Strength of New EPA Lead Rule Depends on Accountability

Expert panel recommendations are criticized for lacking teeth.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

The scandal in Flint, Michigan, erupting with galling revelations every day, is drawing national attention to the danger and prevalence of lead pipes in American water systems at the same time that the U.S Environmental Protection Agency is revising federal regulations for lead in drinking water.

The goal of the revision is to strengthen standards that were first issued in 1991, then tweaked in 2000 and 2007. It is needed. Water testing requirements under the current rule miss the most severe cases of lead pollution. Just over 8 percent of U.S. water systems have exceeded the federal threshold for lead. But if testing requirements were stricter, more than 70 percent of systems would be in violation, according to a 2014 study from Arcadis, an engineering consultancy.

Because the Lead and Copper Rule is one of the most complex and nuanced federal drinking water regulations and one of the most difficult to put into practice, the update has drawn keen interest from water utilities and state regulators, who must ultimately implement the changes, and environmental health groups, who are campaigning for tougher measures.

“There’s a mismatch between the goals of the NDWAC recommendation and reality.”

–Jennifer Chavez, lawyer

Earthjustice

The National Drinking Water Advisory Council (NDWAC), which consults with the EPA on regulatory matters, submitted in December its recommendations for strengthening the rule, which the EPA expects to publish in draft form in 2017. The council acted on the advice of a 15-member working group comprised of utility representatives, public health officials, researchers, and clean water advocates.

The council took what appeared to be a firm stance. It said that water utilities should be more proactive in replacing lead service lines, the pipes that branch off a main distribution line and deliver water to individual houses. Rather than simply preventing the lines from leaching lead by using chemical additives that form a protective internal seal, eliminating lead services lines altogether should be the national goal, the council stated.

It is a worthy aspiration that garnered acclaim. However, critics — while endorsing the council’s intent — contend that the substance of the proposal is lacking. The council, they argue, offered a vision of a lead-free future without providing the regulatory sticks to guarantee that utilities actually follow through.

“There’s a mismatch between the goals of the NDWAC recommendation and reality,” Jennifer Chavez, a lawyer with Earthjustice, told Circle of Blue. “The goal is replacement of lead service lines. The reality is that when homeowners are shown that they have lead service lines, they either do not or cannot replace them. The goal is lofty, important, and appropriate, but the mechanisms to get there are the same that have led to few full lead service line replacements.”

Other observers fear that the NDWAC recommendations are riddled with loopholes, waiting to be exploited. They argue that if the EPA accepts the council’s proposal in full, without adding stronger accountability, oversight, and enforcement, the changes would weaken public health protections, not improve them.

“The recommended changes would dilute the current rule and leave us vulnerable to missing widespread contamination,” Yanna Lambrinidou, a member of the NDWAC working group who offered its only dissenting opinion, told Circle of Blue.

She continued: “I’m concerned that the NDWAC recommendations build a regulatory mechanism based on an aspirational vision of utilities doing the right thing, rather than a regulatory mechanism to ensure that these lead service line replacements are actually done.”

A Dissenting Opinion

Most federal drinking water regulations require utilities to scrub water of pollutants at the treatment plant, before the water is sent into the thousands of miles of pipe that branch throughout a city. Uniquely, the Lead and Copper Rule requires utilities to measure water quality at the household tap. No other Safe Drinking Water Act regulation does so.

The current rule emphasizes the use of chemicals to fiddle with water chemistry so that lead pipes do not corrode. If that does not work, then utilities must begin replacing lead pipes. A utility must do so only if more than 10 percent of the water samples are above the federal “action level” of 15 parts per billion. Cities with a half million people or more may test fewer than 100 homes to comply with the law. Individual households may have exceptionally high lead levels, but the city is not required to act unless the number of contaminated samples eclipses the 10 percent threshold. The EPA acknowledges that there is no safe level of lead exposure, particularly for children, whose brain development is at risk.

That is the basic outline of the current rule. Its effectiveness depends on testing protocols, contested definitions, and regular monitoring, all of which are at the heart of the debate about revisions. NDWAC said the rule’s priorities should be flipped: replacing pipes must be the top objective. After all, the EPA’s stated objective for the revision is to “improve the effectiveness of

corrosion control treatment in reducing exposure to lead and copper and to trigger additional actions that equitably reduce the public’s exposure to lead and copper when corrosion control treatment alone is not enough.” In other words, keeping to the same basic playbook.

The revisions ought at least to bring the nation closer to lead-free drinking water, but that is not what Lambrinidou sees happening at the moment.

In her statement of dissent, Lambrinidou, an affiliate faculty member at Virginia Tech and the president of Parents for Nontoxic Alternatives, identified four areas of concern with the NDWAC recommendations.

First, the EPA ought to require utilities to evaluate more regularly the effectiveness of their corrosion control practices. Second, the revisions ought to mandate better public education about lead. If residents knew that the testing procedures do not ensure every home has safe lead levels, they might be more willing to test their water and agree to rid their property of lead pipes.

“We need to complement [the law] with public education so that people know what the claim of safety actually means,” Lambrinidou asserted. “It means that there is no large-scale contamination. It does not mean that the water in your house is safe to drink. People do not know this. The public education requirement in the lead rule leaves us in the dark. It’s quite a rotten rule. It requires us to be partially responsible for our health but it does not require us to be told what we need to know.”

“We need to complement [the law] with public education so that people know what the claim of safety actually means.”

–Yanna Lambrinidou, president

Parents for Nontoxic Alternatives

Third, the new rule ought to strengthen the testing procedure so that proper techniques are used and homes with the highest levels of lead are accounted for. Utilities can game the system by letting the tap run for several minutes to flush residual lead. Or by using small-mouthed bottles, which can be filled only when tap water flows at a trickle, another way to minimize lead. The few samples that they are required to take means that the worst cases of contamination may be overlooked. Lambrinidou cited a study presented in November 2014 at an American Water Works Association conference to support her point. That study found that 70 percent of public water systems would exceed the federal threshold for lead if they expanded their testing programs to include the highest-risk homes.

Fourth, the recommendation to eliminate all lead service lines should come with measurable targets and timelines to ensure that the work is completed. Also, the rule should ban partial lead service line replacements, Lambrinidou said. Partial replacements occur when the utility replaces only the segment of the line that runs from the distribution main to the meter. A 2011 EPA study found that doing so actually increases lead levels.

Lambrinidou was not originally a member of the NDWAC working group. Looking over the names of those selected, she became alarmed at the lack of on-the-ground experience with lead in drinking water.

Lambrinidou vowed to take action. She attended the working group’s first public meeting, on March 25, 2014, along with Paul Schwartz of Water Alliance, a clean water group, and pitched her concerns. She was invited the next day to be on the panel, she recalled: “I bullied myself in there.”

Lambrinidou’s concerns about the NDWAC recommendations were echoed by Elin Betanzo, a water policy analyst at the Northeast-Midwest Institute.

“There aren’t any measures to hold water utilities accountable and nothing to enforce it,” Betanzo told Circle of Blue, referring to the NDWAC recommendations.

Betanzo also has a long history with lead issues. She worked in the EPA’s Office of Groundwater and Drinking Water in 2002, when Washington, D.C. had its own lead contamination crisis, and was one of the first EPA staff members assigned to the D.C. case.

The experience was instructive. Last year Betanzo began to notice a pattern in Flint that was familiar: high lead levels being detected in drinking water, public agencies not being straightforward about the problem, and officials downplaying the danger of lead exposure.

Alarmed, she shared her concerns with Mona Hanna-Attisha, a friend since high school, on August 26. Hanna-Attisha, a pediatrician at Flint’s Hurley Medical Center, responded, initiating the study that found the number of Flint children with high blood lead levels had doubled since the city switched water sources.

Control v. Ownership: A Central Definition for Lead Rule

Chavez, the Earthjustice lawyer, mentioned another area in which the current rule could be strengthened: the definition of who controls service lines.

When utilities replace lead service lines, they are required to replace only the portion that they control. Service lines often run in segments: from the main to the meter, which is on public land, and from the meter to the house, which is on private property. The current rule defines control as ownership of the line. The common interpretation is that utilities own only the segment from the main to the meter.

It is a much narrower definition than EPA originally intended, Chavez said. The 1991 rule allowed control to be interpreted broadly, meaning utilities had the authority to replace the entire line — that was the presumption, even — and they could use ratepayer funds to do so. But that definition was slipped into the rule without an adequate public comment period. It was challenged successfully in court on technical grounds by the American Water Works Association. The EPA ended up using the narrower meaning of control.

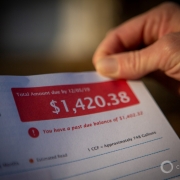

The definition matters. Many utility lead service line replacement programs focus only on the segment the utility owns. Homeowners are offered the opportunity to have their side replaced at the same time at their own expense, but most balk at the price tag: from $US 1,000 to $US 7,000. The result: partial replacements, which have been shown to increase lead levels.

The ramifications are evident in Washington, D.C., which began a lead service line replacement program in 2004 after its lead contamination crisis. Only 19 percent of the 19,895 replacements to date have been full replacements. The city even began scaling back its program after the EPA study on partial replacements, according to Nicole Kaiser, a DC Water spokeswoman. Nationwide, there are about 7.3 million lead service lines still in use in the United States, according to the EPA.

Chavez was disappointed that NDWAC did not recommend revisiting the question of control and ownership. She sent a letter to NDWAC and the EPA in November to argue her case.

“The definition is so key as to whether people have their lead service lines replaced,” Chavez explained.

Current Rule Could Have Prevented Flint

The irony in the matter is that even though Flint did not institute corrosion control, as is required under federal law, the EPA has not admitted that Flint violated the lead rule. City officials used sampling methods that are proven to minimize the detection of lead and it threw out samples with the highest lead levels in order to come in under the 10 percent threshold.

“EPA could enforce the existing law. It would have stopped Flint, would have stopped D.C.”

–Marc Edwards, professor

Virginia Tech

“It shows what a joke this regulation is,” Marc Edwards, a Virginia Tech professor, told a U.S. House Oversight Committee hearing on February 3. Edwards helped uncover lead contamination both in Washington, D.C. and Flint. “EPA could enforce the existing law,” he told the committee. “It would have stopped Flint, would have stopped D.C.”

Had the current rule been followed, the Flint disaster would not have happened. Still, some homes — up to 10 percent — could have had high lead levels without any corresponding action. That inadequacy is what clean water advocates hope the Lead and Copper Rule revision will address.

The EPA, however, has little to say about the debates surrounding the revision.

“EPA will carefully review these recommendations and other stakeholder perspectives as it develops proposed revisions to the LCR,” Monica Lee, an agency spokeswoman, wrote in a statement to Circle of Blue when asked about the NDWAC report. “EPA will also consider the lessons learned from the experience in Flint.”

Lee did not respond to a request to interview the EPA officials who participated in the working group meetings.

The agency expects to have a draft rule ready in 2017, according to Lee. That is too slow for some. In the wake of Flint, the languid timetable — publishing a draft rule some 13 years after the need for a comprehensive overhaul was identified — has opened the agency to criticism over the pace of reform.

At the House Oversight Committee hearing, Rep. Gary Palmer (R-AL) was bewildered by the length of the process.

“What are you waiting on?” Palmer asked.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!