Waukesha Presses First Test of Great Lakes Water Compact

Drinking water diversion proposed for out of basin city.

By Kaye LaFond

Circle of Blue

WAUKESHA, WI — There was a time in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when this southeast Wisconsin town was known throughout the Great Lakes Basin for its ample supplies of pure water. The aquifers underlying the forests and meadows served up water of such taste and compelling clarity that local spas marketed the health restoring qualities to city dwellers in nearby Milwaukee and Chicago.

A century later Waukesha is a much bigger city and its water supplies are again attracting considerable attention from its Great Lakes neighbors.

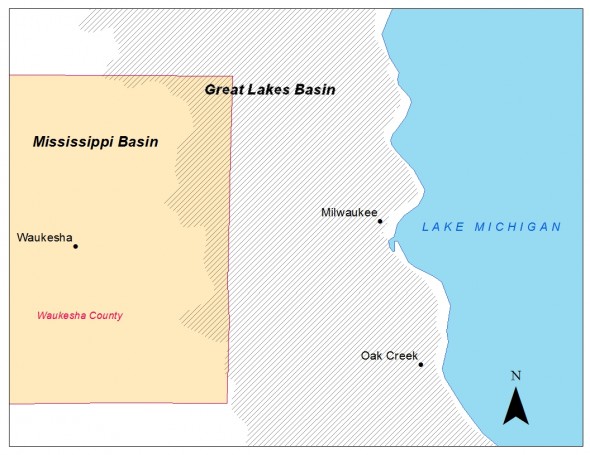

After decades of suburban and industrial growth Waukesha’s deep groundwater aquifers are contaminated and becoming exhausted. Almost a year ago, in October 2013, the city of nearly 71,000 residents formally proposed to fix its groundwater water supply problem by tapping surface water from Lake Michigan provided by the water treatment plant in Oak Creek, another Milwaukee suburb, 31 miles to the east.

The amount of water that Waukesha is ready to buy and have transported in a pipeline is 10.1 million gallons a day, or 1 millionth of 1 percent of the total supply of water in the Great Lakes, according to city figures. But that seemingly trivial withdrawal has stirred a legal, environmental, and potential diplomatic tempest in the Great Lakes Basin. The reason: In seeking water from Lake Michigan, Waukesha’s proposal has become the first formal test of the water diversion rules under the 2008 Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact.

The agreement involving eight states, two Canadian provinces, and two federal governments banned diversions of water outside of the Great Lakes watershed. But the compact included an exception for cities within counties that straddled the watershed boundary. One of those cities is Waukesha, which lies within the Mississippi River Basin; about 1.5 miles west of the Great Lakes watershed divide.

Dan Duchniak, the general manager of the Waukesha Water Utility, is well aware of the precedent his city may be setting. But Waukesha’s options, he asserts, are limited. “If the application for Great Lakes water would be rejected in full or in part,” Duchniak says, “the city would need to move to one of its alternatives, which would be a combination of two of three sources described in our application: shallow wells; deep wells; or river bank inducement [wells along the Fox River].”

Dave Dempsey, a long-time environmental advocate and the award-winning author of “Great Lakes for Sale,” argues that Waukesha’s application doesn’t meet the requirements for exceptions provided in the Great Lakes Compact. The amount of water Waukesha seeks is 45 percent more than it uses now and is designed to allow the city’s sprawling growth pattern to expand.

“Waukesha’s proposal goes beyond what is needed to address legitimate public health concerns,” Dempsey says. “If approved, it will set an unfortunate precedent for implementation of the compact. Great Lakes diversions for urban sprawl could open the door for other diversion demands that could threaten the unity of the Great Lakes states.”

“If Waukesha is not required to downscale its proposal,” Dempsey adds, “the decision will signal that the region’s decision makers are not as serious as they need to be in conserving Great Lakes water.”

A Historic Water Agreement At Center of Continent

The Great Lakes Compact, signed by President George W. Bush in 2008, is intended to protect the Great Lakes from what its authors called “overspending.” The agreement came in response to several proposals at the turn of the 21st century from international companies to ship Great Lakes water out of the basin in tankers and in bottles.

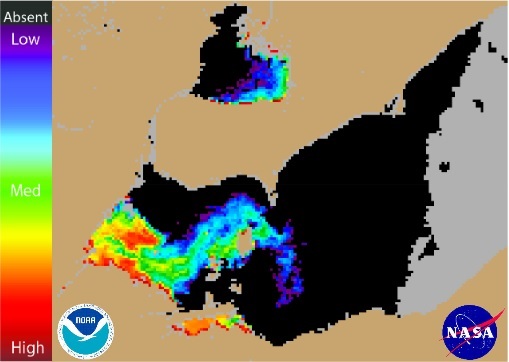

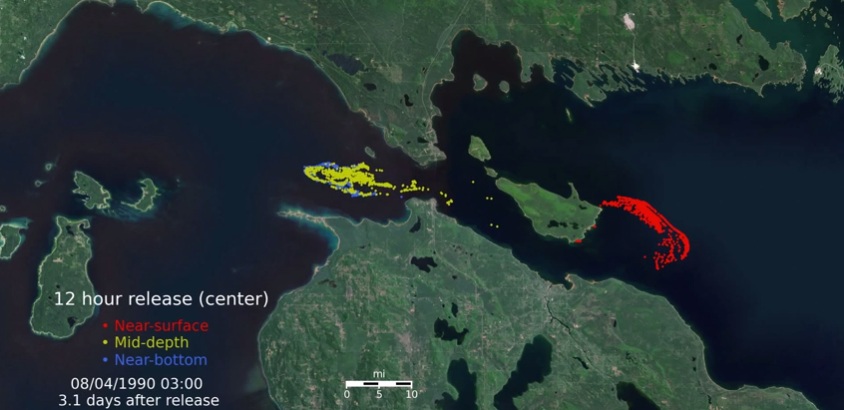

Under the compact, the eight Great Lakes states and two Canadian provinces agreed to adopt water conservation plans and to abide by strict rules for allowing and managing diversions of Great Lakes water. The compact recognizes the lakes as a shared resource, which no single state owns, but of which all states are stewards. A defining feature of the compact is its emphasis on using regional cooperation to manage the lakes as a single ecosystem.

The agreement’s primary provisions are aimed at minimizing the amount of Great Lakes water that is unnaturally diverted out of the Great Lakes basin, never to return to the lakes. There are limited exceptions for communities, like Waukesha, that straddle the basin boundary and may be allowed to divert water for public use if they 1) return unconsumed water to the basin after use, 2) show that the need for the diversion cannot be avoided through conservation and efficient use of existing water supplies, and 3) show that the diversion will not hurt water quality or quantity. Such diversions require the approval of all eight Great Lakes governors.

Case For Diversion

Waukesha is busy making its case for such a diversion. The city’s water supply relies mainly on wells which draw from aquifers deep underground. Over the past century, the level of the deep aquifer water table has dropped by about 500 feet and continues to drop at a rate of 5 feet to 9 feet annually.

Not only has the groundwater been depleted, it has become more and more affected by pollutants like salt and radium, which have dramatically increased in concentration. The city is under legal obligation to fall into compliance with federal radium standards by the year 2018.

None of the city’s alternative water supplies are exactly ideal. While the use of shallow surface aquifers has been discussed, there are 4,000 acres of wetlands near the proposed shallow drilling area that may be harmed. Drawing from the Fox River also poses environmental issues. The method involves sucking water through the soil just adjacent to the river.

The city asserts that its best option is to purchase an annual average of 10.1 million gallons per day from Oak Creek, which lies within the Great Lakes basin and ultimately obtains its supply from Lake Michigan. That is 3.15 million gallons per day more than it currently uses.

In the documents justifying the diversion the city asserts that its population will grow to 97,400 by 2050, and it also needs to make provisions for supplying water to new industries. But water use by industrial companies, which reached 4.1 million gallons per day in 1980, has dropped to 900,000 gallons daily, a nearly 80 percent reduction, according to city reports.

Waukesha residents support the city’s application, which is being reviewed by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. “Our new mayor was elected on a platform that included obtaining Great Lakes water for the water supply. He won receiving 62 percent of the vote,” says Duchniak. “Opposition to the water sale has primarily come from outside of the City.”

Jim Olson, a lawyer specializing in water law and founder of FLOW, a Great Lakes law and policy center in Traverse City, MI, is among the critics. “The reason for the exception for straddling communities was to meet their fundamental needs, not as an artifice to expand and grow other communities outside the basin,” Olson says. “The Great Lakes by Supreme Court law are held by the states, and under the compact, as a public trust for public trust purposes like boating, swimming, navigation, fishing and health or sustenance of those who live in the basin. This means the water can’t be transferred outside the basin as if it was a commodity for non-public trust purposes.”

Kaye LaFond, a recent graduate of Michigan Tech, is designing graphics and reporting this summer from Circle of Blue’s Traverse City office.

is both a scientist and a journalist, she holds an MS in Environmental Engineering from Michigan Technological University, and she brings proficiency in ESRI’s ArcGIS mapping software.

Although the author was told that the population projection for the city is 76,300, not the 97,400 she claims, no correction has been made to this story. Specifically, the city said:

• The 2050 population projection is incorrectly cited, creating a false impression of aggressive growth. The article cites the City’s current population of about 71,000, but later incorrectly says the City’s population will grow to 97,400 at buildout in 2050. The actual population projections at buildout are 76,300 for the City and 97,400 for the service area. While the population served increases by about 26,000, about 10,000 of this service population resides in the area today and is served by private wells (See Volume 2 of the Application, Water Supply Service Area Plan). The claim that the City is seeking water to allow sprawling growth is not supported by state and regional population projections. It is not supported by approved land use plans through 2035. With an actual projected population growth rate of 0.5% per year, statements like “The amount of water Waukesha seeks . . . is designed to allow the city’s sprawling growth pattern to expand” are not true. If you had asked about this issue, I could have provided you with the facts.

In addition, no mention of other relevant information about growth in our FAQs was provided in your article, including the fact that only 15% of the land in the service area is available for development.

The city’s complete response was:

Regarding your statements about the condition of the deep aquifer, we are not aware of technical studies projecting the deep aquifer is a sustainable long-term water supply for the City or recommending the deep aquifer as a source of supply to minimize environmental impacts.

There is evidence of a recent increase in groundwater levels in the City’s deep wells, which we believe may be attributed to the following factors:

• Water conservation and water use efficiency have resulted in the City using less water.

• Since 2006, the City has been withdrawing as much as 20 percent of its water supply from the shallow aquifer, reducing deep aquifer withdrawal.

• Waukesha’s deep wells have recently been out of service for extended periods to accommodate major repair or maintenance activities. Static groundwater levels rise when wells are not operated.

• Several water utilities in Waukesha County abandoned deep wells or drilled new shallow aquifer wells. Going forward, however, tighter well regulations are likely to make siting of shallow wells more difficult.

• In addition, the recent recession decreased water sales for most utilities, but economic recovery could reverse that.

The near-term localized conditions may not be representative of conditions across the aquifer, may be temporary and may not be sustained for the next 50 years. It is not prudent to assume that water levels in the deep aquifer will become sustainable.

The near-term localized conditions do not change the long-term regional impacts of over-pumping the deep aquifer. These impacts are so severe that state legislation was put in place to better protect and conserve water resources. The Wisconsin Legislature and regional technical experts agree that 150 feet of drawdown is harmful to the environment. With deep aquifer drawdown of 400 to 600 feet, Waukesha County was classified by state legislation as one of only two Groundwater Management Areas in the state. As such, access to groundwater resources could be curtailed or prohibited in order to protect environmental resources.

In addition to environmental policies set into law, our long-term water supply planning is based on consideration of long-term trends, scientific studies, and comprehensive regional planning. Our review of the best available information indicates the following:

• If less water is withdrawn from the deep aquifer and more from the shallow aquifer, then deep groundwater levels increase. However, reducing deep aquifer pumping and increasing shallow aquifer pumping produces adverse environmental impacts on wetlands and reduces baseflow to lakes and streams (See Volume 5 of the Application, Environmental Report).

• If less water is withdrawn from the deep aquifer when groundwater systems convert to a Lake Michigan supply, deep aquifer groundwater levels increase. This happened near Milwaukee, Brown County, WI, and Northeastern Illinois. However, the rebound of the aquifer was temporary as, over time, development drove more groundwater use and the deep aquifer declined again. The deep confined aquifer is not sustainable and it is not prudent to base long-term water supply planning on it.

• If Waukesha continues with groundwater supplies, it contributes to adverse environmental impact on shallow and deep aquifers.

Because of the resultant environmental impacts, the groundwater supply alternatives are not sustainable for the long-term.

In support of your review of Waukesha’s Application, I have tried to cooperate and provide you with requested information in a timely way. Despite the shared information, your recent article gave an unbalanced overview of our proposal. A few examples include:

• No mention was made of possibly the most relevant fact of all – that Waukesha has proposed to return at least 100% of the volume of water withdrawn, meaning Lake Michigan water is preserved and protected.

• No mention was made of the shale layer that restricts the recharge of our current primary water source.

• The 2050 population projection is incorrectly cited, creating a false impression of aggressive growth. The article cites the City’s current population of about 71,000, but later incorrectly says the City’s population will grow to 97,400 at buildout in 2050. The actual population projections at buildout are 76,300 for the City and 97,400 for the service area. While the population served increases by about 26,000, about 10,000 of this service population resides in the area today and is served by private wells (See Volume 2 of the Application, Water Supply Service Area Plan). The claim that the City is seeking water to allow sprawling growth is not supported by state and regional population projections. It is not supported by approved land use plans through 2035. With an actual projected population growth rate of 0.5% per year, statements like “The amount of water Waukesha seeks . . . is designed to allow the city’s sprawling growth pattern to expand” are not true. If you had asked about this issue, I could have provided you with the facts.

In addition, no mention of other relevant information about growth in our FAQs was provided in your article, including the fact that only 15% of the land in the service area is available for development.

Your website says, “Circle of Blue generates the fresh, objective reportage . . . while avoiding the ’advocacy’ label.” I hope that any further articles will, in fact, be more objective. Thank you.

As a taxpayer and farm owner in the State of Michigan I oppose this application for tapping into the Lake Michigan basin. Water conservation and intelligent use of current resources are much more preferable to establishing a new unprecedented use of the Great Lakes as a convenient means of fostering population growth beyond the basin boundaries. This is no more than a developers’ ploy to find a cheap source of water.