Study: Water Stress Affects Fewer Cities Than Previously Thought

Pipelines and canals buy some cities a ticket out of water stress — for now.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

For water, as for the rest of life, money is the great insulator.

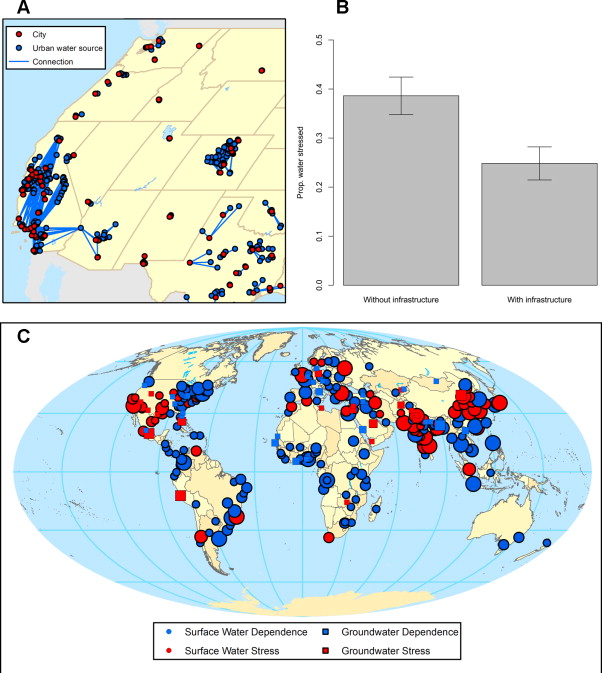

A new study on urban water stress reveals that fewer of the world’s large cities than previously thought are approaching severe limits on their drinking water resources – just 25 percent of cities with a population greater than 750,000, not 40 percent as had been claimed.

Why the lower number? Because the expensive canals and pipelines that draw water from distant basins were not accounted for in earlier assessments, which assumed, for example, that the only water Los Angeles was using came from the local rivers and aquifers west of the San Gabriel Mountains.

Massive water diversions allow cities to flourish in areas in which current lifestyles would otherwise be impossible. Los Angeles, in fact, pulls more water from outside its natural watershed than any city in the world, according to the study, which was published online this week in the journal Global Environmental Change.

A wealthy city benefiting from investments fought over and built more than a century ago has that advantage. Many poorer urban areas today do not, said Rob McDonald, senior scientist at the Nature Conservancy and the study’s lead author.

“Poorer cities often can’t build themselves out of scarcity,” McDonald told Circle of Blue. “And it’s going to be harder for them going forward. The fastest growing cities are the poorest and they may need to double or triple their water supply but don’t have the capital to build a large water transfer project.”

In such cases the power of international lenders could be called on, said McDonald, who cited Sana, the perilously dry capital of Yemen, as an example where outside money would help.

Even if money is not a problem, geography might be. Most cities in the study have an unstressed water source close by. Roughly 80 percent of cities could find a source to supply 1 billion liters per day, enough for several million people, within 22 kilometers, according to the analysis.

But 10 percent of cities would need to build a canal at least 48 kilometers to access such a source. Most of these geographically limited cities are in poor or developing countries, notably China, Mexico, and in Central Asia.

Zooming in on the Problem

The ability to assess water supply challenges at this level of detail was possible because of a groundbreaking data set the research team assembled. Researchers pieced together the individual rivers and aquifers that supply more than 500 cities worldwide and identified, as best as possible, the location at which water was drawn.

Cities use a mix of water sources. The researchers tallied both rivers and aquifers, and used hydrological models to define when each source reaches a point of stress. For rivers, this is when more than 40 percent of the available water at any given point in the watershed is withdrawn by farmers, industries, power plants, or cities. For aquifers, water stress occurred when the water pumped out of the ground exceeded the amount soaking back in. (For a complete list of the 264 cities used in the study and their stress status, go here.)

Environmental flows, or what is needed to maintain a healthy aquatic ecosystem, were not taken into account. If they were, less water would be available for humans and more cities would be classified as stressed, bumping up the total to perhaps 29 percent of cities, according to the study.

A city judged to be water stressed, however, is not necessarily a city in immediate crisis. Stressed means that cities face certain challenges, some that are chronic and others that are acute, McDonald explained.

“Water stress means a city is more vulnerable to drought,” McDonald said. “It means that there is more potential for conflict, not violent conflict but disagreements between states or other cities or countries over water.”

A city, for instance, that withdraws water from its aquifer at an unsustainable rate might see its energy costs increase in the short term as water is pumped from deeper depths. But such pumping could go on for years before a noticeable dip in the water supply if the amount of water stored underground is large enough.

Setting the Stage for Future Research

The fresh look at water stress is the first in a series of research projects that will use the City Water Map database to assess urban water supply challenges, McDonald said.

One study will use the latest climate models to map how changes in river flows brought by global warming will influence urban water stress. Another study will consider how upstream changes in farming or forestry will affect water quality and alter the cost of water treatment. A third will examine the relationship between cities and agriculture and pinpoint where shifts in farm practices might free up more water for urban use.

The latter study, on agriculture-urban partnerships, is especially important. Even if some cities can afford large canals, transfers from agriculture would be cheaper, use less energy, and keep river ecosystems intact.

And even though big infrastructure projects help, they are not a cure-all. System expansions eventually reach the limits of geography, cost, and conflict. After all, Los Angeles, for all its canals, is still classified as water stressed.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

How come Sao Paolo that is facing an unprecedented crisis is not even mentioned or reflected in the chart? An oversite

Binayak, as with many studies it’s important to note what variables are measured. In this case, the researchers defined water stress for surface water as withdrawing more than 40 percent of average supply. For groundwater, they defined stress as withdrawing more water than soaks back into the aquifer.

According to these metrics, Sao Paulo was not determined to be in water stress under normal conditions. The drought, of course, has drastically cut rainfall while authorities have been largely unwilling to reign in demand. Leaky water pipes are also a problem — much of the supply is lost between reservoir and faucet.