda Council on Water Security

Keith Schneider

Senior Editor

Circle of Blue

Brett Walton

Reporter

Circle of Blue

J. Carl Ganter: I’m J. Carl Ganter, director of Circle of Blue. Today we’re going to dig deep into California’s water situation and learn from Australia’s experience with its long, really painful drought, in many way. First, as most of you know, Circle of Blue is the leading platform for original front-line reporting about the growing competition between water, food and energy, globally. We like to ask big questions and spot important trends. We like to be on the ground with the best traditions of journalism, science and data to understand some of the world’s most complex stories. Recently we reported extensively on the water/energy challenge in the U.S. through Choke Point – US, and then in China, India and Mongolia in partnership with the Wilson Center’s China Environment Forum. We’ve just released Choke Point: Index. It’s an index exploration of the competition between water, food and energy in a changing climate. We look at three key regions in the U.S. We look at the Great Lakes, the Ogallala Aquifer, and California’s Central Valley. Stay tuned tomorrow, when we’ll publish a very cool data dashboard about California water supplies. These reports and thousands of other pieces are on the site at 99.198.125.162/~circl731.

We’ve had support from the Rockefeller Foundation, the Wege Foundation, the Alpern Foundation, and our partners at the Columbia Water Center, Wilson Center, University of California, Click View, Google Research, Pacific Institute, and many others on this project. Maestro Conference is providing the platform for this call. We have a really powerful line up for you. First, though, Brian Burt, who is CEO of Maestro Conference, who is our host, is going to give us a few words about this era of collaboration, and about how we’re bringing you all together today. Brian?

Brian Burt: Great, Carl. It’s a real pleasure to be here. I live here in California, in Oakland, just five minutes across the Bay Bridge from San Francisco. When Carl asked me – he’s used some of the technology, we’ve done it before – when he asked me if we could collaborate around this event, I just got fired up. Certainly, in my circles, and many of you, I can see, are here in California, a lot of talk about this issue.

Today we’re going to have the chance to move into the type of journalism that Carl’s interested in, and has done. I know in the Great Lakes and in China, which is really moving beyond reporting into collaboration and problem-solving. I’m really excited to get a chance to hear from you. We’ll do that in a few minutes. We’ll create some groups to work together on issues of your interest at the end – during the last half of the two-hour segment. You can definitely look forward to moving beyond hearing from the panelists to really participating, sharing what you see, sharing your opportunities and the opportunities you see for collaboration in your questions.

We’ll have a lot of interactivity. Carl asked me to move from beyond a technology role to a speaker role when we got to talking about this. I just wanted to say for me, when I look at California, and really the world in general right now, we have such a tremendous capability to cooperate. We now have instant, global communication that’s basically free. The fact that at any level of organization we can collaborate, track statuses, we can create a market. But there’s something really unique about this moment. Our institutions are, in many ways, dinosaurs from a past era. I think there’s a real moment for people to look around and say ‘What can we really do?’, and I don’t know the specific solution. But I know that California has the resources to really build some sort of cooperative mechanism. To not be wasting our water in some places and starving for it in others.

Obviously we’re not going to change, and instantly make it rain, although with global climate impact we might make there be a lot less water in the future, but we’re not going to change on a seasonal basis how much water falls from the sky. We can change how we use it. I think there’s a tremendous opportunity here to collaborate, to really think creatively, to really get people involved in different ways then they’re used to. I know that’s what Carl came to us and said we wanted to do.

We’re here to help you all that are involved and have a stake in this interest, have a lot of expertise, help come together and create some ideas for solutions and then start to engage the stakeholders in those concepts. I’m really excited to be here and to be part of this. It’s an issue I care deeply about and what Circle of Blue is doing.

J. Carl Ganter: Thanks so much, Brian. As Brian said, we’re here to create collaboration around water. The big challenges and big ideas. We have, for any of those just joining us, we have exceptional panelists. You’ll hear from them in just a few seconds. We really want to hear from you first. We’ve got several hundred of the best and brightest on the line, or at least those who carved out time to dial in and participate and learn, and really – I hope – share some great ideas and also where we need to be going next. We’re journalists. We’re always all ears. For a few moments, we’re going to put you into small groups and our panelists are tuned in, they’re here now. Brian, you can tell us how that’s going to work. We’ll come up with a few questions for our panelists, and then we’ll kick them into sharing their experiences and then we’ll come back to a Q&A, and then wrap it up with some other participatory fun.

Brian Burt: Absolutely. We’re going get into break-outs of about 5. We’re pretty well distributed folks between academia, people in policy, the media, research, and “water buffalos,” which obviously is a term for people who have a real interest in this topic. We’re going to go ahead and create a small break out group – the panelists are going to get a chance to hear from you so they can really address the panel to you who are actually here and participating today. What this is going to be like, is we’re going to get quiet on the main line, and you’ll just go around and say your name, where you’re calling from, and your organization. So, I’m Brian, in California, from Maestro Communication. We’ll just go around to see who else is there. Then we’ve got two topics for you. What are the areas that you see for collaboration? Where do you think we can collaborate? We need to measure it here, create a market here, with this kind of policy or this kind of outreach. We want to hear from you on your ideas on collaboration. Secondly, what are your questions? What are the questions you have for each other, what are the questions you have for the panelists? We’re going to do that for 3 or 4 minutes, to give the panelists a chance to hear from you, give you a chance to meet each other. When you hear the sound of the tone, you will be in these break out groups, and you’ll just go around and 1. Say your name, where you’re from and your organization, and 2. You’re going to discuss collaboration – what are the opportunities you see for collaboration – and what are the questions you have. You’re now in your break out groups. We’ll get quiet here on the main line. Then we’ll hear from the panelists who have had a chance to hear from you. At the sound of the tone you can go ahead and begin.

[Break Out Groups Occurred.]

J. Carl Ganter: That was excellent. It was fun to hear how quickly people dive right into this issue. Now that you’ve had a moment to get to know each other, let’s get to know our panel. We’re going to start and just do a quick introduction, and then we’ll have the comments from our panelists. We’ll start with Circle of Blue senior editor, Keith Schneider. He’s been covering the issue with us all over the world. He’ll give us a big picture overview of our recent findings. Keith will be followed by Brent Walton. He’s one of our lead reporters here at Circle of Blue. He’s been covering California’s drought and other major water scarcity stories, particularly in the U.S. Then we’ll hear from Heather Cooley. She’s director of the Water Program at the Pacific Institute. Heather will be followed by Dr. Bob Wilkinson. He’s director of the Water Policy Program at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Then we’ll hear about ecosystems and water markets from Brian Richter. He’s Chief Scientist of Water Markets at the Nature Conservancy. Finally we’ll have Mike Young; he’s the chair of the Australian Studies program at Harvard University and chair of water policy at the University of Adelaide. Of course, he’ll bring us the Australian perspective and probably some new lines on California. A little later, too, we’ll have a cameo appearance from Upmanu Lall. He’s director of the University of Columbia’s Water Center.

We’ll move really quickly. After the initial introductions and briefing from our panelists, we’ll open to questions, too. Of course, we’ll be doing a lot more of these calls around national and international “choke points,” as we call them.

Let’s get started. Let me introduce Keith Schneider.

Keith Schneider: Thanks so much Carl. Interesting call. Really important story. This is Keith Schneider. I’ve been an environmental reporter for decades now, and I’m senior editor with Circle of Blue. My role is to try to give us a global perspective on what’s happening, and then link it back to California and the West. I’d like to shout out to the Wilson Center and Jennifer Turner, because much of the work I’m going to describe here couldn’t have been done without her and her colleagues. Jennifer, if you’re on the phone, thanks so much.

What we’re seeing in California, and what we’ve seen in Texas, with a persistent drying is occurring around the world in many of the world’s most important energy development zones and many of the world’s most important food production zones. We know this because we’ve had the privilege of actually being there. We’ve had a very high IWT quotient in our reporting – that is “I Was There.”

In 2008, we were in Australia. We’re going to learn more about what’s happened since then, but we did a project called The Biggest Dry in Australia, in its prime food-growing region, the Murray-Darling Basin, and saw the consequences of 12 years of very persistent, severe drought and we talked about the kinds of policy changes which we’ll learn about and how the farm sector in Australia dealt with it. When we were there, we also saw the collapse of the southern hemisphere’s largest rice production industry, and the consequences of that, globally, were significant. It was a factor in raising rice prices and grain prices, which was a factor in raising food prices which itself was a factor in the Arab Spring of 2011. These kinds of severe meteorological and hydrological eruption have important consequences in the daily lives of millions of people.

We’ve been to China. China’s Yellow River is one of its largest grain-growing areas. One out of every five bushels of grain comes from the Yellow River, which is a nine-province drought area. 70% of its coal, which is China’s primary production – energy source also comes from the Yellow River. The Yellow River is losing moisture. We were able to determine that the Yellow River will be 20 billion – 20 billion cubic meters short of water by the end of this decade without changes in their energy production and energy use and grain production practices. China’s done a pretty good job in water conservation, but it’s not going to be good enough given how fast they’re growing, how much energy they’re using, and there needs to be there – we’ve found – a change in vector in how they approach it.

We’ve been to Mongolia. The South Gobi Desert is a very important new energy development zone. Not much water there. A lot of it is ground water. There is a contest between the traditional herding culture in the South Gobi and the energy production sector there.

We’ve been to India. I’ve been to India twice now, three times. India’s energy production zones in the eastern part of India, the hydrological cycles have changed, and their food productions zones in Punjab and Hariana in the northwest have also changed. This has produced a cycle of risk in which – India also has public policy which gives its energy and its water free to its farmers who produce massive surpluses in the northwest parts of the country. The eastern part of the country can’t produce enough coal to fire fuel the number of coal fire power plants.

All of this is a sort of preamble to what we’re learning in Texas and California. Both have faced very significant drought. California is now in the third year of a drought that scientists say is the worst in 500 years. We’re seeing all sorts of political kinds of dimensions that are changing. We’re seeing scrambling on how to prepare for both the short term — $2 billion in short term symptomatic relief made earlier this year by the federal and state governments to deal with the short term financial symptoms. Now, $7-8-9 billion in water bonds are being considered to consider the long terms kinds of changes in practices, policy, technology in water storage and water transport in California. What we have found in our work globally is that things are related. Things are connected. Drought is not just a California-centric problem. It’s a global problem. And these kinds of calls and this kind of reporting is essential to how we share ideas and move on. Thank you.

I’m going to introduce our very fine young reporter, Brent Walton. He’s covering this closely from his Seattle base and he’s been in California numbers of times, and this morning posted a brand new story about the contest for how to spend $7-9 billion in bonds that going to be on the ballot in November. Brett…

Brett Walton, Circle of Blue reporter: Thanks, Keith, and thanks everyone to do this today. The last time we had one of these calls about a month ago in mid-February. I was down in Sacramento where there were lots of interesting conversations going on. Water scarcity will do that. It will bring people to consider ideas they hadn’t considered in the past. That’s what we’re seeing in California right now. This is not California’s first major drought. Nor will it be the last. California has a notoriously variable climate. What we’re seeing now, though, is different in one regard in that the drought now is hotter. California just set a record for the warmest winter in 119 years of record keeping. Even though precipitation has gone down now quite a bit, it’s being made more severe by this increase in heat. This drought has caught state officials off guard. It really underscored how reliant California is on a handful of large storm systems that come across the state between November and the end of March. As we stand right now, we’re going into the very end of the winter rainy season. So we have a better idea than we had a month ago about the state’s water supply condition. There’s still a possibility of more rain, but it looks like the forecast for the next few weeks is dry. We’ll still be going into the summer irrigation season with reservoirs at about 40 percent of capacity. We will be going in with snow pack which is about 30 percent of its historical normal. These are very low conditions. What we’re seeing in California is coincidence with this drought and major discussions about what to do for California’s water future. There’s a widespread agreement that what California has now – the water system it has, its water supply behavior is not compatible with a warmer, dryer future. Three conversations that are going on in the state that I’ll summarize here, but I’m sure we’ll get to more detail with our panelists.

One is the water bond, which I keep mentioning. There’s a discussion in the state legislature right now of how much money to put on a water bond which will be on the November ballot. It will probably be in the range of $7-9 billion for all manner of water infrastructure, water conservation, stream restoration, to ensure that the state’s supply is more reliable and the rivers are healthier.

The second is a Bay Delta Conservation plan, which is Governor Jerry Brown’s proposal that the state spend $25 billion on a pair of tunnels to increase water reliability across the state and improve the delta’s ecosystem, which is at the heart of the state’s water politics.

The third thing that people are discussing is ground water reform. Ground water is an essential part of California’s water supply, making it about 40% of what the state uses. In a drought, ground water is supposed to be the emergency relief, which is what people are trying to do right now. The problem is that ground water has been abused and neglected over the years, poorly regulated. So the state is talking about how to pool its ground water policies into a more sustainable future.

These are the three things I’m sure we’re going to talk more about. And now I’ll move on to Heather.

Heather Cooley, water program director, Pacific Institute: Great, thank you. I want to thank Circle of Blue for holding this webinar. This is a really important topic, and one that deserves attention beyond what we can cover in this webinar. Certainly this is a good start. The topic of the webinar is a broad one. I will focus on what we can learn from Australia’s experience with water conservation and efficiency, especially in urban areas. If time permits I’ll briefly touch on their experience with sea water desalination and what we might learn from that here in California.

First on urban efficiency: Australia has made tremendous progress on water conservation and efficiency. In urban water use, in Australia, is far lower than it is here in California. Consider that in Australia, average household water use is less than 60 gallons per person per day. In comparison, in California, average household water use is two times that at 120 gallons per person per day. Further, again looking at household water use, about fifty percent of household use in California is for irrigation and other outdoor uses. In some areas it’s even higher, up to seventy percent of household water use is for urban outdoor uses. Far less is used for landscape irrigation in Australia, so there’s some room for improvement there.

Let’s look indoors, just for a moment. Looking at indoor water use, when we look at Australia, we see that more than 86 percent of households have dual flush toilets, which are among the most efficient toilets on the market. If we look at California, it’s only about 15 percent of households that have even high efficiency toilets, which are slightly less efficient than duel flush toilets, but certainly better than most of the older toilets on the market. Looking also at front-loading clothes washers, again an area where we’ve seen tremendous progress in Australia, with nearly a third of Australian households with front-loading clothes washers, compared with only about 20% in California. In addition, rain water tanks, and grey water systems are far more common in Australia than in California, and these are areas, again, opportunities for not only reducing demand on the efficiency side, but for increasing supply as well – local supply in particular.

Finally, I want to really briefly on Australia’s experience with sea water desalination. It’s a topic of great interest in coastal communities in California. During the millennium drought, Australia spent $10 billion to build six large sea water desalination plants. Of these, only two are currently in operation. The other four plants have been shut down because there were cheaper alternatives available. California has had a similar experience during the ’87-’92 drought when Santa Barbara and some of the surrounding communities built a desalination plant that was never used and remains moth-balled. These serve as cautionary tales and highlight the need to pursue cheaper alternatives including efficiency, reuse and storm water capture first.

With that, let me turn it over to Bob Wilkinson.

Bob Wilkinson: Thank you, Heather. There are so many places we can go with this. It’s interesting to listen in on the short chapter on the call to get a sense of the interest of the participants on everything from pricing to water law, ground water, and desalination.

I got into this, I guess about 30 years ago. I came out of the energy long before that, and then came back to energy, water, climate lengths in the last couple of decades. I started working in Australia over a decade ago, before the drought, with Sydney Water, advising on their long term planning. I was tremendously impressed. I’ll start with that.

Australia’s got lessons that predate the drought. In some ways, I think it’s important for us to look at good water management lessons drought or no drought, or flood. Australia’s been through all of it here in the last decade. They were already, over a decade ago, linking water supply, waste water management and water recycling, rain water and storm water — in Australia they consider storm water as water that hits the ground and rain water is what comes off the roofs – that’s a distinction that exists in the Australian lexicon. There’s a very impressive integration of those water sources. I say we’re doing some similar work here in California, where the California state water plan comes out about every five years, integrating strategies across the board and very much learning from some of the lessons.

I happened to be down in Australia advising on the long term planning for the state of Victoria, just when the rains came in the beginning of 2011. There were people in Australia who were actually saying “Gee, it’s never going to rain again.” Of course, we all know it’s going to rain again, and the same is true here in California. I happened to be there the week that the rains came, it flooded and really began to force a re-think on all the strategies, including the ocean desalination plan that Heather was just talking about. Looking down at what Australia is doing with its water management strategies, currently, with very interesting approaches to mining waste water at different points in major cities to capture and recycle it to beneficial use within the cities. As Heather said, tremendous efforts in improving efficiency in systems, plumbing devices and so forth. Also, rain water harvesting and storm water management practices, with rain water tanks, which of course is historic for Australia in some places, in Tasmania for example. This is just a way of life, people capture rain water and that’s the major source, and in some cases, the only source of water supply. There’s been a resurgence of rain water harvesting, and a lot of lessons to be learned about how this can be done, how not to do it, and how to manage it over the long term. Tremendous potential.

Some of the numbers we’ve developed here for California indicate that, very conservatively, we’re looking at hundreds of thousands of acre feet per year just in the urban areas California, the San Francisco Bay area and urban southern California, all over 400,000 acre feet a year. That is the most conservative calculation, so it’s probably going to be about twice that, and with that comes tremendous energy savings and also greenhouse gas emission reductions. That’s one area where we’re beginning to integrate multiple areas beyond water in California.

A couple of quick points on where we are in California: basically, every major water supply system in California is currently over-allocated. Every major system – that’s the Colorado River system, the North Coast River, ground water in California – so we have challenges. But the interesting thing is that we actually hit a peak. It may or may not stick – but we hit a peak between 1980 and ’95 in total water use in agriculture and in urban, which has pretty much leveled off, in terms of water demand. There are different reasons for that, and it’s interesting to look at and see whether or not cities like Los Angeles that added a million people but is using less water than they were a couple of decades ago – similar for broader urban southern California, much broader water district service area, similar trend in the San Francisco Bay area. And then if you look at nation-wide, you’ll see that we peaked somewhere in the 1980s, and we’ve been pretty level since then in terms of water use in all sectors. There is a sense that good water management across the board and a shift to a lot more local water supply options – decentralized water supply options, which is what many water agencies are going now: recycling, rain water harvesting, efficiency strategies, and increasing reliance on those options rather than alternatives including inter-basin transfer systems.

I’ll finish with one final point here, with the economics of this. Here in California we’ve quadrupled the gross domestic product per unit of water used over about the last 35-40 years, but we did a lot of that in a couple of decades, and then between 1995 and 2005 we did it again, in just one decade, and the trend continues. What that means is that we’re learning in all sectors, how to use less water but use it more productively. It’s important to recognize that there are opportunities in this in terms of economic strategies that actually advance than decline, even in the normal context of the limited water supply. I think I’ll stop there, and pass it along.

J. Carl Ganter: This is Carl Ganter, here. You’re listening to a MaestroConference call hosted by Circle of Blue. You’ve just hear Bob Wilkinson. Next up will be Brian Richter, followed by Mike Young. Just a quick reminder for our listeners, those tuning in: you can ask questions. We’re curating the questions, and we’ll put them forward. The email address is index@circleofblue.org. Or you can tweet them: @circleofblue, #cpx, which stands for Choke Point Index.

Later in our broadcast, here, we’ll drive you to, and you can pull it up now, a Google doc. Take notes there, and we’ll be doing breakout groups. That Google doc is bit.ly/bluecalifornia. We’ll give that address again shortly. bit.ly/bluecalifornia. Now, Brian Richter. Brian, take it away.

Brian Richter: Thanks, Carl. There are some really good points being made here, so let me try to echo or add some on to what some folks have already said. Over the past couple of years, I’ve had the opportunity to spend some time in the Murray-Darling Basin down in southeastern Australia. I was gathering some information stories for my new book, Chasing Water, that’s going to be published in June by Ireland Press. In the book I summarize a number of the lessons learned from that decade-long Millennium drought that took place in Australia, recently. I think some of those lesson should be of interest not just to California, but to anyone who is struggling with water shortages anywhere in the world. Let me just highlight a couple of those lessons here.

First and foremost, and this is likely going to sound ridiculously obvious to many listeners, we have to stop using our water resources – I’m speaking specifically of our rivers and aquifers and lakes – so heavily that they’re running out of water. This means that we need to be able to actively manage our water resources within the limits of their sustainable use. Too often we’re getting tangled up in the weeds of the water crisis, trying to figure out whose water rights are better than someone else’s or pointing fingers at each other about so-and-so’s wasting water here and there.

I think sometimes it’s really important to stand back and take a comprehensive view of how much total use each of our water resources can sustain. In my book I use the simple metaphor of the bank account to explain how people run out of water. The bottom line is that you can’t spend more than is being deposited in the account, or you get into trouble really quickly. It really doesn’t have to be any more complicated than that. We have to stop overspending the rain, in this case. When we over use a water source, of course, we eventually end up in a water crisis, and everybody gets hurt. The farmers, the fish, the city dwellers, entire economies, global food supplies, national security. We just really have to stop doing this to ourselves. The question is how do we do this better?

Here I’ll take a couple of lessons directly from how the Aussies have been handling their crisis, and focus on two key principles that I think are really foundational, really basic stuff that we all need to start paying a lot more attention to. One is that we need to put ourselves on a strict budget, so we don’t overspend our available water. What that means is that we need to spend limits on the maximum allowable volume of water to be taken from any given water source. In the Murray-Darling Basin they called this limit the cap. That cap or limit on water use should be set at a level that allows enough water to be left in the river, or the lake, or the aquifer, to support its ecological health. It should also provide a buffer or a reserve of water that can be used only when absolutely needed, such as in the drought that California’s experiencing, or during the Millennium drought that Australia when through. Note here, too, that this reserve of water can serve as a hedge against future climate change. I think that as Bob just mentioned, there’s virtually no buffer left in California’s rivers and aquifers presently. It’s no surprise that when a drought arrives, everybody gets into serious trouble.

Of course, the flipside of that is you’re going to ask what are you going to do when you‘ve hit that sustainable budget limit of your water supply or when you realize that you’re already living beyond a sustainable budget. Of course you’ve got two basic choices here, just like with your bank account. You either have to find some more deposits, meaning more water to import into your water account, or you have to spend less, you have to use less water. To Heather’s point, it’s always far more cheap, far cheaper, and far more environmentally sustainable, to use less water than to go looking for more. It’s really important to understand that we should never invest in infrastructure for importing or for storing or for desalting water until we’ve fairly exhausted all possibilities for water conservation. Heather hit on within cities what we can do. This is where the Aussies are really kicking our butts. She made the point that the Australian cities are using half the water that western US cities are using. There’s some really, really good opportunities there.

I want to close on the much bigger opportunities for cities to work more constructively with farmers. In California, as you all know, as well as in Australia, as well as in most water scarce places in the world, the vast majority of water use is going to irrigated farming. We have to find ways to help farmers – and here’s a fact that I repeat over and over again – if we can figure out some way to pull back, to reduce the consumptive use of water in agriculture by just 15-20% it’s likely that everybody’s going to have enough water for the coming decades. Of course, we have to find new ways to do that that are fair and agreeable to the farmers. They hold the water rights. I’ll mention that in Australia, the commonwealth government stepped in and put more than $10 billion on the table to help make that kind of collaboration work. That money was used to buy water rights from willing sellers, from willing farmers that were willing to give up some of their water use, or to help the farmers to reduce the consumptive use of water on our farms. Australia also really improved their rules for their water markets, for how water trading could occur. That proved to be immensely helpful for those that valued the water more highly or could put it to a more productive economic use from those that were willing to share, that were willing to give some of their water up with compensation. I think that each of these lessons are really applicable here, and I’ll be happy to elaborate if I have a chance. I’ll stop there, and hand it off to somebody who knows a lot more about Australian water, Mike Young.

Mike Young: Thanks, Brian. It’s great to be here. I’ll start at the top. The first big lesson that Australia learned the hard way is when it gets dryer; it suddenly gets very, very dry very, very quickly. The bottom bit of water in dams and in rivers isn’t accessible, it’s a fixed cost. So it’s packed onto the amount you have to use. It’s very savage and very fast. The biggest experience that Australia had as it wrestled with drought was to decide that its entire water allocation system had evolved in the previous century, in fact over a hundred years ago, and was totally inappropriate for managing the crisis we were having and where Australia was going to have. Australia decided to embrace water reform and to replace its water rights system with one that designed for a future built on sharing, built on being able to trade water across state borders within two days, keep courts out of the systems so that we had a really robust system that was clear – I heard people talking about this in the break out rooms, about the importance of clarity.

The scientists made themselves available and clarified so many issues that were really important, that’s enabled things to happen. The most striking thing is because we put all those arrangements in place when thousands and thousands of irrigators were reduced to having a zero allocation, they were told they couldn’t use any water at all, markets took over, and the impact on the economy was very, very small – we only lost 20% of the value of production through all of this in agriculture because of how nimble the new systems we were putting in place were. Dealing with drought is really awful, but the big message is that transformation reforms work and I’m lucky now having been involved in designing the framework that Australia now has in place, to be over at Harvard working on how to take that to the rest of the world, being prepared to transform policy, to bring in clear mechanisms, that as Brian has said, account properly. Every farmer now has a bank-like water account. They can see how much they’ve got just by logging in just like all of us have online bank accounts now.

Water entitlements are defined as shares, every Australian understands you can only have a share. We’ve removed the over allocation problems. The list of reforms goes on and on. We’ve engaged local communities more and the whole process is one which is excited if you get it right. Drought is scary. It’s really driven us to understand how important water is. When I look at California, and perhaps this is a good question to ask, the really fundamental question is ‘Is California ready now to manage drought?’ Have we got confidence in it? If you pressed 1, you’d think it was really confident. If you pressed 5, you’d think it’s got a major problem. When I look at it, I look at what’s happening at the moment, that too much is in the courts, the plans are not clear, there’s massive uncertainty and nobody really knows where things are going. The great thing that stood out in Australia’s experience in the Millennium Drought was that we have a system in place – the DNA would allow us to manage it well — engage with rural and urban people together, everybody was looking for a solution. Back to you, Brian or to Carl, I think.

J. Carl Ganter: Thanks so much, Mike. That was terrific. Why don’t you ask your question again, we’ll give people a second to digest that, and to vote with their phone.

Mike Young: Can we ask you all to press 1 if you think that California is really well placed to manage the drought as it goes forward and if it continues for another 5 years, and press 5 or anything in between, depending on how much concern, if you think that it’s totally unprepared and has a totally inappropriate system, press 5.

J. Carl Ganter: Thank you so much, Mike. We’re waiting for those poll results to come in. Meanwhile, let me remind you that we’re taking questions at index@circleofblue.org or via Twitter: @circleofblue. The Twitter hashtag for the call is #CPX for Choke Point Index. A couple of quick questions, well none of them are quick because they don’t seem to have easy answers.

One we get from Mark Rivers who asks about water pricing. He writes, “We thought that water price would quickly go very high, so we were a bit surprised at the low interest, but now realize that the farmers have now adapted to their lower water allocations, and no longer need the water they used to waste!” It’s an interesting link between science, policy and sociology as always. I think that Mark is referring to Australia. Mike, I think you’ve touched on this before. You want to respond to Mark?

Mike Young: Yeah, very much so. Firstly, there’s important distinction between price and charge. We’re very careful to talk about the charges that people to supply water and pay and people to take the pay, and price is what happens in terms of signals. When there’s massive scarcity, prices jump up very quickly, and then people start innovating. The thing that stands out, as Mark has observed, prices are coming down quickly. One of the things we also found was that many people found out much cheaper solutions than using water. Our dairy farmers, for example, during the drought, noticed that there was a lot of shriveled grain around. So rather than trying to use water to grow alfalfa to feed to cows, they bought shriveled grain, and stopped using water, and that meant the price of water went back down. So, price drives solutions that send clear signals. If you can have very fast adaptation, then people start innovating. Mark’s right, prices send clear signals, but they also drive innovation and find smart solutions. That’s why the impact on the economy of Australia from the last drought, even though it was a decade long, was quite small, much smaller than anybody ever imagined it was going to be.

J. Carl Ganter: Great, thanks Mike. I imagine that Brian Richter would like to jump in on that, too. Brian, have some thoughts on that?

Brian Richter: Yes, thanks Carl. Thanks, Mark for a great question. Just to add a little bit to what Mike said. I’ll very briefly tell you the story of San Antonio, Texas and the Edwards Aquifer. Back in the late 1990s, because of the overuse of the aquifer and placing a number endangered species in jeopardy, there was a court case, a federal district court case in Texas that basically mandated the state to start managing the Edwards Aquifer more tightly. So they put a cap on the total volume of water use, a point made earlier. They clarified everybody’s share, or rights to the amount of water they were entitled to use out of the Edwards aquifer. Not surprisingly, very quickly, the price of water rose very, very fast. It went to about 5 or 6 times over the course of just a few years’ time. The primary buyer was the city of San Antonio. They really needed more water, they needed more certainty in their water supply, and the primary sellers were irrigators, were farmers. I think, to Mike’s point, about how price can drive some innovative solutions, one of the things that happened is that the farmers were entitled to sell off half of their water rights if they could invest in irrigation efficiencies that reduced their consumptive use. By saving water, they freed up a portion of their water rights holdings, and then they could sell it, in this case, usually to the city of San Antonio.

The one last point I’ll say about that is that until pretty recently, I was actually a pretty big skeptic of water markets. I had a lot of concerns about them. They can really cause some unintended consequences. But when they’re managed properly, and when a lot of the friction that Mike was alluding to that greatly affects and impedes trades are removed from the market, you can see the price adjust to what the willingness to pay is, and there does not necessarily have to be winners and losers in that. There can be winners and winners. In other words, the willing sellers can make enough from their opportunity, and the buyers can get the water that they need.

Mike Young: I’m going to just add in on that, if I can, very quickly. We’ve found in retrospect, it’s better for the environment, it’s better for business and it’s better for communities. It’s really a big change that’s occurred.

J. Carl Ganter: Thanks so much, Mike and Brian. We have some more questions here. Let me take a look here.

Brian Burt: Hey Carl, I just thought I’d share the results of Mike’s question. It looks like most people think that California is not very well prepared. There were only a handful of people who rated it a 1 or a 2. The vast majority had us down us down at 4 or 5, and there a few 3s as well. About 20 percent of those responded with a 3. The vast majority feeling like California’s currently not on a trajectory to tackle some of these solutions that the panelists have been discussing, like water markets. We’ve got our work cut out for us here.

Mike Young: I’d like to follow in on that. Something which I think is really important. That’s how long it takes to even build infrastructure. I’m a bit alarmed when I see all of the promises around to put in new pipes, put in new systems, hard engineering solutions. We learned the hard way in Australia, to change infrastructure is ten-fifteen year process. It’s slow; you cannot just magically re-plumb a state. In the short term the only thing you can use to deal with drought is policy. It’s a very hard lesson to learn, but you cannot build dams, you cannot build pipes, and you cannot make water available very quickly by changing the way you plumb your system. That’s a very slow process, and it takes time. If California’s worried about water, then I think it has to do one thing, it has to embrace the fact that it needs to transform its entire allocation system, as we did, and its entire management system, and put in one that robust and Australian water managers all talk about robust institutional arrangements that you can trust, robust institutional arrangements that you can bank on with confidence, and which don’t end up in the courts, because courts take two or three years to resolve issued. Water systems take months to dry out. You cannot go one with the system you have if you want to stay out of trouble.

Heather Cooley: If I could just jump in here? I do want to note that many of the efficiency opportunities out there are things that can be captured very quickly, especially if we move towards doing some of the direct install programs, we’ve seen examples of this in Los Angeles, back in the early ‘90s, also New York has done some work on this. There are opportunities to go in, to really quickly retrofit communities in a way that saves water, it does generate jobs, it can even, as Bob was mentioning, save energy. There are a lot of opportunities where we can quickly go in and make some major reductions in how water is used.

Mike Young: I would agree with that. It’s all everywhere. There are more opportunities in things like replacing toilets, putting in low volume shower heads, changing the way you manage water and irrigation systems. That’s all done easily. But when you start talking about building new dams, building major pipes and huge engineering solutions, that takes a lot longer. A de-sal plant, that we talked about, everybody said we have to build them, by the time they were ready to be operational, the problem was gone. We’d solved it without needed what we’re spending all our money on. A very expensive lesson that’s cost Australia billions of dollars we didn’t need to spend.

Brian Richter: Just wanted to, to Heather’s point, about how quickly you can save some water. The Australia case, during their droughts, within a just a handful of years’ time, 3-5 years, a lot of the Australian cities were able to cut their water use by 35-50%. Heather mentioned that there’s such disparity between how much water western US cities are using as compared to Australian cities to begin with. Even in Australia, they were able to really substantially reduce in a hurry. It’s a really important lesson learned.

Mike Young: That happened because people became water literate. A lot of investment was put into educating people about how important water is and making sure that little bit that was there made as big a contribution to the economy as it possibly could.

J. Carl Ganter: Great. Water literacy is certainly one of the big topics in a lot of the questions here. One of the questions is from Madeleine Carry. She asks: “Is changing the structure of federal and state water management a strategic move that could better prepare us to handle future choke points? Is it worth it?” This moves us more into the policy conversation. Who’d like to jump in on that?

Mike Young: Why don’t I just very quickly just say what Australia did? Australia embraced the idea of having tiered levels of government structure and really reforming that. At the very top, after very heated debates between federal politicians and state politicians, it was ultimately decided that the entire Murray-Darling Basin should be managed by an independent authority of 5 people, all chosen for their expertise. In Australia, we have a thing which is like your federal reserve, which is called a reserve bank, and people said we need an expertise based government structure that makes the hard decisions, puts the limits in place everywhere, and that will bring confidence to the system. I can assure you now that we have that new framework in place; we have the confidence we know that working with great elegance and simplicity because we’ve taken the politics out of water management on a day-to-day basis.

Brian Richter: Carl, your question presents a good opportunity to talk about some things that Australia got wrong. Sorry, Mike, I hope I get this story right. Mike mentions that during the drought in particular, the water management policy setting very much moved to a centralized fashion. The commonwealth government essentially seized control because it didn’t feel that the states were moving quickly enough to stave off catastrophe. I talk about that experience a little bit, and I think a lot of you heard about the hostilities, the reactions through some of the eventual basis plan that came out in the Murray-Darling. I think the point I want to make here is that one of the lessons that I’ve learned over the last couple of decades looking at water crises, and these debates and arguments all over the world, is that it’s really important to provide as much access as possible to the most local level that is feasible. In other words, bring some of the decision making, bring at least some of the planning and some of the discussion, and some of the dialogue into the local communities. Those local communities know what they can and what they cannot do. They know what they’re willing to tolerate and what they’re not willing to tolerate. What we’re seeing in the places that have provided that kind of stakeholder local community engagement, is that they’re ending up with more durable, more robust, more sensible and in many cases, much more cost effective plans. Figuring out how you can have a central oversight that then enables that sort of local planning and dialogue to take place and inform the resulting decisions and plans is very important part of this policy.

Mike Young: A classic example of that, Brian, which is a very important lesson I think for California, is we used to have a rule in place that said you had to use your water, sell it to somebody else, or else you’d lose it. As a result of that, we discovered that too much water was being used, and we changed the policy around where farmers were allowed to leave water in dams, and eventually save it. We went away from all the rules about beneficial use and said “look, if you want to leave it in a dam, and keep it for next year, you can do that.” We brought in that rule, and the day we did it, the price of water in the marketplace doubled, because every farmer knew they were using too much water, but they were using it, because if they didn’t use it, they would lose it. What they’ve wanted to do was to save it for next year. We didn’t let them do that. When we did let them do that, they save a lot of water, much more than people expected to it. Involving local people in dam management was one of the big things we learned we had to do. The people at the top, the state administrators, got it seriously wrong, and the result of that was the drought was much worse than it needed to be. In fact, it cost us million, cost communities millions, because the bottom up solutions weren’t allowed to operate.

J. Carl Ganter: Thanks so much, Mike. Quick reminder, if you’re using the Maestro dashboard, refresh your page, and you’ll see updates, maybe some feedback from us on your specific questions, and also coming up in a bit, we’ll ask you to go to a Google doc, and the address for that is bit.ly/bluecalifornia. We have a question here from Vince Hancock. It dovetails perfectly into what Mike was just talking about related to the grassroots level. This is a question for all the participants. “How much would you say people in your own immediate communities – the participants’ and we’ll probably toss this out in the discussion groups later – how much do they understand the importance of water issues? How engaged are they? Do they understand that there’s a policy issue? Do they understand that there’s a use issue? Heather, you’ve been following this pretty closely and monitoring how people understand and respond to the issue in California. Maybe you want to kick us off?

Heather Cooley: I do think there is a growing awareness about the issue. We are very focused on the drought right now. I think it’s important to note that we have some long-standing and intensifying water challenges in California that we need to address. In average years we have problems; people aren’t as aware of them, so the drought does certainly provide an opportunity for us to really focus in on and begin to understand and value water, and realize its connection to our environment, to our society, to our economy. Historically, when we’ve thought about and looked at these types of issues, we’ve thought of it as a water supply problem, that we really need more supply, we need to build bigger dams, and we need to look at new – perhaps look out into the ocean at sea water desalination. Bob really spoke to this, there is growing recognition of the need to develop more robust local supply, to look at all of the ways in which we are wasting water in our homes, in our businesses, how we’re wasting storm water, it’s flowing off and causing pollution issues, when we could really be capturing that water and using it to recharge ground water. The tone now is different than it has been in the past. There’s a lot more focus looking at opportunities to reduce demand, and to looking at opportunities to reduce waste more broadly. I think that it’s a good thing, obviously. There is more that can be done. We need to have more of those discussions. We’re at the beginning of this.

J. Carl Ganter: Heather, to follow up on that, too. There’s a timeline ahead in California. Maybe you can give us an idea of a few of the key calendar events that are coming up that we want to watch out for throughout the summer, as far as measurements, as far as river flows, things like that.

Heather Cooley: Certainly, the next snow survey will be important. Snow surveys typically come around the first of the month. The April snow survey will be critical. There will also be updates on allocations from both the state water project and from the federal water project as well. We’ll have a better indication of how much water will actually be available. Another thing to be looking out for: farmers are making decisions now about what to plant and where to plant it. We don’t have a sense of who will be fallowing and what will be fallowed, but as summer progresses and as spring progresses, we will have a better sense of that. We’ll need to be looking at issues around energy. California is dependent on hydropower. Hydropower generally provides about 15-20% of the state’s electricity – again, depending on the year, depending on the flows. Because we have a drought, there is less water to run through the turbines, therefore less energy available from that source. We will need to be looking towards the end, especially around August, when we tend to see spikes in energy use, at energy prices during that period, and where we will be getting our energy sources because hydro won’t be available.

J. Carl Ganter: Great. Thanks, Heather. I also want to take a moment, too, and welcome Upmanu Lall to the call. He’s just joined us from Columbia University in New York. Manu is director of the water center there. Welcome. This might be a question for you. Heather was talking about snow fall measurements, things like that. These issues also involve ground water – the quality as well as the volume. Manu, I’d love to hear a little bit more about the role ground water plays, particular in the drought situation, and what are some of the things that we should be aware of, in talking about ground water?

Upmanu Lall: Thanks, a lot, Carl. I’m happy to join. Ground water, the best way to think about it is that in a place where there is a high degree of radiogradity in rain fall and snow fall and surface water supplies, ground water is your buffering storage to drought. In many places, and that include California, historically, you’ve been pulling out more ground water than goes in. You end up with declining water levels. That reduces our ability to buffer, at least economically, because as the water levels go deeper, it costs quite a bit more to pull the water out. That’s sort of the general framing of the issue. The other thing that’s been going on is that normally ground water is usually of very high quality, with the exception of some fluoride or arsenic in it. But with the high intensity of agriculture, especially in the Central Valley, and then in over areas of pollution from other sources, ground water has been getting contaminated. The resident time, or the amount of time that ground water is usually long, which means that it moves slowly, so it’s harder to clean it up. That creates a secondary problem.

Mike Young: A very important lesson from Australia is to be very careful of what you might describe as flow switching. A lot of ground water systems are very closely to connected to a river, and people often think of the river or as a stream as only being a few yards wide, it might be 50 yards wide or whatever it is, they fail to understand that a stream goes out well through the banks and a long way out it become ground water. In the middle of the drought, we discovered quite a few areas which used to be “gaining sections” where ground water would flow into the river, they swapped and they became losing sections. As people turned to ground water, they in fact were pumping water out of the river, and that meant the people that were relying on river flow didn’t get the flow that they had. When people rush to ground water the accounting has to be right. Part of all these processes our Australian administrators learned the hard way that you should never ever make announcements about water that’s going to be available until it is available.

In the early stages of the drought, some of our water administrators made announcements that everybody was going to be entitled to have a certain number of acre feet of water, and then they found that didn’t arrive because of things like connections were being dug to surface water and because expected rain fall didn’t happen. They had to claw back as a result of that now, we only make allocations of water when the water can be seen and is physically there. The other thing we do as part of bringing clarity to all the science that’s emerging and all the measurements are made, allocation announcements and all policy change are only made on the first working day after the first or the fifteenth of the month. People know when to look to see what information is available and all people have a fair opportunity to make informed decisions. We’ve had to work hard a communication, hard at the science, hard at the hydrology, and how to do all the accounting systems.

Keith Schneider: As we move through the discussion, we keep touching, and in some cases, immersing ourselves in policy debate. That’s the toughest part of this. Some of our panelists described that the transactional pieces, the equipment pieces, the practice pieces can be encouraged and advanced as long as the leadership — intellectual, political, local leadership – can see the outcome. Right now, we’re facing in California, as we faced in Texas, a governing structure that’s really not adept at the moment, or as adept as it was in previous eras, at recognizing the risk, embracing a set of targets and then acting on them in a way that’s a reasonable amount of time. The United States, as in other places that we’ve reported from around the world on these very important long-term, complex, ecological responses that are now appearing around the world, the governments are not up to the challenges, or moving as quickly as the unfolding problem. California could be the place that sets some new directions, some new trends in how people decide to manage an urgent and increasing risk. It’s played that role in its previous years in the twentieth century. It would be really interesting and important for California to show us that path so that the entire country could learn from it.

Mike Young: As I understand it, the Californian system that you have in place, the surface water rights was really developed and designed for gold mining back several hundred years ago. It’s interested that all of the very, very senior rights that were issued before 1914 have been protected and no one has been prepared to look at them. In Australia, the people who held those rights, were also very, very protected. When we moved to the new system, it didn’t take long before the people who held the old, very senior rights, saw them jump in value or how much better they were all off. I don’t think there’s a single person in Australia who would want to go back to the old system that we had in place. The new system is one which is much more valuable because markets understand that there are problems in the system. There are risks associated with holding these rights. We’ve removed all the risks and put in place a new robust system. Now everybody would always agree to stay with the new system rather than go back. It was painful and very difficult, as Brian was saying. There were a lot of arguments, a lot of fear, a lot of confusion as we went forward. We all learned to communicate much better. The final outcome is something I thin Australia can be very proud of. It’s a world leading system.

Keith Schneider: It’s really interesting to close this circle between California and Australia. In our reporting, my reporting on Australia, I learned that the very same Canadian-born brothers, who designed the early parts of the California aqueduct and storage and transport system, were brought to Australia at the end of a pretty severe drought that the end of the late 19th century, and helped Australians design the beginning of the Murray-Darling Basin aqueduct, transport and storage system. We can now take back from Australia some lessons of how to deal with drought would be useful in every way.

Mike Young: The history is really an important one to understand. Australia was very lucky that the man who became the nation’s very first prime minister visited America before he took on that role. He came back with one recommendation. He said do not go with a prior right allocation system. It’ll lead to disaster. It just divides communities and stops solutions from emerging. He went back and was adamant with his first big contribution to the nation that became Australia in 1900.

Brian Richter: You’re question was sort of suggestion or you’re alluding to the difficulty of policy change. Just two quick reaction to that, Keith, that we’ve seen from Australia and some other places. 1, I made the point about local community stakeholder engagement. We need to find some way to share the risk of policy reform with the local communities. In other words, put their destiny back in their hands. Give them more decision making power. Have them own the challenge. Have them discuss the best ways to try to resolve the problems. Often times you see some pretty interesting policy shifts or at least shifts in terms of the priorities of how to address the water problem. Texas, when they went to a stakeholder-based planning process back in the late 1990s, water conservation was about 10-14 percent of the overall mix of water strategies being used to being used to balance the water budget in Texas. Now it’s upwards of 25%. It’s because those stakeholders from those local communities are helping to make those decisions, helping to set those plans.

The other point is so well evidenced by Australia. To quote Mary Poppins, a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down. The commonwealth government really stepped up. They realized this is going to be very difficult to move to a different kind of system of managing water, to try to reduce the overall consumptive use. They put $12+ billion on the table to help – that was a lot of sugar to help the medicine go down. It can be very material, very meaningful to people who are going to end up being impacted by any sort of policy shift.

Keith Schneider: My point in this is that – and I said this on the last call that we did a month ago – the earth is pushing back very hard now. As we grow, as human beings, 7 billion of us, as we move our very flimsy transport, communication, transportation systems into places that are more difficult to manage — deserts, the Himalayas, the oceans – we have, as a society, have one gear, which is forward, which is more. More energy intensive, more water intensive, in many places. Our policy mechanism doesn’t reflect the need. The earth is telling us we need to change. I happen to believe that we’re not as a species have a death wish, so we’re being forced to embrace different ways of doing what we do.

The drought in California, the drought in Australia is proving that we have the capacity to adjust. The question is do we have the capacity to adjust at the speed that the change is occurring. What I’ve been finding is that in most places in the world, we don’t. This country, in the 20th century, had the capacity to adjust very quickly to changing conditions and to national goals. This brings to mind Kennedy’s goal to land a man on the moon and bring him back safely within a decade, and we were able to do that. We’ve done that in other kinds of national programs. The kind of program that’s going to be necessary to respond to the long term consequences of a deepening drought in California need to be begged, but they need to be done in a way that has timeliness to it. These are changes that need to occur over the next decade in a dramatic fashion. Do we have a nation or a state have the capacity to do that? My reporting is indicating that there are lots of questions to be asked about that.

Heather Cooley: One of the things, and Brett you mentioned this in in your opening comments, is really around ground water reform, and the need for ground water reform and the opportunities for reform. Ground water is a critical storage – it’s something that we can draw upon in drought. This is perhaps a little bit different in Australia, ground water in California; we have a lot of it. We’ve been over-drafting it for decades, but there is an opportunity to have fundamental reform and how we manage it such that it is a storage that we can rely on to get us through these dry periods. In some areas, we do have the local management of ground water, and that has proven to be effective and successful. In large parts of California we still do not have any real comprehensive ground water management. As a result, that’s led to long term decline; it’s led to a situation where we’re not able to draw upon it now when surface supplies are limited. That’s an area where there is a lot of attention right now.

There are proposals that are being put forth to the governor. There’s a lot of discussion about how we can make reforms in this area. There’s significant opportunity to help us address not only this drought, but future droughts. Frankly future wet periods. When we think about the future of California water, it’s not just about more frequent and intense droughts, it’s about greater variability; it’s about greater extremes. We need to think about how we can holistically address this, to capture water when it’s in flood periods, to use it to recharge ground water so we can then draw upon that reservoir when we need it.

J. Carl Ganter: Bob, you’ve done quite a bit of work in this place. We’re also getting quite a bit of questions about climatic scenarios, populations growth, along a similar lines. How will we respond? Coming back to our poll early on, is California ready for this? Maybe we can talk about just a little bit more about tools to anticipate droughts, and then also how do we turn that into, or does that turn into a national issue and a national strategy?

Bob Wilkinson: A lot of good questions. Some very good are points being made here. Let me just say to start that we talk a lot about California, and there’s sort of a perception of the ‘dry west’ and the drought situation in the west, but it’s important to remember that the southeast, say Atlanta, just went through a pretty wrenching water shortage issue. It may have been more a longage of demand than a shortage of supply. Without meters and with use patterns that didn’t work very well, and the rain stopped for a relatively short space of time compared to the west. The other one’s Florida. You look across North America; the one large scale operation desalination plant so far is in Tampa. It’s had some difficulties. It leaves one to realize that even Florida that is generally perceived as a wet place has its water storage issues. We have issues of water supply. And this mess between supply and demand all over the continent, certainly around the world.

When I look at the federal role and the state role, and current California context of the drought, even if we cycle into an El Niño, and we go wet again, most of these same issues are still going to be here in terms of undervaluing water resources, prices not fully reflecting value including externalities and environmental values. I don’t see a lot of money coming from the federal government in the foreseeable future. The patterns that we set in the past half century with the federal government coming in and helping pay – quite generously – a lot of systems throughout the country and certainly in California. Even the state governments funding a lot of these systems is a process and a funding stream that may have changed fairly fundamentally. The bond that we were talking about has actually gone onto the ballot, come off a couple of times already, at just over $11 billion is questionable. We have a number of different proposed version of this bond that go on to the ballot, and we’re not completely certain it will go on, and if it does it’s not exactly certain which one will go on, nor is it clear that people will vote for it. The pattern of bond finance over the last decade or so is a bit of an aberration. It’s not a long term pattern. One I am seeing as a funding mechanism that is often referred to as rate based financing. That is, people who are paying the rates and/or taxes are actually going to be paying the freight of most of the water infrastructure involvement. That is already the case. There are very good studies of public policy institution of California’s come out with a good study on where do we get the money for water systems and the vast majority is local financing, followed very distantly by the state and federal governments. What that boils down to is that people have to be willing to pay for solutions that they perceive are really going to make a difference.

This goes back to the conversation about the localization of a lot of these issues. We do see a lot of very promising efforts at the local level, cities, water agencies and so on, that are getting a grip on management of ground water, improving efficiency tremendously, doing a lot of storm water capture and recharge. Ground water is about a third of our supply, on average. It goes up during drought. So it’s not just a drought supply. Ground water is a significant part of our water supply process. It’s basically a reservoir, but it’s underground, instead of a surface reservoir. And when it’s well managed it can be an incredible valuable asset, and people get that so I think we’ll see more of that. The trend I’m seeing here in terms of the current drought and the long term is developing the perception of the value of water, and the viability of a lot of these local solutions that are good at providing much more than people realize, when you add it up to the total system.

Mike Young: One of the things that Australia did, and there’s lovely words in what you said there, you mentioned local approaches, we’ve developed a whole dialogue around what’s called localism. It’s been facilitated by really clear guidance from the top, and there’s a thought experiment I can imagine. The 13 western governors of the United States getting together and announcing a big and western water initiative, with a clear framework that provides guidance. That’s what Australia did. They put together what was called a national water initiative and said that all water entitlements were going to be converted to shares, it was going to be a whole pile of things. The environment was going to be given some senior rights, because when the environment was there right from the start, so if we just issued some rights that were as senior as the other rights, and gave an irrigation company’s rights to some of the losses, and bought everything so the externalities became internalities; they just became part of the new framework, so that local people could develop local solutions with confidence. We saw in places like Kimberley, where the debt irrigation company, New Griffiths, was handed rights, and they sat down with the company Rubicon and they worked very carefully to develop what is now world-leading, total channel control systems. There are local solutions that emerge from putting together a robust, carefully thought through national water initiative that empowered everybody to find local, fine-tuned solutions, and to bank the savings they made from that. It created a lot of wealth, and that wealth paid for the solutions. You didn’t need huge grants for most of the innovations that occurred. They occurred because local people were allowed to find local solutions, and people weren’t allowed to stand in the way and debate solutions. People who had a local solution were allowed to implement them.

Brett Walton: I’ll just add two quick points about local solutions and the state-wide plan. The one that was ground water reform and governor wants to have the two-prong approach, so preference #1 is for locals to manage their ground water supplies on their own. Prong #2, if locals aren’t willing to or able to do that, the state will step in. So the conversation that they are having right now in California, are trying to define those boundaries, to define what is a well-managed ground water basin, define when the state should step in, define when the state should step out. The governor has instituted the public comment process that’s on going. There’s about a month left, and there some responsive dialogue that’s going on around the state right now to define what local control and good local control is.