Q&A: Sarina Prabasi on the Sustainable Development Goal for Sanitation

Sarina Prabasi is the CEO of WaterAid America, part of the international organization WaterAid working to improve access to safe water, sanitation, and hygiene. She talks with Circle of Blue about the Sustainable Development subgoal to achieve universal and equitable sanitation access.

In a series of Q&As with water experts, Circle of Blue explores the significance of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for water, how they can be achieved, and how they will be measured. We spoke with Sarina Prabasi of WaterAid America about the 6.2 subgoal, which aims, by 2030, to “achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all, and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations.”

Sarina Prabasi: I think that women and girls have unique needs as well as challenges related to water and sanitation. When girls, and when women, don’t have access to sanitation and hygiene, it affects them in different ways than it does men, for example. In many of the places where we work, women have to travel far distances in order to find a safe and private place to go to the bathroom. There’s no toilets, and the ones that there are are often, in urban areas they could be very crowded, communal latrines. In rural areas it may be open defecation, increasingly having to go further and further away. In many cultures there are also taboos around this. And there’s shame and lack of privacy. So women are going very early in the morning before daybreak, or they’re going late at night. And that makes them very vulnerable to violence, sexual violence, attack, injury, all kinds of things. It’s something that, I think, often people don’t think about that aspect.

And when it comes to also girls, young girls, girls who are in school, for example, not having adequate facilities for sanitation and hygiene, it has a huge impact on education and ability to stay in school. Because if there is no place to go to the bathroom — or in some places we see there is technically a bathroom, but it’s smelly, there’s no door, there’s no privacy — it’s not possible for girls to use them. If that means they have to go out in the fields, in the grasses behind school, that again makes them vulnerable to attack, harassment, rape, some very serious. As girls hit puberty and they start menstruating, not having a place to handle basic menstrual hygiene means, again and again we see girls drop out. Or, they just don’t attend for five days or a week out of a month, and obviously not going to school one week out of the month affects their educational results and their outcomes, and then eventually leads to higher and higher rates of dropout. So the implications of sanitation and hygiene, lack of access, are really manifold.

I think often we don’t think about that—there are so many other areas. I’m focusing right now on the physical violence and the links to education, but there are also links for women for health. With open defecation there is a lot more sickness in the community, and women are the caretakers. Women are the ones who have to take care of the sick children, sick family members. The disease burden of having open defecation and not having good sanitation and hygiene practices, women carry a much higher burden of being the caregivers. That, again, means that that takes them away from other opportunities. It’s an interesting situation because often we think about women and communities being as the primary caretakers of the family, decision-makers around caretaking and caregiving. So this lack of sanitation and hygiene really has a huge differential impact on women and girls.

Sarina Prabasi: In my mind, adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for women would actually look like girls staying in school and completing their education, women being able to be productive, have livelihoods, incomes, productive activities, healthier kids, healthier communities. I think that’s really the outcome of what it would look like. And, you know, we’ve made a lot of progress. I don’t want to underplay the progress that we’ve made, but sanitation has been one of the most off-track goals, in terms of the previous Millennium Development Goals. It was one of the most off-track, and it continues to be a big challenge. We’re very excited about the Sustainable Development Goals and Goal 6 for water, sanitation, and hygiene. I think that we are quite far away from that goal, but I think that with the will and the resources, we’re also in a place where sanitation has become a topic. Previously, it was very hard to even talk about sanitation in meetings or in public forums. You wouldn’t see it on the front page of a newspaper. And that’s really changed. I think that is, acknowledging the problem is obviously a very important part of addressing it.

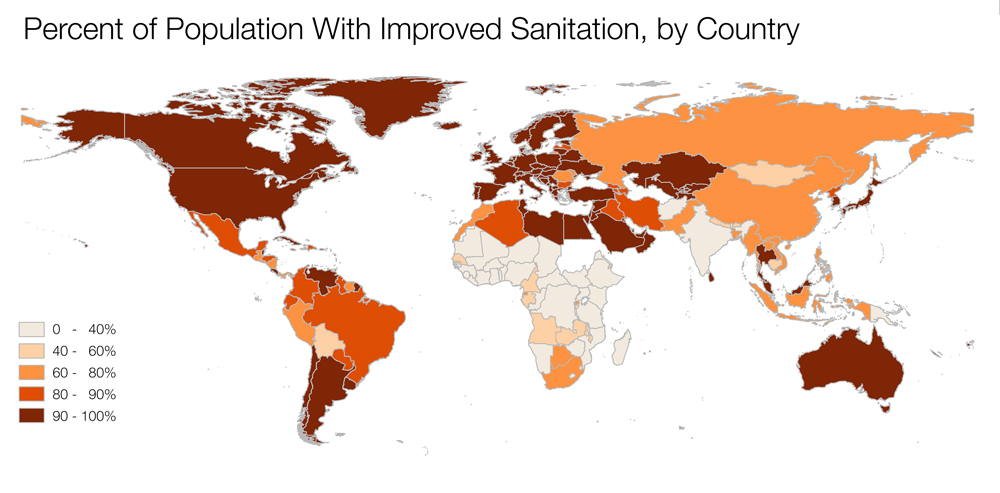

I think that the problem with sanitation and reaching the goal, I see that there’s a two-fold problem. One is the sheer numbers. So actually, when you look at the numbers, I think one country, India, makes up almost 60 percent of the total open defecation in the world, the number of people. So let’s say there’s a little bit over a billion people who practice open defecation, and 626 million of them are in India. So, that’s a huge number. That’s a huge percentage of the problem. I think there’s a UNICEF stat: 12 countries account for almost three-fourths of the people who practice open defecation. So on one hand there’s a numbers problem. There are countries where there are astonishingly high numbers of people practicing open defecation—not out of choice, but because of a lack of choice.

On the other hand there are countries that have made a lot of progress. For example, maybe some of the Latin American countries, but there are specific populations that are being left behind. There is inequality. When you look at the national statistics in some countries, overall statistics look great, but when you delve deeper and you look into a particular district or a particular department, that area, the statistics are a whole different world. So I think there are two sides of the problem. One is the numbers, the huge numbers, but the other side, which is increasingly important now with the Sustainable Development Goals, is the universal access. We’re not talking about reaching 80 percent of the people, or 90 percent, we want to reach everybody. So that last mile, as it’s so often called, that last 10 percent, that last 20 percent, I think that is also going to be a challenge. There are challenges on two sides of the equation.

Sarina Prabasi: I think the way it manifests is very different in rural and urban areas, but absolutely lack of sanitation is a huge problem in both urban and rural areas. Why is it a problem? It’s a problem on so many levels. On a very personal level, it’s a problem for personal dignity, privacy. Imagine just waking up in the morning and having to worry. It’s something that everybody has to do, and yet imagine the worry that you would wake up in the morning and you don’t know—you have to worry about where you are going to go. That stress, that indignity of not being able to take care of your basic human need, at a very personal level.

And then I think, there are huge problems, public health problems, water and sanitation-related diseases, and the fact that it’s preventable. Hand washing with soap is one of the most cost effective, proven ways to reduce disease, the spread of disease, and mortality and morbidity, and yet sometimes it’s the most simple things that get overlooked. It’s a problem on so many levels, from a very individual one to a public health system. Imagine if you could free up all the hospital beds where people are in hospitals and clinics for preventable reasons, things that could be prevented by having a decent toilet and access to water and soap for handwashing.

Especially maternal health, newborn health. It has, just ripple effects I think. In that sense, Goal 6, the water and sanitation goal, really cuts across many of the other Sustainable Development Goals. I think that water, we really look at it as a foundational thing. Without progress on this goal, we’re not going to realize progress on many of the other goals.

Sarina Prabasi: I think that the difficulties and dangers are really surprising. In rural Ethiopia, I spoke to a woman who told me that the thing she was terrified about were snake bites because she would have to walk out in the grasses and find a place to defecate. In other places, it’s sexual violence.

There are so many unnecessary challenges that women and girls face because of a lack of water and sanitation. It’s just, having water and sanitation doesn’t put an end to gender-based violence or sexual violence, but not having it makes women and girls, it adds to their vulnerability. It’s yet another source of vulnerability, going out. And there’s that shame associated with having to go and hide and find a place to relieve yourself. And you’re obviously going to be looking for secluded places, you’re trying to go out after dark because there’s that shame, and that just makes you that much more vulnerable to attack both from physical dangers like snake bites or wild animals if you’re in a rural area, or attack and harassment from men, or injury from falls and other things.

In our travels and work in all these countries, you hear some really desperate stories of women. And in urban areas sometimes it can be worse because urban areas in the developing world context are so, there’s not a lot of space. There’s not a lot of fields or open spaces or forests. The lack of privacy is really acute. It’s an acute problem in both contexts, rural as well as urban.

Sarina Prabasi: I think one aspect of it is listening to the voices of women and girls who are most affected. It reminds me of a conversation I had in a community in Ethiopia. The men in the village were saying, oh no, no, we have to pay user fees and this is too expensive, we don’t want to pay. And the women in the community were saying, no, we’ll pay. This is absolutely worth it for us. We will happily pay because it has improved our lives so much.

Part of it is in how we develop the solutions and who we’re listening to, but I think the other hurdle is managing the two sides of the problem that I was saying earlier. Paying attention to the places where the numbers are highest, so the top five countries or the top 12 countries that account for the great majority of open defecation and where the sanitation conditions are so poor, but at the same time also not forgetting that, in places where the general statistics look pretty good, those general statistics hide great inequality. Great, great inequality. So reaching those unreached and those hard-to-reach populations, at the same time as making progress on the big numbers, I think that’s going to be a real balancing act in terms of how we design programs, how we invest, where we invest, and how we go about tackling this issue.

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!