Great Lakes Water Quality Remains in Spotlight in 2015

Safe drinking water tops list of concerns.

By Codi Kozacek

Circle of Blue

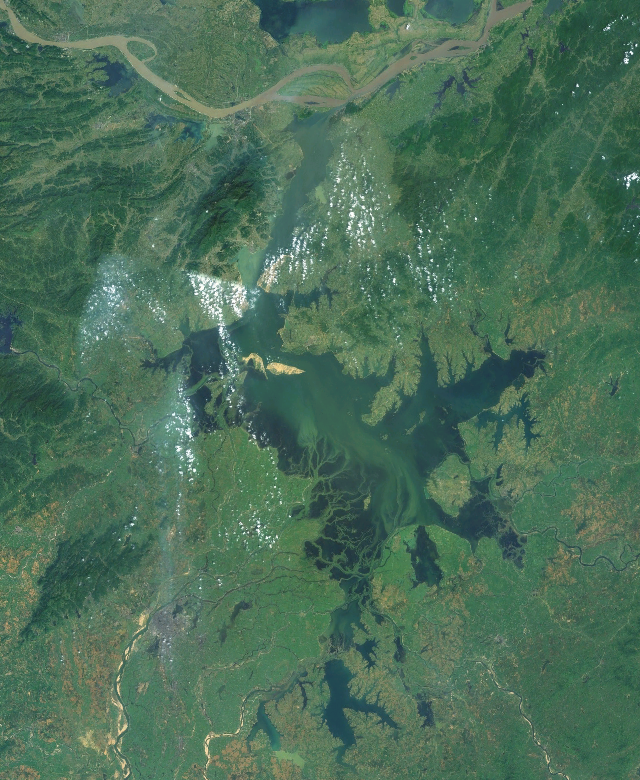

Following one of the region’s most dire public health crises—the 2014 toxic algae bloom in Lake Erie that shut down water supplies for half a million people in Toledo—2015 was a stark illustration of the range and severity of water quality problems in the Great Lakes that threaten people and ecosystems.

The threats are widespread. Lake Erie experienced this summer its largest ever outbreak of toxic algae, while blooms of the same algae species stretched along more than 1,000 kilometers (636 miles) of the Ohio River. In Flint, Michigan, researchers uncovered evidence that a switch in the city’s drinking water source is likely behind a spike in lead levels in the city’s children. The finding prompted a federal investigation of Michigan’s safe drinking water program. And in Wisconsin, a group of citizens asked the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to intervene after years of what they see as a systematic failure and dismantling of state water protection programs.

The challenges to safe water in the Great Lakes come at a time when water resources are being promoted as key to the region’s economic growth and as federal money continues to pour into the region through the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative. Congress is set to maintain the initiative’s funding at $US 300 million next year. Private industries are also spending heavily, with Great Lakes shipping companies committing $US 7 billion to build new ships, improve port infrastructure, and update locks and breakwaters along the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway.

Government leaders took several key steps in 2015 to safeguard water supplies. Most notably, they agreed to tackle algae blooms in Lake Erie and to increase scrutiny of oil pipelines that cross the Great Lakes. But fundamental policy changes to protect water remain elusive, and several major projects to maintain the lakes’ health have stalled. More than a year after completing a study of ways to separate the Great Lakes from the Mississippi River Basin, the federal government is still relying on stopgap measures to halt the progression of invasive Asian carp, which could devastate native fish populations if the carp reach the Great Lakes. The U.S. and Canadian governments are also sitting on a proposed plan to restore coastal wetlands in Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River. The plan would increase the ebb and flow of water levels to mimic natural fluctuations.

Still, ensuring safe drinking water will be the defining challenge for the Great Lakes region next year. Flint’s lead-laden drinking water raised public alarm in much the same way as the Toledo algae bloom. Despite reconnecting to Detroit’s water system in October, the city still needs to update its aging infrastructure to fix the problem. The city’s mayor declared a state of emergency earlier this month in an effort to secure additional resources.

“We cannot sit by and let senior citizens, families, and individuals go without access to clean water,” Julie Plawecki, a Michigan state representative from Dearborn Heights, said in a statement following the introduction of a package of bills in November to guarantee safe water. “We can’t live without water, so it’s certainly appropriate to pass legislation that recognizes this by stating that access to clean water is a human right.”

Toledo Catalyzes Action on Algae Blooms

The 2014 Toledo crisis focused national attention on water quality issues and was widely acknowledged as a wakeup call for Ohio. By February 2015, state and federal lawmakers had mobilized more than $US 188 million in a bipartisan effort to reduce the risk of Lake Erie algae. The influx of money helped cities in the Lake Erie basin upgrade their water and wastewater infrastructure. It also funded algae research and monitoring, and assisted farmers in implementing management practices that reduce runoff of phosphorus, a nutrient found in fertilizer and manure that drives algae growth.

New policies soon followed. In April, Ohio passed its first law regulating how and when farmers can spread fertilizer and manure on their fields, though it applies only to farmers in the state’s western Lake Erie Basin. The governors of Michigan and Ohio, along with the premier of Ontario, signed an agreement in June to cut the amount of phosphorus pollution flowing into western Lake Erie by 40 percent over the next 10 years.

Nonetheless, recent research gives a worrying prognosis for Lake Erie’s health. The number of harmful algae blooms is likely to double over the next century due to climate change, according to an Ohio State University study published this month. Less snow, heavier spring rainfall, and warmer temperatures are expected to provide ideal growing conditions for algae. The changing climate means the states may need to reduce phosphorus pollution even further than 40 percent to control the toxic blooms, the study’s authors said.

Reining in pollution from large livestock farms is a big part of the solution that has so far been overlooked, according to environmental organizations in Ohio. The largest farms, classified as concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), are regulated under the Clean Water Act. But many farms are too small to meet the CAFO threshold yet still generate nutrient pollution from manure, the groups argue.

Line 5 Subject to State Scrutiny

The revelation in 2012 of a section of oil pipeline crossing beneath the Great Lakes at the Straits of Mackinac resulted in intense public scrutiny. In 2015, state leaders responded. The Michigan Petroleum Pipeline Task Force released a report in July that raised significant concerns about the Line 5 oil pipeline and left the door open to the line’s potential closure.

In September, Michigan signed a deal with Line 5’s operator, Canadian energy company Enbridge, to prohibit the transport of heavy crude oil through the pipeline. Governor Rick Snyder also formed a state Pipeline Safety Advisory Board to carry out the task force’s recommendations, among them an analysis of alternatives to transporting oil through Line 5. Earlier this month, Traverse City-based water law and policy group For Love of Water (FLOW) presented an independent report to the board asserting that the portion of Line 5 that crosses the Straits could be decommissioned without negatively affecting energy consumers in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula or refineries in southern Michigan and Canada.

Concerns about other energy projects in the Great Lakes region also surfaced this year. A proposal by Canadian utility Ontario Power Generation to build a nuclear waste disposal facility near Lake Huron prompted a flurry of local resolutions against the project. Federal and state lawmakers from Great Lakes states have criticized the plan, and the Canadian government postponed a decision to approve or deny the proposal until March 1, 2016.

Also on the horizon is a pilot project to build the first offshore wind farm in Lake Erie near Cleveland. The project’s prospects improved earlier this month after a European wind developer agreed to build the $US 120 million installation.

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!