Amid California Drought, Oil Industry Wastewater Attracts New Scrutiny

State and federal authorities move to tame use of aquifers as oil field dumps.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

In the fourth year of an unrelenting drought emergency, every use of water in California is being put under the microscope. Watering a lawn, filling a pool, washing a car, growing food — all are familiar practices now viewed with a more critical eye.

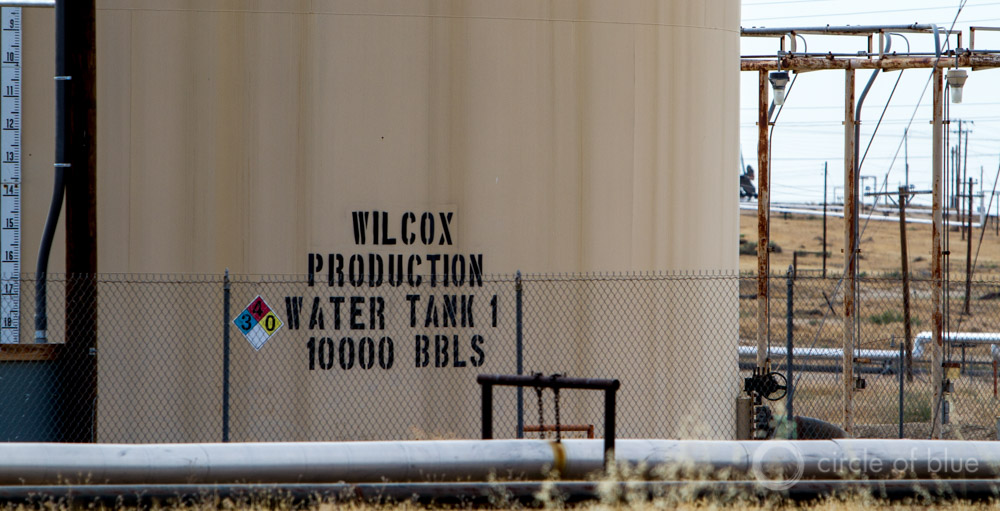

The same is true of California’s oil industry, the nation’s third largest. Centered in Kern County, at the southern end of the Central Valley, the industry’s relationship to water is bound by a surprising ratio. The main product, by volume, from California’s oil fields is not oil. It’s water. For every barrel of oil pumped from the ground, fifteen barrels of water, on average, come to the surface.

Another surprise, perhaps, for most observers is that hydraulic fracturing is not responsible for all that water. Fracking often stirs deep passions, but the drilling technique uses very little water in California, only 1.7 million barrels (70 million gallons) in 2014.

The more significant challenge is getting rid of what’s known in the oil industry as “produced water,” the chemical- and salt-laced liquid byproduct found in the same deep geologic zones that contain oil and natural gas. When wells are drilled to the depth of the hydrocarbon reserves, a torrent of produced water, typically millions of gallons, rushes up the borehole to the surface.

Disposing of so much produced water, which generally is saturated with toxic compounds and salt, has proved problematic. In the last year, federal and state audits in California found a number of injection wells and evaporation ponds — two primary methods of wastewater disposal — that were dumping water into protected groundwater sources or operating without permits. Though state officials say there are no documented cases of current drinking water sources being polluted by oil industry waste, the violations take on greater urgency during a historic drought in which even marginal waters are increasing in value. State regulators now face pressure from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and environmental groups to exercise tighter control over the oil industry’s wastewater.

Which Method of Disposal Makes Sense?

State authorities are dealing with two questions about the disposal of produced water. Should the tide of waste be dumped into aquifers or reused? And what sorts of monitoring and oversight are necessary to protect drinking water sources from contamination?

The goal of the increased scrutiny is to keep injected water in place. Steve Bohlen, the Department of Conservation’s oil and gas supervisor, said that the department is reviewing each of the questionable wells and requiring operators to submit data on the chemical composition of injected fluids, water quality in the aquifer, and the location of any nearby drinking water wells.

“Water injected into a disposal well, properly permitted, should have geologic confinement so the wastewater is not traveling long distances and is not mixing with water of higher quality,” Bohlen told Circle of Blue.

Though state officials are acting with renewed vigilance, critics say that their remedies are too slow or too timid.

“The state is starting to deal with these issues whereas in the past they were ignored,” Andrew Grinberg, an analyst at Clean Water Action, told Circle of Blue. Clean Water Action published a report in November 2014 on the pollution threats that unlined disposal ponds pose to air quality and groundwater.

But Grinberg said that the drought, which is forcing the state to justify the use of every drop of water, requires authorities to take stronger action, such as immediately halting injection in illegal wells or banning the use of unlined ponds.

“The magnitude of these issues in a drought makes oil waste disposal a higher priority than the state is acknowledging,” Grinberg asserted. “While they are conducting an investigation, they are allowing discharge to continue. That response is lacking and inadequate.”

The Response

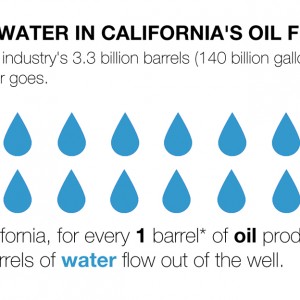

California’s oil industry produced 3.3 billion barrels (140 billion gallons) of wastewater in 2014, according to the state Department of Conservation. That’s more than 16 times the 204 million barrels of oil produced last year in California, according to the federal Energy Information Administration. Nearly two-thirds of the produced water is pumped back into the oil fields as steam or water, to maintain pressure in the wells and keep the heavy hydrocarbons flowing.

The remainder of the produced water — more than 1 billion barrels — goes in several directions. Nearly 30 percent is injected into the state’s roughly 1,750 underground disposal wells, the equivalent of throwing away the water because it is removed from the hydrologic cycle. Approximately 5 percent of the wastewater is dumped into evaporation ponds that speckle the desert flatlands of Kern County.

A small portion, less than 5 percent, is treated and sent to irrigation districts, to be blended with cleaner sources and used for irrigation. This practice — and the residual contaminants in the irrigation water — has invited greater scrutiny as well.

State assessments center on injection wells and evaporation ponds because they pose the biggest risk to groundwater.

Oil field wastewater is regulated as a Class II fluid under the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s underground injection control program, which is part of the Safe Drinking Water Act and is designed to protect drinking water sources from contamination. The EPA has granted 40 states the authority to oversee the permitting and enforcement of Class II wells under the underground injection control program. California earned this power, called primacy, in 1983.

Federal Intervention

Deficiencies in California’s injection well program, which is run by the Department of Conservation’s Division of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR), came to light last summer. EPA audits of the program in 2011 and 2012 found an unspecified number of wells that were injecting wastewater into protected aquifers. Those results were shared with DOGGR, which followed with its own analysis. In a letter dated July 17, 2014, and sent to the leaders of the California Natural Resources Agency and the California Environmental Protection Agency, officials in the U.S. EPA’s Region 9 office asked for a comprehensive review of the state’s injection well program.

One of the key tests for protection is water quality in the receiving aquifer, as measured in total dissolved solids (TDS). Federal regulations protect aquifers with less than 10,000 parts per million TDS. Drinking water, by comparison, is typically less than 300 parts per million, so the standard is designed to guard a range of waters that might be too salty to use today but, with adequate treatment, could be future water sources.

DOGGR officials are now reviewing the failed permitting system. Analysis completed since receiving the EPA letter in July determined that 452 wells — roughly a quarter of the wells operating in the state — injected wastewater into aquifers that should not have been used as an underground garbage can.

One hundred fifty-five wells were injecting into aquifers with less than 3,000 TDS. Regulators have closed 23 of these wells. The remainder must close by October 15 or ask the state for an exemption. Bohlen said that the state is unlikely to grant any exemptions, though a few are possible. An aquifer can be exempt if well operators prove that the water is saturated with hydrocarbons, if it is too deep for economic use of the water, or if there is no reasonable expectation that it could serve as a public water supply.

The 297 wells that are injecting into aquifers with TDS between 3,000 and 10,000 parts per million must close by February 15, 2017. Regulators are conducting more thorough assessments on 207 of these wells because they are injecting water relatively close to the surface – at depths of less than 457 meters (1,500 feet). As groundwater tables have declined during the drought, these formerly marginal sources of water are now becoming more valuable and may need additional protection.

The reassessment is a difficult task, the EPA noted. “Our frequent dialogue and your efforts in the last six months have illuminated the breadth and complexity of the challenges and the substantial workload faced by the State Agencies in overcoming the program’s deficiencies,” wrote Jane Diamond, director of the EPA Region 9 water division, in a December 22, 2014 letter.

Still, the timetable for action is too slow for a host of environmental groups. Earlier this month, the Center for Biological Diversity, Earthjustice and the Sierra Club filed suit against DOGGR, seeking to shut down the 452 injection wells.

State Reforms Proposed

Lawmakers are pushing reforms as well. This week, the California Assembly Appropriations Committee will debate AB 356, a bill that adds new groundwater monitoring requirements for disposal wells. It was approved by the Natural Resources Committee by a vote of 6 to 2. The groundwater monitoring bill follows SB 1281, a law passed last September that strengthened reporting standards for the oil industry’s wastewater practices. The first deadline to report water volumes, chemical compositions, and use of recycled water under SB 1281 comes in June.

Lawmakers have other options for action. Asked if the Department of Conservation would write regulations that would force the oil industry to clean up and recycle more of its wastewater rather than inject it, Bohlen, the oil and gas supervisor, said that such an action would be beyond the department’s authority.

–Steve Bohlen, oil and gas supervisor

California Department of Conservation

“Creating financial incentives through regulations is a policy call,” Bohlen said. “That’s for the administration or the Legislature and would not be in our bailiwick.”

Bohlen expects that injection wells will be part of the industrial cycle in California for the foreseeable future. Though companies are developing recycling technologies that eliminate discharge, there are no commercial operations yet in California. The most common technology today, called reverse osmosis, produces one gallon of concentrated brine for every gallon of pure water. Even if recycling increases, the brine remains a problem.

“No disposal wells at all is not something that you can have if you want to have oil production in the state,” Bohlen said. “These two go together.”

Waste Ponds Also Assessed

Evaporation ponds, the second disposal method, are also receiving a closer look. The Central Valley Regional Water Quality Control Board’s Fresno office, which has jurisdiction over the state’s prime oil-producing territory, is requiring evaporation pond operators to submit water quality tests by June 15 for the 619 active ponds, meaning those with fluid in them. All active ponds are being reviewed and must be properly permitted by December 2016 or face closure, according to Clay Rodgers, the Central Valley regional official in charge of oil wastewater.

Last spring during a field inspection, officials at the Central Valley Regional Water Quality Control Board found disposal ponds that they were not aware of. Disposal ponds range in size from a corner office to a football field. Some are lined to prevent waste from seeping into the ground; others are not.

“We said to ourselves that we need to look more closely at this,” Rodgers told Circle of Blue.

Rodgers and other officials looked at aerial photographs, conducted more field inspections, drew more information from the DOGGR database, and called oil companies. They concluded that the waste ponds needed a comprehensive review.

The office has filed 95 enforcement orders against unpermitted ponds. These orders will all be heard by the end of the year, and the pond operators will have until December 2016 to comply with permit requirements such as water quality standards, sampling and reporting schedules, and prohibitions on storing hazardous waste.

The office did not have enough money to handle the assessment on its own, Rodgers said. It had to pull in people from other programs to work on the inspections and enforcement. The governor’s next budget offers some assistance – funding for six new staff positions to address the ponds, Rodgers said.

The highest priority ponds are on the east side of the San Joaquin Valley where groundwater has a greater chance of contaminating farm fields or drinking water wells. As with injection wells, Rodgers said he does not know of any drinking water wells contaminated by seepage from waste ponds. At least one farm in Kern County, however, has suffered polluted groundwater. In 2009, a jury ordered Aera Energy, a Bakersfield company, to pay Fred Starrh, an almond grower, $US 9 million in damages resulting from oil wastewater that was dumped in unlined ponds and spoiled his orchards.

For Grinberg and his Clean Water Action colleagues, the waste ponds are an example of an outdated practice that should be banned. But state officials are not willing to take that step. For Rodgers, the goal is simple: to keep the waste in the ponds.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Leave a Reply

Infographic: Wastewater in California’s Oil Fields

Infographic: Wastewater in California’s Oil Fields

According to Bill Mckibben, the ideal parts per million of Carbon in our atmosphere would be 350ppm, that was in 1975. Now we our at 404ppm and rising, we have a Atmospheric budget of 556 Billion Toxic Tons of Carbon to emit and then we would increase Temp. to 2C, this was in 2012. that leaves us with 406 Billion more Toxic Tons to burn, which would bring us to 2019 – 2020. What will the Temp. be then ?

In the 1850s parts per million of carbon was 260 – 280.

Right Now we have 404 parts per million of carbon in our Atmosphere, the Arctic is 75% gone and Melting, Greenland and Antarctica are calving. The North west Pacific Ocean is 5-8 degree warmer than normal. Whales, Dolphins, Sea Lions, Starfish, Die Off along the Western Coast of the Pacific Ocean over the past year .

“Ice sheets contain enormous quantities of frozen water. If the Greenland Ice Sheet melted, scientists estimate that sea level would rise about 6 meters (20 feet). If the Antarctic Ice Sheet melted, sea level would rise by about 60 meters (200 feet).” National Snow and Ice Data Center.

We emitted 40 -50 Billion Toxic Tons of GHGs Globally, in the United State we emitted 6.8 Billion Toxic Tons, and are leading the charge to Frack the Globe.

California emitted 459 Toxic Tons of Carbon Dioxide in 2014, Gov Browns call to reduce this to 1990 levels so we can continue to emit over 400 million Toxic Tons a year, will not help us stop or slow down Global Warming and Sea Levels Rising.

“Updates to the 2020 Limit.

Calculation of the original 1990 limit approved in 2007 was revised using the scientifically updated IPCC 2007 fourth assessment report (AR4) global warming potentials, to 431 MMTCO2e. Thus the 2020 GHG emissions limit established in response to AB 32 is now slightly higher than the 427 MMTCO2e in the initial Scoping Plan.” Ca. Gov. Data

We Need 100% Renewable Energies .

Cap and Trade Funds: California Incentive Electric Vehicle Program, Those who are considered by the program to be Low Income (225 percent of the federal poverty level or less) qualify for a hybrid that’s rated higher than 35 mpg, or $9,500 toward a plug-in hybrid or electric vehicle. Meanwhile, Moderate Income households (226 to 300 percent of the poverty level) qualify for $5,000 toward those hybrids, or $7,500 toward a plug-in hybrid or EV, and those who are considered Above Moderate Income (up to four times the federal poverty level) can get $5,500 toward a plug-in hybrid or EV.”The Federal Poverty Level for a family of four is an annual income of $24,250. Applying the program qualifying percentages:To qualify, you have to live in one of two problematic air-pollution zones: either the South Coast Air Quality Management District (covering some of Greater Los Angeles) or the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District.

Call 909 396 2647 for program details.

225% x 24,250 = $54,562.50

300% x 24,250 = $72,750

400% x 24,250 = $97,000

That “Above Moderate Income” household of four can make up to $97,000 and if they buy a new EV they get a $5,500 program payment + $2,500 CARB rebate + $7,500 Federal Tax Credit. Wow! ” SD_Steve

No Twin Tunnels, Save the Delta, this Fragile Eco-System is a measurement of our commitment to bring in Sustainable Energy Policies.

Cap and Trade Phased Out.

75% Airport reduction in Carbon emissions.

Ban Fracking

“Governor Brown is forcing ordinary Californians to shoulder the burden of the drought by cutting their personal water use while giving the oil industry a continuing license to break the law and poison our water,” said Zack Malitz of Environmental Group Credo.

Close all 108, for profit, Water Bottling Plants in California

Golf Courses should be on Gray Water or Closed.

Implement a California Residential and Commercial Feed in Tariff.

California Residential Feed in Tariff would allow homeowners to sell their Renewable Energy to the utility, protecting our communities from Poison Water, Grid Failures, Natural Disasters, Toxic Natural Gas and Oil Fracking.

Our California Residential Feed-In Tariff should start out at 16 cents per kilowatt hour, 5 cents per kilowatt hour to the Utility for use of the Grid, 11 cents per kilowatt hour going to the Home Owner.

A California Commercial FiT in Los Angeles, Palo Alto, an Sacramento Ca. are operating NOW, paying the Business Person 17 cents cents per kilowatt hour.

Sign and Share this petition for a California Residential Feed in Tariff.

http://signon.org/sign/let-california-home-owners

I’m sorry, but I submit that the idea that fracking uses very little water is false reasoning. First, the number of wells is undisclosed. Who is doing the tracking and recording of this information (measuring, metering, monitoring the water)? We actually don’t have all the facts. The idea that it results in “produced water” (a euphemism for wastewater), another pollutant, is actually another part of the problem. This is wasted water. When California’s oil and gas is gone so, too, will our water disappear or be rendered useless unless we can stop now.

Daniel, these are real solutions. Thank you.

Kern County is the hub of oil production in California. Local government counts on oil production as their primary source of revenue. It’s important to put oil production in the right perspective and feel the need to share.

On 11/13/2012, I attended a hearing at Kern County. Prior to the regular agenda items, the Board of Supervisors heard complaints voiced by Shafter/Wasco commercial cherry and almond family farmers and their attorney about their wells being contaminated with hydraulic fracturing chemicals. (Farmers own the land but not mineral rights.) They were experiencing low yields and loss of trees.

Not a single supervisor spoke in favor of or mandated that the health department get involved in the case, nothing about testing the wells, aquifers to determine the scale of contamination or to suspend the product from being sold and placed on produce shelves.

For anyone interested in watching the official video and the dialog here it is.

To watch the testimony and discussion in its entirety, link to the video of Kern County Board of Supervisors hearing.

source. (http://www.co.kern.ca.us/bos/AgendaMinutesVideo.aspx#.UrH6udJDuSq)

Scroll down to 11/13/2012 2 pm hearing

Click on video line item. The video portion of the testimony from the attorney and farmers begins at right around 5 minutes.

Carol, I attended an annual meeting of a group called Smart Growth – Tehachapi Valleys, Sat. 5/30/2015. The Director at Kern County Planning stated to the crowd that fracking in California is not the same as in other states. I wrote down her statement. 690 fracking wells in Kern County using 200-300 acre ft of water.

1 acre foot = 325851.429 gallons

690 acre ft = 97,755,428.10000001 gallons H20

This is contrary to figures I heard at a hearing proposing a private water bank near Cantil, CA, above Mojave about a year 1/2 ago. Fracking of 1 well for 7 months uses as much water as a normal household uses in either 23 or 27 years – would have to look up notes on that one.

The normal household uses around 190 gallons a day.