Commentary: Great Lakes As Sacred Spaces

In the battle between sacred places and commerce, the sacred rarely stands a chance.

By Jerry Dennis

Special Contributor to Circle of Blue

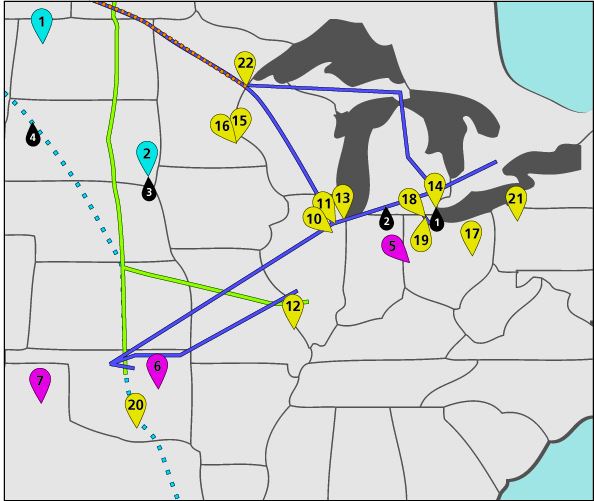

North America’s Great Lakes, which have suffered plenty from commerce, were also once sacred. The Ojibwe believed that Lake Superior, with the largest surface area of any lake in the world, was ruled by Misshepezhieu, the Great Lynx. That deity was both benevolent and malicious, fitting qualities for a body of water that can change from tranquil to furious in a moment. Those moods were a fact of life – still are – for anyone who lives in the region.

The Great Lakes are like five beautiful and charismatic sisters: willful, tempestuous, frequently charming, often dangerous, and ultimately unfathomable. As the main trade route to the interior of the continent and surrounded by lands flush with resources, the Great Lakes were central in transforming the U.S. and Canada into industrial and economic giants. Yet the lakes remain among the least appreciated of our major geographic features. No longer am I surprised to meet people who don’t know that the lakes are too vast to see across or that they contain most of the surface freshwater in North America. I am surprised, however, by the people who assume that all that water is there to be ransacked.

Maybe the lakes are too great for their own good. If they were contained entirely within Ontario or Michigan, they would be more ferociously defended. Instead they overlap two nations and eight states, and are constantly snarled in legislative complexities that make them vulnerable. And because they contain such an enormous volume of water — nearly a fifth of all that’s available on the surface of the earth – and are spread across a wide swath of North America many assume that they’re inexhaustible. With that much water, the thinking goes, there should be plenty for everyone.

Possibly that would be true if they were just storage bins. But they are vital ecosystems supporting complex communities of animals and plants, some of them found no place else, all of them dependent upon a consistent supply of clean water. Some of those communities are human: About 40 million of us live around the lakes, drawing our drinking water from them, swimming in them, fishing from them, boating upon them. Many of our cities sacrificed their environmental health to build the two nations, and have been abandoned for their troubles. Go to Gary or East Chicago or Hamilton, Ontario to see what the steelmills have wrought. The best hopes for those and dozens of other cities are the lakes themselves. Once they were just highways for shipping and dumping grounds for waste, but the current renaissance of waterfronts in Milwaukee, Duluth, Cleveland, Erie, Buffalo, Toronto, and many others makes it clear that we’ve entered a new stage in our relationship. The Great Lakes are no longer merely useful. They have become indicators of the quality of our lives.

The human tendency has always been to use and use until we use things up. But finally we’re realizing that some things are too important to be shoveled onto the conveyor belts of commerce until they’re gone. The Great Lakes are not merely reservoirs for the storage of water, that most useful of all substances. They are unique, living systems. Go to the shores of any of them, look across those miles of blue water stretching to the horizon, smell the wind, listen to the surf, and you might understand why they were once sacred. Is it too much to ask that we treat them as if they still were?

Jerry Dennis is the author of ten books about nature and the environment, including The Living Great Lakes: Searching for the Heart of the Inland Seas.

Circle of Blue provides relevant, reliable, and actionable on-the-ground information about the world’s resource crises.

The great lakes are great. It took along time to pollute them. The clean-up, if at all intended, would take longer.

However, we do not intend to go back to Ojibwe life-style. We have to balance development & comfortable life-style with environmental purity. As legislations in this respect would be futile, we aim at creating a ‘water-sensitive’ society in which each individual or family would decide how much reduction in the ‘comfortable life-style’ is voluntarily possible for the sake of environment. The first step would be to keep a family audit of resource consumption ( electricity, water, gas and food) and avoid wastage.