Zambia Electricity Shortage Highlights Africa’s Hydropower Shortfalls

Amid a changing social and environmental landscape, sub-Saharan Africa turns to its rivers.

By Codi Kozacek

Circle of Blue

Dwindling water reserves at the hydropower dams that provide nearly all of Zambia’s electricity could force grid operators to cut power supplies by 30 percent to the country’s copper mines, the keystone of its economy. The cuts represent a growing challenge in sub-Saharan Africa to match stagnant electricity supplies with rapid economic growth — a problem that many countries are betting on big hydropower projects to solve.

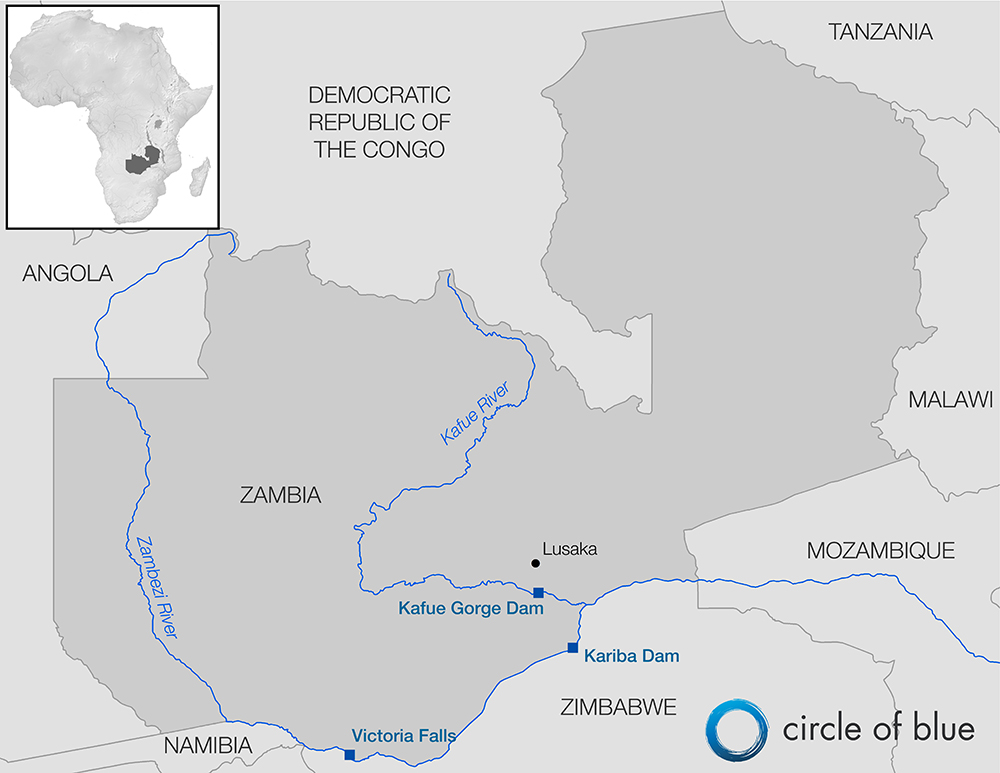

Zambia is a landlocked country with a population slightly larger than the state of Illinois and an annual gross domestic product less than the state of Vermont. It relies on hydropower for virtually all of its electricity generation, more than 90 percent of which is produced by just three major dams — Kafue Gorge, Kariba, and Victoria Falls.

Drought this year has left the country facing a 560-megawatt power deficit — equal to about one-quarter of its total generating capacity, Reuters reported. In May, the latest month data are available, water levels at the Kariba Lake reservoir were three meters (10 feet) below levels recorded at the same time last year. Furthermore, levels were declining during a time when they would normally be increasing. That month, the country’s national power utility, ZESCO, warned that it may cut power supplies by one-third, Bloomberg reported. The utility is now deciding whether to enforce the cuts for the mining industry, which is the second largest copper producer in Africa and consumes more than half of Zambia’s electricity. The country’s president has asked the utility not to cut power to the mines, according to Reuters.

Three decades ago, Zambia was a regional power exporter, but it has been unable to keep up with sub-Saharan Africa’s swiftly changing social, economic, and ecological landscape. Zambia’s population is growing 3.3 percent each year, one of the fastest rates in the world. In the past 10 years, its economy grew at an annual rate of 5 percent or above, and annual copper production increased 350 percent between 2000 and 2013. These factors, in addition to the poor financial performance of its electric utility, tightened the gap between electricity demand — which peaks at 2,000 megawatts — and a supply capacity of 2,200 megawatts.

Moreover, climate change is shifting Zambia’s water cycle. While total precipitation remains relatively consistent, rainfall intensity is projected to increase with longer dry periods between storms, according to a report by the Red Cross-Red Crescent Climate Center.

Large hydropower schemes, and the countries that rely on them for the bulk of their energy, are proving ill-equipped to deal with these changing conditions. Zambia regularly experiences power shortages and maintains a schedule of rolling blackouts. In June, Tanzania announced controversial plans to declare certain hydropower resources as protected sites, banning competition from other water users to reduce pressure from droughts. Last year, a severe drought in Brazil led to blackouts and cost the country $US 5 billion to subsidize more expensive fossil-fuel alternatives. Disastrous floods raged through the steep mountain valleys of India’s Uttarakhand state in 2013, taking thousands of lives and damaging at least 10 big dam projects.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the stage is set for a particularly fierce collision between energy development and the new realities of the 21st century. Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the most resource-rich and electricity-poor regions in the world, and both its population and its economic clout are mushrooming.

Power demand is expected to grow at 6 percent a year, according to the World Bank, while installed generating capacity has increased less than 2 percent a year over the past two decades. The World Bank estimates that, by 2040, the region will need 700 gigawatts of electricity capacity to meet demand — that is more than seven times what is currently installed.

–Heather Hoag, professor

University of San Francisco

Hydropower, as the region’s most abundant energy resource, is poised to play a starring role in this electricity revolution — only 8 percent of sub-Saharan Africa’s hydropower potential has been developed, the World Bank found. As of 2010, more than 70 dam projects capable of producing upwards of 80 gigawatts of power were either proposed, in the planning stages, or under construction in the region, according to river advocacy group International Rivers.

But many of the dams are legacy projects from Africa’s colonial past, and they are not always reevaluated under current conditions or with environmental and social consequences in mind.

“There’s really a need to come up with some effective solutions to the electricity problem in sub-Saharan Africa,” said Heather Hoag, a professor of environmental history at the University of San Francisco and an expert on the history of dam development in Africa, in an interview with Circle of Blue. “In that context, dams do seem very promising. The challenge is finding the right project and balancing the winners and losers — and this is about being transparent and taking into account the people who are asked to sacrifice the most: the riverine communities.”

Zambia’s Hydropower Push

Despite current and past problems with energy security due to its heavy reliance on hydropower — generation declined 30 percent during a drought in 1991 — Zambia is charging forward with an ambitious dam-development program. Hydropower projects currently on the table, many proposed for completion in the next 10 years, could increase electrical generating capacity by more than 6,000 megawatts. In comparison, the country added about 800 megawatts of capacity over the past 40 years.

The last time the former British colony pursued hydropower so fervently was in the mid-20th century. It brought the Kariba Dam online in 1960, four years before it gained independence, and completed the Kafue Gorge Dam in 1973. Hydroelectric stations at the dams each added about 1 gigawatt of power to the national grid and still account for the vast majority of the country’s electricity generation.

At the time, big dams were in vogue in Africa, even as their popularity declined abroad, Hoag explained.

“These dams become very important symbols of modernity, symbols of Africa’s entrance into the modern era,” she said. “They become important in terms of what they can offer — electricity, flood control, a steady supply of water for agriculture, and, in some cases, even tourism opportunities. On the other hand, there is a very important prestige factor that becomes central to some of Africa’s first generation of independent leaders, as demonstrations of these new countries’ ability to control their own destiny and jumpstart economic development that was held back during the colonial era.”

A surge in economic activity is also behind the latest push for big dam projects. Forecasts predict that, between 2010 and 2030, electricity demand in Zambia will grow an average of 4.5 percent each year, while supply will increase at an average rate of 3.9 percent annually, according to an analysis published in 2013 by the Human Sciences Research Council in Cape Town, South Africa. This follows a period of slow growth during the 1990s that inhibited infrastructure investments.

“In two decades, ZESCO has moved from a situation where a lack of demand growth adversely affected its financial position to one in which a lack of funds is preventing the capacity expansions required to serve rising demand,” the 2013 analysis said.

Who Benefits From Africa’s Big Dams

Demand for energy is tightly linked to the expansion of industrial activities, particularly mining. Zambia’s copper production has tripled in the past decade, while mining investments in sub-Saharan Africa are estimated to total $US 75 billion between 2013 and 2020, according to a 2015 report by the World Bank.

“Close to half of [sub-Saharan Africa] firms identify unreliable electricity as one of the biggest constraints to doing business,” the 2015 report said. “Pervasive outages cost about 5 percent in lost annual sales.”

Mining will demand more than 23 gigawatts of power by 2020, up from 15 gigawatts in 2012, according to the report. That demand would equal 35 percent of grid supply, if generation capacity were not expanded from 2012 levels. In Zambia, mining currently accounts for about half of electricity demand.

“Power-mining integration can create a win-win situation,” the 2015 World Bank report said. “Mining companies could be anchor customers for utilities, facilitating generation and transmission investments by producing the economies of scale needed for large infrastructure projects, in turn benefiting all consumers.”

Nonetheless, the report notes that sub-Saharan Africa must overcome a poor track record when it comes to sharing the benefits of large infrastructure projects with the wider population.

“The potential for power-mining integration is substantial, but there is little indication that such integration has benefited local populations in the past,” the report’s authors wrote. “In mineral-rich countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Guinea, Mauritania, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zambia, electrification rates remain below 20 percent.”

A key concern of human rights groups and conservationists is ensuring that new energy projects address not only industrial needs, but also the needs of surrounding communities and the environment. These concerns were largely ignored during the colonial and early independence period, when most of sub-Saharan Africa’s dams were built, though initiatives like the 1997 World Commission on Dams have since highlighted the importance of community consultation.

–Rudo Sanyanga, director

Africa Programs, International Rivers

“Over the years there’s been a debate over the development of safeguards to protect displaced populations, to protect the environment, and to ensure that the benefits are shared with the populations,” said Rudo Sanyanga, the director of Africa Programs for International Rivers, in an interview with Circle of Blue. “But there are a lot of problems with that when it comes to implementation.”

In March, for example, the World Bank announced a plan to overhaul the management and oversight of its resettlement practices after internal reviews found “serious shortcomings” in the way that it documented and implemented protection measures for communities displaced by major projects. Moreover, projects in Africa are being pursued by a widening array of investors who are based in developing countries like Brazil, China, and India; they are also vulnerable to government corruption.

“There’s a lot of misinformation, especially to the public,” Sanyanga said. “Also, for people who are far removed from the direct impacts, they are not fully cognizant of the challenges of people who are displaced or who suffer because of these projects. We don’t have governments that are fully accountable in most of the African countries. Democracy is not mature yet, and some governments make decisions based on individual interests, and that’s why there is a lot of corruption as well.”

Legacy projects developed during the colonial period — and that are now being taken off the shelf — further complicate efforts to safeguard human and environmental interests.

“We have to recognize from the beginning that most large dams in sub-Saharan Africa are colonial artifacts,” Hoag said. “They were conceived and planned under the guise of colonial authority. That does not necessarily mean that the schematics and blueprints are wrong, but we have to take into consideration the context when they came about, who they were conceived to benefit, and whether or not those conceptions are true to the needs and reality of today.”

Planning for Climate Change

One of the realities that dam developers will need to contend with is climate change. In 2011, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), part of the World Bank Group, released a study about climate change effects on hydropower generation in Zambia’s Kafue River Basin. Most of the country’s mining, agriculture, and population is concentrated in the Kafue Basin, which cuts an L-shape through the center of the country before emptying into the Zambezi River to the southeast of Lusaka, the country’s capital. The proposed $US 1.5 billion Kafue Gorge Lower Dam, slated for completion in 2019, could produce 750 megawatts of power on the river.

The IFC study found that average temperatures in Zambia are expected to rise 3 to 5 degrees Celsius (5.4 to 9 degrees Fahrenheit) by the end of the century. Changes to the water cycle are not so clear, with average annual rainfall staying relatively constant, but the likelihood of extreme rainstorms increasing.

“The small changes in annual average precipitation levels between the base period and the late-century period are not equally distributed within a year,” the study’s authors wrote. “The five months ranging from May to September have historically received little to no rainfall. In the presence of climate change, the months of October, November, and December are also projected to experience reductions in average precipitation levels.”

Depending on different greenhouse gas emission scenarios — large dams themselves can produce large amounts of methane — and the level of power development in the Basin, this could result in reduced power generation between 17 and 22 percent at the Kafue Gorge Lower plant in the early and mid-21st century. By the end of the century, however, it could actually increase power generation by 12 percent, the study found.

“These negative impacts highlight the need to view hydropower operations in a systemic manner within the Kafue River Basin, where climate change impacts will occur over time, in combination with continued development and population growth,” the 2011 IFC report concluded.

A World Bank spokesperson reiterated that hydropower projects must take climate change into account.

“Countries all over the world are dealing with rainfall variability resulting from climate change,” the spokesperson wrote in a statement to Circle of Blue. “At the same time, more than a billion people are still living without access to electricity. Hydropower has the potential to help countries reduce poverty, boost shared prosperity, and improve their energy security, but variable rainfall makes long-term hydropower planning critically important.”

Governments in Africa have been slow to acknowledge the need to adapt to climate change, according to Sanyanga of International Rivers. Instead of relying on big hydropower dams that are vulnerable to droughts and floods, International Rivers advocates for other forms of renewable energy and smaller hydropower projects that are cheaper and more readily available to Africa’s rural communities.

“Our governments have been slow to take up other diverse sources of electricity, especially renewables like solar and wind, which also don’t have to go on the main grid,” she said. “They have been relying for a long time on the centralized grid. Yet, if we had policies that promote individual access to electricity, mini-grids, decentralized grids that supply smaller towns, and so forth, instead of relying on the main grid, we would be able to increase the available electricity for people in the various countries.”

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

One Way to Ease California Drought: Recycle Wastewater For Irrigation

One Way to Ease California Drought: Recycle Wastewater For Irrigation

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!