Study: Fracking Water Use Varies in U.S. Oil and Gas Development

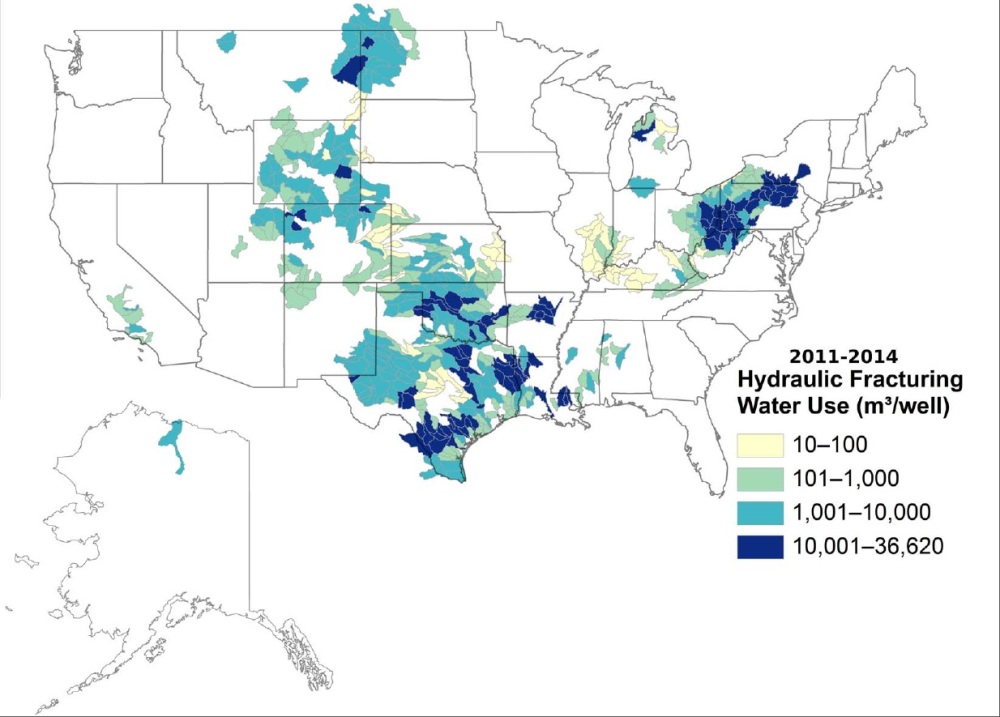

Shale gas basins in Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas, and the Appalachian region use the most water per well.

The volumes of water used in the United States to crack open underground shale layers that hold oil and gas are as varied as the American landscape on which the energy development takes place, according to a study from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) that provides one of the most complete maps to date of water use per well for hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. In addition, the amount of water needed to frack a well increased exponentially over the last decade, researchers found.

“Each basin is different, and each well is different,” Tanya Gallegos, a research engineer and the study’s lead author, told Circle of Blue.

The researchers combed an industry database and compiled information on nearly 264,000 wells drilled between 2000 and 2014. They found that horizontal wells — those that drill thousands of feet downward, then turn and run parallel to the surface — required significantly more water to frack than traditional vertical or slanted wells.

Over the last six years, fracking has revolutionized and revived the U.S. oil and gas industry, allowing drillers to tap hydrocarbons trapped in layers of shale rock and pushing production to levels not seen since the 1980s.

Most of these “unconventional” oil and gas deposits are located in the driest regions of the country, however, which has generated civic alarm about water use and pollution. This week, for instance, New York state formally banned fracking, the first state with significant shale gas resources to do so.

By aggregating water volumes per watershed, the researchers pinpointed which oil and gas basins needed the most water per well. The high-volume basins include:

- Eagle Ford (southern Texas)

- Haynesville-Bossier (Texas and Louisiana)

- Barnett (Texas)

- Fayetteville (Arkansas)

- Woodford (Oklahoma)

- Tuscaloosa (Louisiana and Mississippi)

- Marcellus and Utica (parts of Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and southern New York)

As production has increased, so have water volumes. Between 2000 and 2014, the median annual water volume used to hydraulically fracture horizontal wells increased from less than 670 cubic meters (176,995 gallons) to nearly 15,275 cubic meters (4 million gallons) per oil well and 19,425 cubic meters (5.1 million gallons) per gas well. The thirstiest wells, though, can require twice the median volume.

Vertical and directional wells require much less water to frack — on average, 2,600 cubic meters (671,000 gallons), or as little as one-seventh the volume required for a horizontal well. Roughly 42 percent of new fracked wells in 2014 were vertical or directional, according to the study.

Gallegos said that the research team did not investigate why the volumes used for fracking are increasing. The study also did not assess total water use, only water use per well, based on the IHS database, an industry resource that is not open to the public.

Fracking a well is only one segment of the water cycle in the new era of U.S. fossil fuel production. The researchers did not evaluate the others, such as the treatment and disposal of wastewater, which often involves prodigious volumes. California’s oil fields, for example, require very little water to frack: 530 cubic meters (140,000 gallons), according to the California Council on Science and Technology. But comparative gushers of water flow out of oil wells — for every barrel of oil that the industry produces in California, it generates 15 barrels of wastewater.

Still, Gallegos said that knowing the variation in water use is important for researchers and policymakers who are attempting to understand and regulate hydraulic fracturing.

“The information is important for asking the right questions,” she said.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!