Utah mining corporation indicted for water pollution

Discharging selenium into watersheds remains a major problem in the American West

by Sarah Haughn

Circle of Blue

Mining mogul Johnson Matthey, Inc. is pleading guilty to allegations that it conspired to cover up illegally high levels of the toxic mineral selenium in the industrial run-off of its silver and gold refining plant in Utah. The plant — operating in Salt Lake City since 1932 — refines precious metals. The wastewater produced during the refinement process requires intensive treatment in order to dispose of accumulated elements, like selenium. Selenium neighbors arsenic on the periodic table and is toxic when ingested in high concentrations.

“Trace amounts of this element are necessary for healthy functioning. However, these amounts are so small that it does not take much pollution to cause problems. In humans over-exposure can cause irritability, fingernail and hair loss, and eventually internal problems and cancer risks,” says John Hart, Communications Manager for the Greater Yellowstone Coalition — an organization that provided policy expertise for a recent selenium contamination report by former U.S. Geological Survey scientist Edgar Imhoff.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), under the auspices of the Clean Water Act, monitors industrial run-off, ensuring selenium levels remain negligible. According to the U.S. Department of Justice (USDOJ), auditors from the EPA noticed that the Johnson Matthey corporation — experiencing difficulty keeping the toxic element content low — submitted measures that misrepresented the plant’s actual selenium discharge. Despite the auditors’ warnings, the plant continued to submit samples with uncharacteristically low selenium levels.

Bill Burton, an engineer at the corporation’s Salt Lake City refining plant, told Circle of Blue that the doré — unrefined gold and silver — they receive contains high concentrations of many elements. He indicated that the plant has been in compliance with their wastewater discharge permit since the selenium incident in 2001, however he declined to explain the processes used to regulate the levels of selenium discharged.

Johnson Matthey’s felony violation of the Clean Water Act means that it faces a $3 million fine. Both Utah plant managers directly involved must spend a year on unsupervised probation, and also pay fines of up to $1000 for their deceptions. Sentencing takes place in early December. Johnson Matthey posts revenues of more than $4.7 billion annually.

Dr. Dennis Lemly, a research biologist for the USDA-Forest Service who has also done extensive work on selenium pollution, believes the court’s decision “may have been a hollow victory for the prosecution. I applaud them for the attempt, but I doubt if it will have a far-reaching or lasting impact on the mining industry. It will likely be business as usual, particularly if probation, $1000 fine, and community service is all that’s coming to them.”

Selenium: An element with a past

Selenium pollution has a long and controversial history in the American West. In the 1980s, scientists working for the USGS, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS), and the Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) discovered that agricultural run-off flowing into the Kesterson Reservoir from California’s San Joaquin Valley contained toxic levels of selenium.

Originally vitalized with fresh water, the reservoir consisted of six ponds that supported ecosystems rich with fish and birds. As fresh water inflow dwindled due to limited funding and environmental concern, the government agencies introduced agricultural drainage as a supplement.

The drainage, tainted with pesticides and saturated with salts, greatly affected species dependent on the water bodies. Scientists soon observed significant changes. Of the many fish species that thrived in the ponds, only the salt-tolerant mosquitofish remained. Algae blooms — a sign of high nitrogen content — proliferated. The flora around the ponds began to die off, and birds ceased visiting the ponds.

After a study of several similar sites, the USFWS determined that the selenium content in the Kesterson Reservoir was responsible for the water pollution, causing deaths and deformities of thousands of fish and waterfowl. In 1987, officials declared the site a toxic waste dump.

“For ecosystems, the cumulative effects can be devastating. This is due to the fact that selenium bioaccumulates. This means it continues building up in an ecosystem and does not dissipate over time,” Hart says. “It also increases in concentrations as it moves up a food chain. Over time the continual build up of concentrations leads to ever worsening environmental risks. Kesterson was a perfect example of this.”

Research unveils a common problem

Following the Kesterson crisis, further reconnaissance research found over 80 percent of the areas studied in the American West also suffered from a poisonous accumulation of selenium.

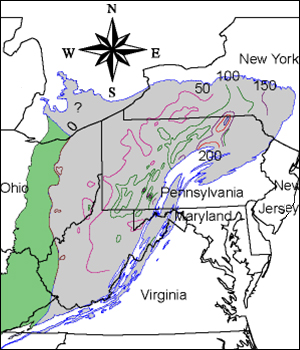

Just one year ago, retired USGS scientist Edgar Imhoff published a report documenting extensive and covert selenium pollution by Idaho’s phosphate mining industry. Imhoff cited collusion between federal agencies and the industry to coverup decades of contamination.

Imhoff wrote that “both the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality (IDEQ) identified potential selenium contamination at the Smoky Canyon Mine as a significant concern as early as 1982.” Despite the EPA’s designation of J.R. Simplot Smoky Canyon Mine as a Superfund site — a site containing uncontrolled hazardous waste — Simplot continued to seek expansion in 2007.

The government granted Simplot permission to expand this July. Residents Pete and Judy Riede, whose land is within a mile of Simplot’s proposed mining operation, are appealing the decision. “We have three major sources of water on our property,” Pete explains. “According to the Environmental Impact Assessment, all three of those major water sources will be subject to selenium contamination.”

The Riedes said that until about a year ago, few people in their community were aware that the EPA had declared the Simplot Mine a Superfund site due in large part to the high concentrations of selenium. Because the region is fairly wet and has a complex watershed, the Riedes fear the long term effects of the pollution as it works its way through the rivers and creeks.

One of the water sources near the Simplot mine, called Sage Creek, runs through property belonging to Pete and Judy’s neighbors. “He has little kids. He can’t let any of those kids ever eat a fish out of there. It’s just too risky, because they do have high selenium content,” Judy said.

The selenium seeping out of waste dumps in southeast Idaho caused the death of area livestock, as well as the pollution of groundwater. According to Imhoff’s report, “Hunters have been warned not to eat elk liver from the area where mining occurs, and parents have been advised to limit the amount of fish their children eat from one creek polluted by selenium from an upstream mine.”

Hart points out that mines have been reluctant to regulate selenium discharge. “It has proven very difficult and costly for the mining industry here in Idaho to contain the selenium contamination,” he notes. “In fact the Idaho Mining Association is in the middle of its second major attempt to change the state groundwater rule to allow for greater exemptions to water quality standards and thus be free to increase contamination under and around all mining operations.

“Their first attempt was stopped in our legislature this past spring by concerned citizens and conservation groups. They have spent much time and money on lobbying efforts and have many political assets in place.”

Is the Clean Water Act enough?

Cases like Simplot in Idaho and Johnson Matthey, Inc. in Utah continue to plague watersheds, wildlife, and human communities despite EPA regulations and monitoring efforts. The EPA explains that the Clean Water Act, put into place in 1972, initially “focused on regulating discharges from traditional ‘point source’ facilities, such as municipal sewage plants and industrial facilities, with little attention paid to runoff from streets, construction sites, farms, and other “wet-weather” sources.”

According to Lemly, the upshot of the USDOJ’s conviction is that it “positions the Clean Water Act and EPA in a better light, that is, the enforcement of CWA through EPA regulations is not to be taken lightly, and penalties can, and will be served.” But he notes that “it also exposes weaknesses in EPA’s self-monitoring approach for industry. Without adequate oversight, more JMI’s are assured in the future.”

The USDOJ’s indictment of Johnson Matthey, Inc. for illegal coverup of selenium water pollution in Utah makes the connection between on-site pollution and the deterioration of ecosystems. The conviction demonstrates that the Act still plays a role in reducing the release of hazardous waste into the country’s rivers and streams. Whether that role is significant enough to ensure the health and safety of watersheds for future generations remains unknown.

“[Selenium contamination] might not impact our lifetime,” recognize the Riedes, “but we bought this property hoping to leave it better than we got it.”

J.R. Simplot was not available for immediate comment.

Sarah Haughn is a Circle of Blue staff writer and researcher. Reach her at circleofblue.org/contact. All photos courtesy of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!