Des Moines Initiates Clean Water Act Lawsuit to Stem Farm Pollution

Iowa’s largest city will sue three upstream counties to reduce nitrate contamination.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Iowa’s largest city earlier this month notified three counties upstream of a primary drinking water supply for 500,000 residents that it intends to file a federal lawsuit under the Clean Water Act to stem nitrate pollution in the Raccoon River.

In a challenge to contemporary farm cultivation practices that has potentially broad consequences for American agriculture, water quality, and the nation’s clean water law, the impending court action seeks to require Buena Vista, Calhoun, and Sac counties to apply the same federal permitting process to certain forms of farm pollution that industrial facilities must follow.

–Graham Gillette, chairman

Des Moines Water Works board

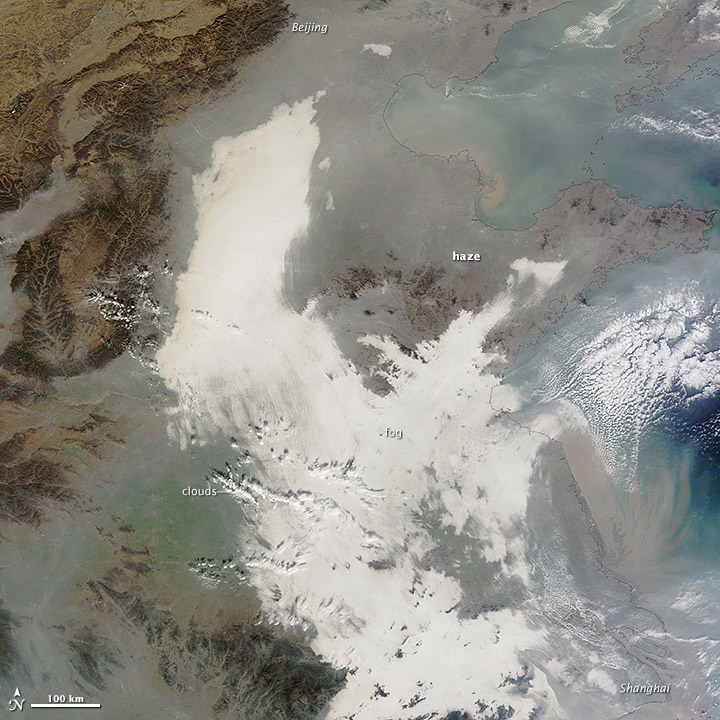

“I don’t have confidence that we’ve made any progress in Iowa in cleaning our water,” Graham Gillette, chairman of the Des Moines Water Works board, told Circle of Blue. “I don’t think any voluntary system will work. If we had adopted a voluntary system for air in the 1960s and 1970s, New York City would still look like Beijing today. We need some basic and achievable standards.”

The three counties have influential supporters who oppose Des Moines’ action. Iowa ranks second in the nation in farm sales at $US 30 billion per year and applies enormous quantities of nitrogen fertilizer to its cropland.

Governor Terry Branstad, a Republican, told the Des Moines Register editorial board that the city had “declared war on rural Iowa.”

John Torbert, executive director of the Iowa Drainage District Association, told Circle of Blue, “We feel that voluntary methods are a better way to affect change than through regulation.”

The case itself could be a legal stretch said Robin Craig, a law professor at the University of Utah. Written into the Clean Water Act are two explicit exemptions for agriculture — exemptions for stormwater that runs off of fields, and for excess irrigation water, called return flows. “That’s the real question in these cases,” Craig told Circle of Blue. “Given those exemptions, how are you going to frame the argument so that it isn’t one of them?”

Even some green groups think that litigation is not the best option. The Environmental Defense Fund is promoting a program called Sustain that was launched in October by United Suppliers, a fertilizer wholesaler. Sustain leverages the buying power of big retailers such as Walmart to pressure farmers toward practices that reduce nutrient pollution. The market-based strategy gets results by persuading companies that buy raw materials to adopt higher production standards.

“A lawsuit generates attention and pressure, but the market is also a way to work collaboratively that isn’t a fight,” EDF’s Suzy Friedman told Circle of Blue.

Huge Test For Clean Water Act

In the face of such opposition Des Moines officials say they are intent on pursuing their case in court. The Des Moines lawsuit, if it’s successful, would have enormous consequences for the reach and enforcement of the 1972 Clean Water Act, the nation’s most important statute for clearing contamination from inland and coastal waters. The 43-year-old law requires sewage plants, manufacturers, and other industrial facilities to limit contaminants in their effluent. The Clean Water Act, and its enforcement by federal courts, transformed urban waterways from cesspools into civic assets.

But agriculture was exempted from the Clean Water Act because farms were considered “non-point” sources of pollution — pollution that did not come from a pipe. Since the 1970s, large animal feedlots were brought under the act’s permitting requirements.

Other updates to the law have added new benchmarks for water quality in rivers. The benchmarks, called TMDLs, set standards for nitrate pollution that apply to agriculture as well as industry. But TMDL standards are overseen by the states and most actions for farmers are voluntary.

No state, as a result, has corralled water pollution from farms, said Justin Pidot, an assistant law professor at the University of Denver who studies the Clean Water Act.

“I don’t know of any state model that has been tremendously successful,” Pidot told Circle of Blue. “State and federal government haven’t been able to get a handle on this problem. Wherever you have agriculture, you usually have water pollution problems.”

Agriculture accounts for 90 percent of Iowa’s nitrate pollution, according to state figures. The Des Moines lawsuit is aimed at drainage districts, which are overseen by county boards of supervisors, and use a system of tiles and pipes to clear excess water that would hamper farm productivity. Des Moines is located in a particularly soggy wedge of Iowa where drainage districts are common. Roughly one quarter of the state is drained, according to the Iowa Drainage District Association, a trade group, and many of the districts are located northwest and upstream of Des Moines.

In their function and design, Des Moines argues, drainage districts are no different than urban utilities that channel stormwater into streams. Des Moines contends that drainage districts should be regulated like a wastewater treatment utility. It does not argue that all farm runoff should be classified as a point source — only the piped subsurface drainage, which is common in the Corn Belt states of Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and southern Minnesota.

Condition of Des Moines’ Water Worsens

Des Moines officials say they had to do something to deal with nitrates in the city’s drinking water. The Raccoon River in central Iowa is one of the city’s primary sources of drinking water. Measurements of nitrates, a common ingredient in commercial fertilizers, are typically highest in the growing season — in late spring and early summer after farmers seed the fields and feed nutrients to the plants.

In recent months the Des Moines Water Works noticed an unusual wintertime spike in the city’s water supply. Nitrates, which cause blood disorders and can be fatal to infants, were well above the federal government’s 10 parts-per-million standard for drinking water. The nitrate surge forced the utility to switch on equipment for removing the pollutant, at a cost of $US 4,000 per day. The machinery has been running constantly for nearly seven weeks.

“It’s unprecedented for this time of year,” Graham Gillette told Circle of Blue.

If the high nitrate levels were an aberration, they might be ignored. But the record-breaking swell is emblematic of a deeper, more pervasive problem that afflicts not only the Iowa capital but the Mississippi River Basin, the Gulf of Mexico, the Great Lakes, and farm regions and water bodies across the United States. More than four decades after the Clean Water Act was enacted, water pollution in many communities downstream of intensive agriculture is getting worse.

Nitrate pollution in the Mississippi River Basin, which includes Iowa, grew by 14 percent between 1980 and 2010, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, leading to rising utility costs and aquatic dead zones in the Gulf of Mexico the size of New England states. In Lake Erie in August, a toxic algal bloom, pumped up by phosphorus and nitrogen from upstream farms, prompted Toledo officials to shut down the public water system for three days. In rural California, groundwater, often a relatively pure source, is undrinkable without treatment for millions of people because of decades of nitrate poisoning.

Des Moines’ water supply is not an icky green muck, à la Erie. But the utility is tired of waiting for better days. Without changes in the status quo, dealing with the nitrate problem could become even more expensive for Des Moines.

Des Moines built its $US 4 million nitrate-removal facility in 1992, the year that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency restricted nitrates in tap water to 10 parts per million. Gillette said that the utility has contemplated building a second denitrification facility, to expand treatment capacity. That project would cost urban ratepayers between $US 80 million and $US 180 million, he said.

Lawsuit Forthcoming

The investments will nibble at the problem, but Gillette feels that without a bigger regulatory bite, the Raccoon River, the state of Iowa, and the entire Mississippi River Basin will continue on the path of failure.

According to the law, there is a 60-day waiting period between notifying parties of the intent to sue and filing the lawsuit. The interim period allows the two sides to seek resolution outside of court. Asked on Monday if he foresaw any circumstance in which the utility would not follow through with legal action, Gillette said no.

“I think we can make significant progress,” Gillette said. “The problem isn’t so dire that it’s hopeless. We just need to have a serious conversation about it.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Hello from Sac County , Iowa . I live on a farm . Much of the land my family farms was once marshes and shallow lakes . The drainage system is extensive . The social system is fragile .

Take care with the sorrows we live with . Yes , ask for a clean river .