Report: Farming and Urban Growth Are Polluting U.S. Aquifers

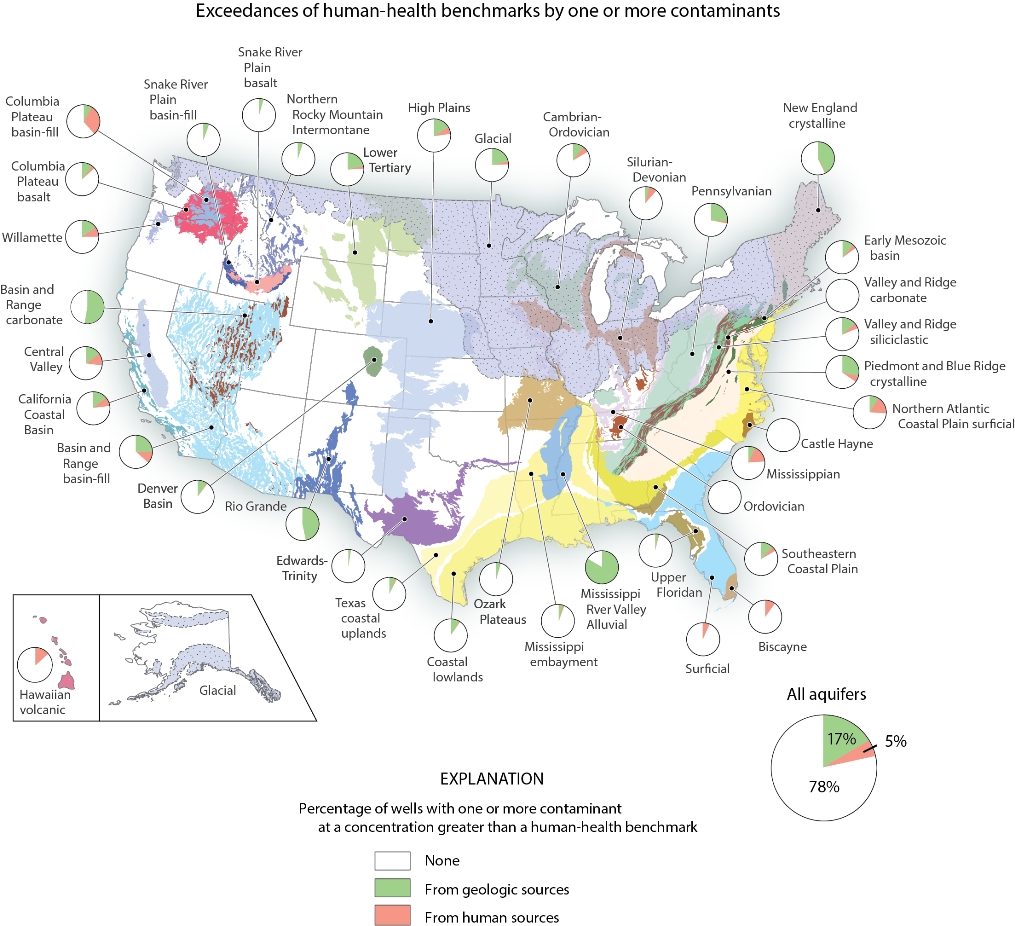

One-fifth of U.S. groundwater wells had at least one contaminant above federal standards for human health, according to new USGS study.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Farming and urban growth, two forces that are reshaping the land surface, are also changing the chemistry and physical properties of the nation’s aquifers, leading to greater concentrations of natural and man-made pollutants that could persist for decades in essential underground water sources, according to a comprehensive U.S. Geological Survey report, released on January 21.

Over the last two decades, according to the report, most of America’s 62 principal aquifers — which supply drinking water to more than 40 percent of the country and provide 55 percent of the nation’s irrigation water — have become dirtier. Two-thirds of the study areas saw an increase in the concentration of dissolved solids and chlorides, which are salts that can harm fish, or nitrates, which cause blood disorders in humans and can be fatal to infants.

The report, released on January 21, is a summary of more than 230 groundwater studies that sampled water from 6,620 wells between 1991 and 2010. The studies assessed water quality in aquifers that are used as a drinking water source, as well as in shallow aquifers beneath farmland and urban areas.

The restoration of groundwater supplies that have become contaminated is difficult, is costly, and can take decades.” — U.S. Geological Survey report

Water Quality in Principal Aquifers of the United States, 1991–2010

The most common sources of pollution are from naturally occurring elements that dissolve in water: arsenic, radium, and uranium. These pollutants appear most frequently in the Mississippi River Valley, the New England states, and the desert Southwest.

Nitrate, a byproduct of fertilizer, is the most prevalent man-made contaminant, occurring most frequently in central Washington, California’s Central Valley, and along the Atlantic coast from North Carolina to New Jersey.

Increasing nitrate levels are at the heart of a Clean Water Act lawsuit being prepared by the water utility that serves Des Moines, Iowa. The lawsuit challenges inadequate federal regulation of water pollution from farms.

Detecting pollution, however, does not mean it is harmful. The report also compared the concentration of each pollutant with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) benchmarks for the protection of human health. More than one-fifth of groundwater samples — 22 percent — had at least one contaminant that fell above federal standards. Another caveat: because the water samples used for the report were taken before the water was treated by municipal systems, the results do not indicate pollution in tap water. Private residential wells, however, are not subjected to federal standards and could be at risk if homeowners do not have treatment systems. Roughly 15 percent of Americans use water from private wells, according to the EPA.

As Above, So Below

The degradation of groundwater quality is due in large part to changes above ground.

According to the report, developed land in the United States increased 60 percent between 1982 and 2010 — in other words, an expanse of prairie, forest, and field the size of Oklahoma that was turned into lawns, homes, and roads. Lawn chemicals, salts that clear roads of ice, and the grime flushed from city streets can all end up in aquifers. On farms, fertilizer use doubled over the last four decades, lifting nitrate concentrations across the country.

All in all, levels of pesticides, nitrates, and other pollutants were highest in the upper layers of the aquifers. Because water seeps downward, often over decades, the contaminants will slowly add to the cost of purifying municipal drinking water, which is drawn from deeper aquifer layers.

“Over time, the changes that we see in shallow groundwater are likely to appear in the deeper parts of aquifers, as the shallow groundwater moves downward,” the report’s authors wrote. “This change in quality of deeper aquifers is a concern for the future because the restoration of groundwater supplies that have become contaminated is difficult, is costly, and can take decades.”

One Nation, Many Aquifers

Like the American landscape, the nation’s aquifers exhibit a diverse geology — from porous limestone in southern Appalachia to volcanic basalts in Washington’s Columbia Plateau. Each aquifer has different chemical properties. Naturally occurring contaminants such as arsenic are more common in the desert Southwest. Along the Atlantic and Gulf coastal plains, acidic groundwater — with a pH below 7 — is found and can increase susceptibility to radium contamination.

Moving water around changes the chemistry.” –Leslie DeSimone, U.S. Geological Survey

Physical properties vary, too. Water moves as fast as several feet per day in limestone regions, compared to feet per decade in the Great Plains, where the sediments are finer. This affects the lag time for pollution moving between shallow and deep layers. Slower movement means pollution today will take decades to show up in deeper sources.

The subterranean diversity makes generalization difficult. However, summarizing the hundreds of studies led to some interesting parallels.

Most surprising to Leslie DeSimone, a report author, was the relationship between groundwater use and groundwater pollution. Changes in the flow of water within an aquifer — by draining the land to plant crops, by irrigating land and adding extra moisture, or by pumping from deep within the aquifer and mixing different layers of water — alter the water’s chemical composition. That means the water could more easily absorb naturally occurring pollutants, such as radium or arsenic, or pick up man-made contaminants like nitrate at the surface.

“Moving water around changes the chemistry,” DeSimone told Circle of Blue.

And a lot of groundwater is moved. Each day, more than 288 million cubic meters (76 billion gallons) are pumped from aquifers for farms and cities.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] Reno County, where Pretty Prairie is located, is also an agricultural center. More than 97 percent of the county is classified as farmland. All public water systems use groundwater as their water source, as do households not on public water. Nitrate pollution is not a new phenomenon. A Kansas Geological Survey study from two decades ago fingered fertilizers as the culprit. Concentrations are higher near the surface, putting household wells and rural water systems at risk. The U.S. Geological Survey has measured rising nitrate concentrations in aquifers across the United States. […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!