Unstable Slopes: Nepal Landslide Highlights Risk to Lives and Infrastructure in Himalayas

Triggered by the April 25 earthquake, Kali Gandaki landslide reveals long-term challenges in the world’s highest mountain range.

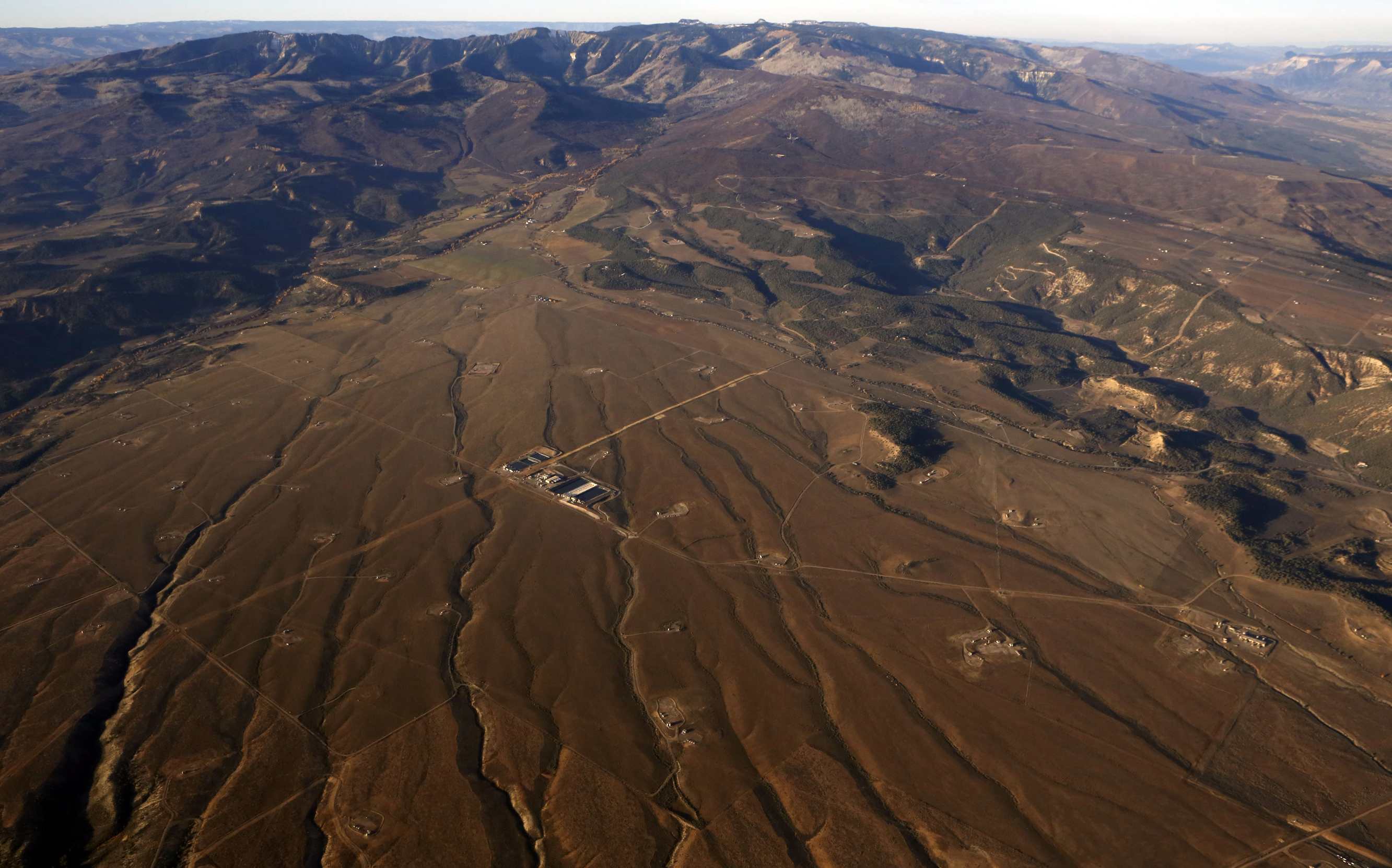

More than 3,000 landslides occurred in Nepal after the magnitude 7.8 earthquake on April 25. A slide on May 24 blocked the Kali Gandaki River, threatening homes and the country’s largest hydropower station. Photo courtesy of Doug Letterman / Flickr Creative Commons

The Himalayas are still unsettled more than a month after a devastating 7.8 magnitude earthquake in Nepal. Though the latest calamity ended without a loss of life, the landslide and flood that occurred over the weekend are a reminder that the valleys beneath the world’s highest mountain peaks are a dangerous place, both for people and for political dreams of hydropower wealth.

Early on the morning of Sunday, May 24, a riverside bluff collapsed in the Myagdi District of Nepal and blocked the Kali Gandaki River, a tributary of the Ganges and one of the country’s major rivers. The landslide — one of more than 3,000 that resulted from the April 25 earthquake and its many aftershocks — occurred in a steep gorge about 193 kilometers (120 miles) west of Kathmandu, the capital.

Rising quickly, a 100-meter-deep lake formed behind the dam, according to news site Ekantipur. The lake stretched for two kilometers (nearly a mile) upstream. Relief Web reported that 15,000 people in villages downstream were evacuated. According to the Nepal Police Twitter account, the landslide damaged one kilometer of Jomsom Highway, a mountain road.

Less than 15 hours later, the river breached the dam and inundated the valley. Below, YouTube footage shows the riverbed transformed from stagnant pools to torrential flood within minutes.

By Monday, 70 percent of the lake had drained. There were no reported casualties, though 15 houses were destroyed, according to My Repulica. On Thursday, the Nepal Army blasted the rubble in order to drain the remaining water.

Downstream, operators at the Kaligandaki hydropower station, Nepal’s largest, were on alert during the crisis. According to Ekantipur, operators shut down the 144-megawatt facility as a precaution.

Additionally, at least 14 hydropower dams were damaged by the April 25 quake, which killed 8,512 people.

Hydropower Risks

This is the second landslide in Nepal in less than a year to threaten hydropower stations. A slide last August above the Sun Koshi River, 80 kilometers (50 miles) east of Kathmandu, was more damaging. The avalanche of dirt knocked out 10 percent of Nepal’s hydropower capacity and killed 156 people.

Neighboring India knows similar pain.

A disastrous June 2013 flood in the mountain state of Uttarakhand killed at least 6,000 people and seriously damaged at least 10 large hydropower facilities.

Still, both India and Nepal hold big hopes for the power-generating potential of the deep valleys and fast-moving streams in the Himalayas. Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, visited Nepal last August to sign power transmission agreements and set up an office for the 5,600-megawatt Pancheshwar hydropower project on the Mahakali River.

Nepal’s total hydropower potential is estimated at 84,000 megawatts, but current generating capacity is less than 600 megawatts, which accounts for 93 percent of the country’s electricity supply.

Need for Alternatives to Hydropower

Critics of big hydropower projects caution that the April earthquake and the May landslide are fresh evidence for an alternative energy path.

Gagan Thapa — a member of Nepal’s parliament and chairman of the Parliamentary Committee on Agriculture, Energy, and Natural Resources — and Kashish Das Shrestha, a photographer and writer, argue that Nepal should reject big dams in favor of small-scale energy solutions that are suited to the unpredictability of a changing climate and that are less vulnerable to natural catastrophe.

“We believe Nepalis must pursue a new vision of energy security,” they wrote in an opinion piece published May 25 on The New York Times Dot Earth blog. “While hydro will remain important, we must shift to a more distributed and resilient system involving a mix of energy sources, microgrids, and net metering enabling individuals to contribute and profit.

“While the April 25 earthquake revealed our vulnerability, it also revealed the value of distributed energy systems. When the grid went offline after the quake, even in the capital the only public lights that stayed on were the new solar street lamps.”

In the meantime, the Himalayan threat will continue. The Kali Gandaki landslide was a dry landslide, meaning the slope collapsed without being weakened by moisture. With the soaking rains of the southwest monsoon approaching, the risk of landslides from saturated slopes will increase.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!