How the West’s Energy Boom Could Threaten Drinking Water for 1 in 12 Americans

By Abrahm Lustgarten

ProPublica

David Hasemyer

The San Diego Union-Tribune

This story was co-published with the San Diego Union-Tribune and also appears in that newspaper’s Dec. 21, 2008 issue.

The Colorado River, the life vein of the Southwestern United States, is in trouble.

The river’s water is hoarded the moment it trickles out of the mountains of Wyoming and Colorado and begins its 1,450-mile journey to Mexico’s border. It runs south through seven states and the Grand Canyon, delivering water to Phoenix, Los Angeles and San Diego. Along the way, it powers homes for 3 million people, nourishes 15 percent of the nation’s crops and provides drinking water to one in 12 Americans.

Now a rush to develop domestic oil, gas and uranium deposits along the river and its tributaries threatens its future.

The region could contain more oil than Alaska’s National Arctic Wildlife Refuge. It has the richest natural gas fields in the country. And nuclear energy, viewed as a key solution to the nation’s dependence on foreign energy, could use the uranium deposits held there.

But getting those resources would suck up vast quantities of the river’s water and could pollute what is left. That’s why those most concerned are water managers in places like Los Angeles and San Diego. They have the most to lose.

The river is already so beleaguered by drought and climate change that one environmental study called it the nation’s “most endangered” waterway. Researchers from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography warn the river’s reservoirs could dry up in 13 years.

The industrial push has already begun.

In the eight years George W. Bush has been in office, the Colorado River watershed has seen more oil and gas drilling than at any time in the past 25 years. Uranium claims have reached a 10-year high. Last week the departing administration auctioned off an additional 148,598 acres of federal land for gas drilling projects outside Moab, Utah.

As still more land is leased for drilling and a last-minute change in federal rules has paved the way for water-intensive oil shale mining, politicians and water managers are now being forced to ask which is more valuable: energy or water.

“The decisions we are making today will be dictating how we will be living the rest of our lives,” said Jim Pokrandt, a spokesman with the Colorado River Conservation District, a state-run policy agency. “We may have reached mutually exclusive demands on our water supply.”

Some experts and officials say the economic and ecological importance of the Colorado is just as vital to American security as the natural resources that can be extracted from around it.

“Without (the Colorado), there is no Western United States,” said Jim Baca, who directed the Bureau of Land Management, or BLM, in the Clinton administration and says the agency’s current policy is narrow-sighted. “If it becomes unusable, you move the entire Western United States out of any sort of economic position for growth.”

Balancing that risk with the need for energy is complicated, because scientific understanding of the Colorado is limited and no single agency manages the river as a national resource.

The Interior Department, which includes the BLM, oversees where the water goes, but not how it is kept clean. The EPA is charged with maintaining water quality, but it can’t control who uses it and doesn’t conduct its own research. Furthermore, the EPA delegates much of its authority to the states that the river runs through, and the federal, state and local authorities in charge of separate aspects of the river don’t always coordinate or cooperate.

“I don’t know that there is, quite honestly, anyone that looks at an entire overview impact statement of the Colorado River,” said Robert Walsh, a spokesman for the Bureau of Reclamation, which governs the allocation and flow of the southern part of the waterway.

Oil and natural gas drilling in Colorado already require so much water that if its annual demand were satisfied all at once, it would be the equivalent of shutting off most of Southern California’s water for five days. If Colorado’s oil shale is mined, it would turn off the spigot for 79 days.

Although company executives insist they adhere to environmental laws, natural gas drilling has led to numerous toxic spills across the West. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, mining has contaminated four out of 10 streams and rivers in the West. Similarly, mining has topped the government’s list of the most polluting industries for the past decade, and new mine problems continue to arise today.

Industry representatives and the Bush administration say breaking America’s dependence on foreign oil makes using all available energy resources here at home a priority.

“I believe this country needs to offer domestic resources to be energy independent,” said Tim Spisak, a senior official who heads the BLM’s oil and gas development group. “The way to do that is to responsibly develop public resources on our lands.”

Critics of Bush’s energy policies said they favor business interests at a time when climate change demands a fundamental shift in the way the nation values water. They also complain that the administration doesn’t grasp the West’s looming water problem.

“When Lake Mead goes dry, you cut off supply to the fifth largest economy in the world,” said Patricia Mulroy, general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, referring to the reservoir that sits behind the Hoover Dam and controls water flow to the Southwest’s cities. She points out that while some dispute the timing of Lake Mead’s demise, no one says it won’t happen.

“We’ve ignored the need to adapt,” Mulroy said. “We’ve never looked at what the secondary impact of, say, an energy decision is.”

Both the U.S. House and Senate are considering bills that would require better management of the nation’s water quality and water assets. But the bills focus more on the threat of climate change than the threat of industrial development. A growing number of water professionals say even a congressional act isn’t enough to clarify the government’s responsibility. They want the president to appoint a new national water authority — or even a cabinet-level water czar.

“If you are really going to deal with water, the nation needs to deal with it in a far more comprehensive manner,” said Brad Udall, director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s water assessment program at the University of Colorado. “We can’t afford to play around with potentially damaging activities.”

The Southern Nevada Water Authority, the state of Arizona and the Metropolitan Water District, which governs the water supply to Los Angeles and San Diego, have implored Bush’s Interior to proceed with caution as it races in these last days to develop mining, gas and oil near the river.

“We have other sources of power,” said Jeffrey Kightlinger, MWD’s General Manager. “We don’t have other sources of water.”

Hot Water

One of those alternative sources of energy is uranium, which is essential to the production of nuclear energy. In the last six years, new uranium mining claims within five miles of the river have nearly tripled, from 395 to 1,195, according to a review of BLM records by the Environmental Working Group, a Washington-based policy organization.

Although few of those claims will actually be mined, mining has a track record of contamination that alarms water officials dependant on the river. The Metropolitan Water District points to a 16 million ton pile of radioactive waste near Moab as a warning of what can happen when mining isn’t carefully controlled.

The pile sits on the banks of the Colorado at the site of a mill that once processed uranium for nuclear warheads. The plant closed in 1984, but the Grand Canyon Trust estimates 110,000 gallons of radioactive groundwater still seep into the river there each day. The U.S. Department of Energy decided in 2000 to move the pile away from the river. But the planning was so complicated and the cost so high — estimates top $1 billion — that the first loads of waste won’t be hauled off until next year.

The industry says the Moab case is an outdated blight from the distant past.

“What gets my ire up is when we get compared to stuff that happened in the 60s. There is no argument from us now about being careful… with an eye to preserving the environment,” said Peter Farmer, CEO of Denison Mines, a Canadian company that operates seven U.S. mines as well as the nation’s only operating uranium mill in Blanding, Utah.

Denison recently spent more than $5 million to triple-line a waste pit and outfit it with leak detection sensors. It’s cheaper to pay up front, Farmer says, than to clean up later.

Roger Haskins, a specialist in mining law at the BLM, agrees that concerns over mining are overblown. He says landmark environmental regulations in the 1970s prepared the industry for the 21st century. While it’s still easy to stake a mining claim, projects must now undergo extensive environmental review before they can be turned into mines.

“Whatever happens out there is thoroughly manageable in today’s regulatory environment,” Haskins said.

Scientists say some degree of pollution is inevitable, because mining sometimes uses toxic chemicals like cyanide. It also exposes naturally toxic metals that would otherwise remain deep underground.

Drilling for uranium creates pathways where raw, radioactive material can migrate into underground aquifers that drain into the river. Surface water can seep into the drill holes and mine shafts, picking up traces of uranium and then percolating into underground water sources. The milling process itself creates six pounds of radioactive and toxic waste — including ammonia, arsenic, lead and mercury — for every ounce of uranium produced.

“There has to be some impact to downstream water. Whether or not we can measure — that is the question,” said David Naftz, a hydrologist at the U.S. Geological Survey in Salt Lake City who studies uranium mining.

Naftz has documented dangerous levels of uranium near waste dumps at more than 50 separate test sites in Utah. While much of the mining happens in high, dry places where contaminants don’t easily seep into surface water, he says periodic storms can still wash them into the river.

“What we’ve done is kind of upset the geochemical equilibriums in these basins by taking these ores and exposing them to conditions on the surface,” he said. “The question is, how long is it going to take to transport them down to water systems?”

Pollution problems with gold, copper and other mines also challenge the assertion that technology and better regulation have eliminated the environmental risks.

One study compared the EPA’s environmental impact statements for 25 sites to what really happened after mining took place. Water at three quarters of the mines was found to be contaminated, even though the mines used technology and techniques that the EPA had said would keep the environment clean, according to the research done for the Earthworks by Jim Kuipers, an environmental engineer in Butte, Mont. and Ann Maest in Boulder, Colo.

At least four large mines that operated as recently as the 1990s — long after new regulatory standards were put in place — have caused so much contamination that the EPA designated them as priority Superfund cleanup sites. One rendered a 20-mile stretch of a Colorado River tributary completely dead.

“Promises are made and promises are broken,” said Roger Clark, who is director of the Grand Canyon Trust’s air and energy program and has been monitoring the rise in mining claims near the Grand Canyon. “This is not something we can sit back and take industry’s word for.”

Clark, who explored the Colorado River as a Boy Scout and later as a river guide, already has seen signs of the park’s decline. On a recent hike along the Grand Canyon’s rim, he passed a stream whose water he drank freely as a boy. Now it’s marked with a sign saying, “Drinking and bathing in these waters is not advisable.” The Park Service posted the same warning along five other canyon streams that feed into the Colorado, because high concentrations of uranium have leached into the water, likely from old mines.

In June, the House Natural Resources Committee invoked a rarely-used authority to force the Bush administration to make one million acres of public land adjacent to the park ineligible for exploration. Two months later, though, Interior Secretary Dirk Kempthorne allowed some 20 new claims in the area by deciding that the committee’s move violated executive authority.

Secret Chemicals

In the last decade, a pattern of contamination has also emerged in places where natural gas drilling has intensified. If drilling increases substantially across Colorado, Wyoming and Utah, it could also imperil the river.

Most wells rely on a process called hydraulic fracturing, which requires as much as two million gallons of water plus small amounts of often-toxic chemicals for a single well. The waste water then sits in open pits until it is treated, recycled or disposed of.

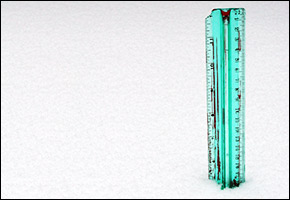

In February a waste pit high on a mesa overlooking the town of Parachute, Colo. sprang a leak, allowing some 1.6 million gallons of fluid to soak into the arid earth. According to state records, the spill migrated underground until it seeped from a cliff side and froze into a gray pillar of ice more than 200 feet tall. When it melted, the fluids dripped into the torrid currents of Parachute Creek and finally dumped into the Colorado River.

Although the number of gas drilling accidents in the upper Colorado River watershed is small relative to the amount of drilling, they have begun adding up. Colorado state records show that of some 1,500 spills in drilling areas since 2003, more than 300 have seeped into water. In one case last summer a truck carrying drilling fluids crashed into the Colorado, where it remained partially submerged for more than three weeks.

In neighboring Wyoming, the BLM found a 28-mile-long plume of benzene contamination in an aquifer beneath a gigantic gas field. The aquifer is near a tributary to the Green River, which in turn flows into the Colorado.

Doug Hock, a spokesman for the Canadian gas company Encana, which drills in Colorado and Wyoming, says that while there will always be spills, the fears of pollution are exaggerated. Encana uses steel and concrete casing around its drill pipes, lines its waste pits and, increasingly, cleans its waste water and re-uses it inside its wells.

“We have put in place safeguards to protect the water,” Hock said. “There is always a balance — this country has a great demand for energy.”

But because the energy industry has been exempted from so many federal environmental regulations during the Bush administration, it’s difficult to assess the industry’s true impact on the river.

The mix of chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing is held as proprietary competitive information by the industry and kept secret from even the EPA. Scientists say that without knowing the specific ingredients in the mix, they don’t know what compounds to test for after a spill and can’t check to see if they’ve reached the river.

The 2005 Energy Policy Act exempted hydraulic fracturing from the Safe Drinking Water Act. Also exempted from federal control and water protection laws are the drilling industry’s construction activities, including the sediments and dust produced from thousands of miles of road building, site grading and the drilling itself, even though that debris often ends up in waterways.

“We have seen an explosion in drilling, and at the same time we have seen a weakening of the federal standards under which drilling occurs,” said Dusty Horwitt, an analyst with the Environmental Working Group.

Given the relaxation in regulatory authority, the development may be out-pacing scientists’ ability to measure the implications.

In August drilling companies bid on 55,000 acres of federal parcels atop the Roan Plateau, a cherished wilderness area in central Colorado that drains into the Colorado River. A September report from the University of Colorado Denver predicted that in 15 years Garfield County, a western drilling area bisected by the river, will have 23,000 wells, six times what is has now, based on permit applications already filed with the state.

The push to drill continued last week, when the BLM opened 148,598 more acres of federal land near Moab to drilling. Quarterly lease sales in that area during the last two years were typically about 75,000 acres.

“It seems reckless,” said Bill Hedden, director of the Grand Canyon Trust. Near his home outside Moab, natural gas drilling rigs may soon be visible through Delicate Arch, the wind-hewn bridge of rock at Arches National Park that graces Utah’s license plate.

“We Americans have tried to export a lot of our problems off to the boondocks — but in this case the boondocks is the watershed and the problem is coming right back to us,” Hedden said.

According to Spisak, the BLM official in charge of drilling, the Maob sale is the result of “pent up build-up” in the cue of requests the agency is handling. Companies that want to drill on federal land ask the BLM to consider listing that land for a future lease sale. Over the past few years, Spisak said, environmental organizations have challenged some of the listings the BLM approved, delaying their sale. Now the agency is catching up.

“We are required to push them forward,” Spisak said. “It’s due to pressures of prices and industry, and we are responding to the market demand.”

An Unprecedented Demand

No project poses a greater threat to the Colorado River — or better represents the choice between water and energy — than mining for oil shale.

In mid November the BLM quietly approved a rule change that paved the way for extracting oil from rock deposits in Colorado and Utah, smack in the heart of the river’s watershed. If the vast deposits are mined to their potential — and it could be a decade before any of the projects go forward — the reserves could help the United States make a significant leap towards energy independence.

Getting oil from the shale, if researchers can find a reliable way to do it on a large scale, would be astronomically expensive. It might also require more water than the Colorado River can provide.

A recent study for the state of Colorado estimates that if the oil shale industry takes off in northwest Colorado, the region’s energy industry will need at least 15 times as much water as it uses now. In 30 years, the report predicts, the energy industry in the upper Colorado River basin would stop the river’s entire flow for nearly six weeks if it used the water all at once.

“It would take every bit of water rights that we currently have plus more,” said Scott Ruppe, general manager of Uintah Water Conservancy District in northeastern Utah.

Counties across the Western states are apportioned a limited quota of water rights that can be used for industry, farming, or municipal use, he explained. Using Colorado River water for oil shale means less water for urban growth, agriculture and personal use. It means trading fresh fruit and vegetables – not to mention green lawns — for energy.

“It just comes down to how needy the nation is for energy,” he said. “If energy is short then some of the other concerns might get pushed aside.”

These stark choices have driven Congress to begin examining the water problem in the absence of leadership from the White House. One of the bills that has been written would, if passed, direct the Interior Department to undertake the kind of comprehensive inventory of the nation’s water quality and supply that critics say is missing.

It will be up to the Obama administration, though, to ultimately decide the nation’s priorities. The appointment of Colorado Sen. Ken Salazar to head the Interior Department will inject a unique understanding of western water issues into Washington politics. Salazar is a long-time rancher and a former water attorney.

The new administration could temper some of Bush’s decisions by limiting mining claims in sensitive areas, refusing to finalize leases sales that haven’t been signed, and rigorously enforcing existing environmental regulations. It also could try to reverse some of the rules the Bush administration has issued to speed development, although that will be difficult.

Obama’s greatest opportunity to address the conflict between water and energy may lie not in undoing policies from the past, but in looking to the future.

“The administration has an opportunity to start thinking about water as a national resource,” said Nevada’s Mulroy. “We have no rear view mirrors anymore.”

Correction: This post originally stated that the Bureau of Land Management had auctioned off 359,000 acres of land for natural gas drilling near Moab Utah. In fact, as a result of protests over that lease sale, the BLM made a last minute change to the total amount and auctioned 148,598 acres of land on Dec. 19, 2008. This story also refers to a study comparing real pollution at 25 mines to that anticipated by the EPA. That study was commissioned by Earthworks, not the Environmental Working Group, and was authored by James Kuipers and Ann Maest.

This report comes to Circle of Blue from ProPublica, an independent, non-profit newsroom based in Manhattan that produces investigative journalism in the public interest.

Circle of Blue provides relevant, reliable, and actionable on-the-ground information about the world’s resource crises.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!