Rose George’s World of Human Waste and Why It Matters

What we should do about the dirty world of a dirty word

by C.T. Pope

Circle of Blue

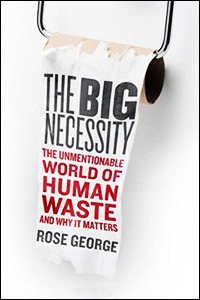

Rose George has squatted, sat, and defecated on just about every continent on the planet. She has gone in the slums of Dar es Salaam. She has used some of the most advanced Japanese toilets. She has pondered over which of the many clean W.C.s to use in the British Library of central London. And she has written it all down — excluding some of the personal details — in her new book: The Big Necessity: The Unmentionable World of Human Waste and Why It Matters.

To gain perspective on the scale and scope on the global sanitation problem, George peppers the book with some by-the-numbers facts. The most expensive toilet ever made: $23.4 million dollars. The average weight of human feces: 250 grams (8.8 ounces). The average distance between the front of a toilet seat and a male anus: 28 cm (10.5 in). The amount of untreated human waste that finds its way into oceans, rivers, and lakes: 90 percent. The number of people without any form of a toilet: 2.6 billion. The average number of people — mostly children — that die every year from “sanitation” related diseases: 2.2 million or about one every 15 seconds.

Her point: There’s an unspeakable storm brewing. And it has to do with the unmentionable.

George’s approach to exploring the world of human feces is peripatetic and rich with anecdotes. Traveling through time and space, we learn about the history of the sewers of London and New York. London’s are some 150 years old. They were built in response to rising health concerns and festering olfactory offenses. During the “great stink” of 1858, a period of drought left the Thames a tepid, brown, smelly mess, prompting action. The sewers worked. But with time and an ever growing population even these mammoth systems are starting to fail. For example, New York’s sewer system, which mixes rainwater and human waste, dumps some 500 million gallons of untreated sewage and rainwater into the Hudson or East Bay about once a week.

From the sewers of New York and London we go to Japan, to test the whiz-bang contraptions of modern bidets. The toilet manufacture TOTO used clever advertising to turn a “dry” stick wiping culture, into a modern “wet” one, in less than a century. And for those of us in “dry” cultures, that shun wet ways of wiping, George shares some fun facts. The average British male bottom is covered with fecal contamination from morning to night, whereas Japanese bottoms are considerably cleaner. She compares wiping alone to trying to shower with only a towel — the lesson is, with no water, you can’t get clean.

From there, the problems get larger and the stakes greater. The chapter “2.6 billion” begins the narrative of the sanitation crisis. The problem, according to George, runs the gamut: education, funding, understanding, culture, linguistics, and the list goes on.

To start, there is the way we talk about feces. The language of sanitation — in any culture — is euphemistic.

In English, there is a long history of the words describing what we do, and where we do it. The French word toilette was borrowed, then corrupted, and then itself euphemized away. First it was a cloth on a dressing table, then the dressing room itself, then the articles used for dressing, then any place that dressing and washing takes place, then a place for “neither washing nor dressing”, and finally the almost technical name for the device used to dispose of human waste.

Today, Americans, at least, barely “go to the toilet”. They “go to the restroom”, the “bathroom”, the “little girl’s room”. The British go to the “loo” — another French corruption. The euphemisms can be cryptic or even completely inexplicable — “going to see a man about a dog” anyone?

This aversion to the topic of feces is a big part of the problem, George explains. Mohandas K. Gandhi was one of the first public figures to openly discuss defecation and the handling of human waste in India. Imploring the upper castes to clean their own toilets, he rejected the injustices in the caste system.

In India, at the turn of the last century, the majority of fecal cleanup was done by the “untouchables”. They were a subcaste of the bhangi, or the “broken”, “trash” caste. Today they are called the Dalits or the “oppressed” caste, but they still exist and fill their sanitation roles — though in waning numbers.

Even now, in rural cities, and in some modern municipalities, the untouchables clean up the streets and toilets of India, picking up feces — often with their hands — to be carried off and disposed of someplace else. They are mostly women or young girls. They clean the toilets of the upper castes, who then deny them water to clean their hands. Diarrhea and stomach sickness are weekly events for them. They are but one story in the global sanitation crisis.

George goes on to recount others. But, at the heart of her message always is poor sanitation kills. Cholera and typhoid, two diseases that most Westerns don’t give a second thought to, are as big a problem as AIDS, malaria, or TB. But sanitation isn’t sexy. There are no celebrities lining up to stand in front of a brand new latrine in Africa or India. The global water crisis, an epidemic in and of itself, has Matt Damon. Poverty, malaria, and AIDS in Africa all have Bono and Geldof. Sanitation has its unsung heroes: Jack Sim, Joseph Bazalgette, Ronnie Kasrils, but there are no celebrities — save perhaps George herself.

Informative, witty, often wry, and undeniably important, George’s book is must a read for anyone that has every used a toilet, bush, or river to — you know — go.

Talking Sanitation with Rose George

Circle of Blue was able to talk with George about her new book and the global sanitation crisis. What follows are highlights from that interview.

Why sanitation and why now?

The reason that it’s particularly important at the moment — not just at the moment but increasingly important — is that dreadful figure of 2.6 billion people without a toilet or any form of sanitation, which is obviously just a disgraceful figure. And a child dying of diarrhea every fifteen seconds — these are just really horrific statistics. But yet, when you look at other really bad public health issues like malaria or HIV they do get a lot of political attention and funding; whereas sanitation still is sort of the neglected orphan of the development world.

What sort of aid is there for sanitation related issues?

If you know about fresh water you know that it’ll only get about one percent of the national budget anyway and most of that — 90 percent of that — will go on clean water and ten percent on sanitation, which just doesn’t make sense when you look at the public health benefits of sanitation. A good latrine or some good form of containment can cut disease by 40 percent. Four, zero. Whereas clean water is 20 percent.

What do you think is the biggest obstacle toward achieving sanitation goals?

I think the big issue there is that there is a linguistic taboo. It’s not considered a polite subject of conversation. This sort of spreads across the board. People — in terms of staffing and talent and stuff — the best people don’t want to work in sanitation; they want to work in water. It’s just got more cache.

The other issue is — and this is true in governments and the aid world — sanitation is like a political football. No one department has responsibility for it, so it gets kicked around. It’s going to be local government or it’s going to be health, or it’s going to be forestry and water affairs. I think at the moment 23 agencies in the UN have responsibility for sanitation. There’s a UN Water, but there’s no UN Sanitation, despite the appalling battle associated with it.

A linguistic taboo?

Look at euphemisms. The last time we probably used a word that actually described the receptacle we need to dispose of our human waste, was probably in the 16th century when Henry the VIII

How important is education and awareness to the sanitation problem?

Well, I think increasingly that the new trend in sanitation is the awareness that hygiene education is fundamental. You can’t just give someone a toilet and expect them to wash their hands properly.

That is happening with this movement called CLTS (Community Led Total Sanitation), which I wrote about in the book. And that’s revolutionary. Principally, it does away with the concept of subsidy. That’s the ideal methodology, anyway. Subsidy is not important, whereas before it always was. And instead the idea is to trigger people to help themselves.

They turn up in a village and have a tour of the village and then ask to be shown the open defecation grounds. Suddenly they’re standing in front of guests in front of a pile of shit, frankly. The idea is to trigger them into some sense of shame and disgust and then they will immediately dig latrines. And it seems to be working.

Are there any big issues you’d like to mention?

Well, seeing as you’re clean water people, I think another issue is that clean water gets much of the attention and you have a lot of celebrities who are willing to talk about clean water, which is great and I’m certainly not knocking that or the efforts of people working on clean water. Obviously that problem hasn’t been solved yet and is going to get worse before it gets better. But I do wish that someone would be willing to pose in front of a nice shiny latrine in a school somewhere in Africa, rather than just standing in front of a nice shiny tap.

C. T. Pope is a Circle of Blue writer and researcher. Reach him at circleofblue.org/contact.

Circle of Blue’s east coast correspondent based in New York. He specializes on water conflict and the water-food-energy nexus. He previously worked as a political risk analyst covering equatorial Africa’s energy sector, and sustainable development in sub-Saharan Africa. Contact: Cody.Pope@circleofblue.org

How do you get people here in the U.S. to get off your land and stop having B.M,s and voiding all over your property. In some cases in 5 gal. buckets. Is there some kind of rules in the U.S. (Tennessee) about that and what is the required clean up for the mess? Please help and thank you in advance for your help.